Elizabeth Stirling

and the Musical Life of Female Organists in Nineteenth-Century England

Using the life and works of Elizabeth Stirling as a case study, this book focuses on the three roles common to female organists in nineteenth-century England: recitalist, church musician, and composer.

Many rich and diverse primary sources are used to piece together a coherent picture of Stirling in each of these pursuits, as well as to present vignettes from the lives of her female colleagues.

The pattern that emerges is one of both overt and covert discrimination against “lady organists” in the press, rooted in beliefs held about the proper role of women in society and of music in women’s lives.

Buy the Book

The book currently is out of print but may be found in libraries and purchased from used book sellers:

Chapter 2

‘Ladies Not Eligible’?

Women who sought work as church musicians in nineteenth-century England faced a number of issues raised by churches that refused to consider them for employment and by men intent on maintaining the current social and economic status quo. In general, ladies were more successful at gaining access to the organ bench than to the choir stalls, which were closed to them on musical and religious grounds as well.

‘Come all my brave Boys’

The opening lines of Samuel Wesley’s musical spoof on the process of organist elections in England at the end of the eighteenth century had more than a grain of truth to them in the nineteenth century. ‘Come all my brave Boys who want Organists’ Places’, he wrote, ‘I’ll tell you the Fun of the Thing.’1 Wesley had firsthand experience with the selection of church organists. He had applied unsuccessfully in 1798 for the organist post at London’s Foundling Hospital Chapel won by John Immyns. Wesley’s music commemorates the event, which was in his words ‘a Bamboozle’.2

Wesley’s text alludes to questionable practices involved in the selection of a church organist. Officials might feign good intentions, but the result was a biased election. An obvious case was when some churches in nineteenth-century England declared ‘ladies not eligible’ to apply for vacant organist posts. Before examining this pattern of overt and covert discrimination against female organists, it is helpful to review how church organists were chosen and to identify some of the shortcomings of the selection process documented in the nineteenth-century press.

A church’s procedure for choosing an organist typically involved the following steps: seek applications from interested organists; choose some of the applicants to audition; select final candidates from among these organists; and elect one of the finalists to the position. But the procedure was not infallible. For example, congregations entrusted as judges were apt to be carried away by a showy player ‘who treated them to a “tootle” on the flute stop, or a flimsy “tittup” on the trumpet or cremona’, or by a brilliant player who could ‘produce the maximum number of pedal and manual notes in the minimum number of seconds’.3 Neither, however, was necessarily the best organist for the post. Likewise, church personnel were occasionally swayed by nonmusical factors in their choice of an organist.

In an effort to rectify the situation, nineteenth-century music journals printed letters and editorials exposing perceived faults in this trial by skill method of choosing an organist and suggesting remedial action. Selection of an organist by a parish vestry without counsel of a musical judge was troubling to some writers, but even more disconcerting was when a vestry disregarded the recommendation of a musical judge. When in 1880 St Sepulchre, Holborn, reversed the decision of John Stainer, the musician brought in to judge the organist election, the Musical Standard took the church to task:

With regard to the Vestry, the less said the better. They have only afforded yet another reason why organs should not be disposed of by competition, and have only helped to hasten the time when musicians of note will decline to officiate as umpires, and players of ability refuse to be trotted out for the delectation of ignorant and bumptious vestrymen.4

Declaring emphatically in 1883 that the competitive trial was decidedly the worst method to choose an organist for a church, the Musical Times admitted that the method might be acceptable in the case of

a very young man, who has had previously no opportunity of showing his power otherwise; but then let it be understood that the post is one for which a decidedly young man is wanted, and let there be no objection to a gentleman even in the trammels of his teens.5

The journal’s repeated reference to a male organist was not an oversight. Eighty-five years after Wesley’s invitation to ‘all my brave Boys’ to learn the fun of securing an organist position, the organ loft was still considered man’s domain, and women who aspired to occupy the organ bench were encroaching on male territory. Throughout the nineteenth century, churches found ways to discourage this unwanted incursion.

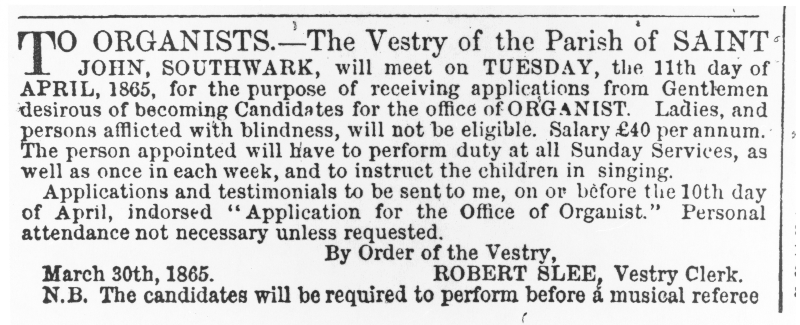

On 8 April 1865 the Musical Standard carried an advertisement by the vestry of St John, Southwark, shown in Figure 2.1, inviting ‘applications from Gentlemen desirous of becoming CANDIDATES for the office of ORGANIST. Ladies, and persons afflicted with blindness, will not be eligible’.6 The linking of ladies with blind persons may have alluded to incapacities in women comparable to infirmities that, in the mind of an 1862 contributor to the same journal, entitled the blind to compassion and assistance, but not to a position in which they might ‘do infinite harm, by rendering the musical portion of harm, by rendering the musical portion of our public worship uninteresting, if not ridiculous’.7

Figure 2.1 Advertisement for organist for St John, Southwark, Musical Standard, 1865

In fact, the wording of the advertisement ostensibly was intended to prevent physical harm to female organists who might have applied for the position, since Mr Bradford, a vestry member, ‘had heard it from a professional man, that it was absolutely injurious to the health of a female to play the organ at St. John’s’.8 The true motive remains suspect, however, given that the most recently resigned organist was female. Kate Davis had been chosen the church’s organist from five candidates on 15 September 1863 in what may have been a tainted victory: The Musical Standard considered the election a farce marked by indignities that prevented talented men from applying for the post.9 On 1 April 1865 a letter was read from Davis at a St John vestry meeting, ‘resigning her position as organist of the parish church, and thanking the rector and churchwardens for the kindness they had shown her during the time she held office’.10 A week later the advertisement for a new organist appeared in the Musical Standard.

The decision of the St John vestry in 1865 was not an isolated case but rather evidence of ongoing discrimination against female organists in some of England’s churches. In 1853 Punch had addressed the issue when it asked whether St Cecilia, the patron saint of organists, would be eligible for the recently vacated organist post at St Helen, Bishopsgate. The advertisement to which Punch referred was gender neutral in its wording, but Mr Punch had heard ‘that it is the practice of many vestries to exclude female candidates from competition for the organist’s office’ and wanted to spare Cecilia ‘the anxiety and trouble of making an application, in doubt whether or not it has been predestined to be fruitless’. Punch continued: ‘One would think that the church of a female saint would admit a female musician—or can it be that ST. HELEN would have closed her doors against her sainted sister, the namesake of Miss Punch, herself?’ In a more serious vein, Punch concluded: ‘To multiply, not to diminish, the means of honourable maintenance for women ought to be the object of all Churchwardens and Vestries; as it certainly is the interest of all rate payers.’11

An 1854 advertisement to fill the vacant organist position in the parish church of West Hackney with its ‘Ladies not eligible’ stipulation confirmed what Punch suspected. Recalling the advertisement six years later, in 1860 an indignant correspondent to the Musical World decried the ‘unmerited and unmanly insult’ that still treated women as ‘inferior beings’. His charge to popular writers nobly to employ their pens ‘in checking the progress of this increasing public evil’ apparently went unheeded.12 The pens of other writers were not idle on the matter, however, as seen in a flurry of letters to the Musical World in 1857 and the Musical Standard in 1863 debating the issue on points of social propriety, physical strength and musical skill.

‘No lady need apply’

Questioning the ‘No lady need apply’ appendage to some advertisements for parish organists, A Clergyman writing to the Musical World in 1857 asked, ‘Why should a really competent female be set aside (as is often the case, to my own knowledge) for the sake of a less competent male, simply because she is female?’ He cited several highly gifted organists, among them Ann Mounsey Bartholomew, Elizabeth Mounsey, Elizabeth Stirling and Miss Cooper, as evidence that women could play the organ and conduct choirs as well as their male colleagues.13 One of two correspondents taking Oboe as a pen name thought he had the answer, having once visited a female organist in the loft during a service: ‘Do you, Sir, think that it is a decent or proper profession for a lady to follow?’ In answer, the other Oboe raised his own point of propriety: ‘What business had this “gentleman” in the organ-loft during the service? Organists, when they visit a strange church, never rest until they have made their way into the organ-loft, there to tease and torment the unfortunate inmate.’14

A Lady Organist who joined the discussion shifted the focus from sex to skill, asking ‘How does “Oboe” account for the fact, that almost always where ladies are nominated with gentlemen to compete for appointments, and have played before professional umpires, they have been returned by them as competent to hold the office.’15 As evidence she invited Oboe to observe her in the organ loft during a service, ‘where he would hear an efficient choir, commenced and carried out entirely under my own direction, to the perfect satisfaction of the clergyman and the increasing congregation’.16 Although in the view of the journal’s editor A Lady Organist had modestly and appropriately vindicated her sex, he attributed personal motives to her invitation and thus undermined the female organist’s professionalism when he mockingly warned Oboe ‘not to accept this insinuating “invite”— unless he has no disinclination to a probable case of “Mrs. Oboe”’.17

‘The organ is by no means a lady’s instrument,’ correspondent Pedal declared, explaining, ‘Their very dress is against them, since it impedes their pedaling.’18 Not only was the act of raising one’s skirt a foot or so to facilitate pedaling unbecoming and immodest, Pedal claimed, the positions necessary to play the pedals were extremely indelicate, if not indecent. ‘No female but a Bloomer should be an organist,’ he stated,19 referring to the baggy ankle-length trousers worn beneath a loose knee-length tunic made popular by American Amelia Bloomer in the 1850s. Any woman who would wear such a costume, according to Pedal, was sufficiently masculine to be an organist but, because her femininity was then suspect, had consequently lost her respectability.

A letter signed A Metropolitan Churchwarden urged a stop to the prejudice against female organists, whom he preferred because they were usually more desirous than male organists to please clergy and congregation. But setting personal bias aside, he advocated equality of opportunity for organists of either sex.20

In the issue in which the last of these letters appeared, the Musical World published a response stating that it had heard enough of these futile, at times unfair arguments, which almost assumed ‘the form of a crusade against the fair sex’. Oboe, the editor pointed out, would have shown a better sense of decorum had he joined the congregation in worship instead of visiting the organ loft, or if prayer was not his reason for attending the service, had stayed away from the church altogether. Pedal was chastised for his immodest thoughts in church concerning a lady’s exposed ankles. Even A Metropolitan Churchwarden’s preference for lady organists was considered an affront to females, who might reasonably exclaim ‘Defend us from our friends.’ The claims of correspondents such as Oboe and Pedal, the editor suggested, masked the real reason for their harangue: Organists far outnumbered churches, and by eliminating women from competition, men would have a better chance of securing organist positions.21

It was a simple matter of supply of organists exceeding demand for their services, complicated by the generally low salaries that church musicians felt compelled to accept if they wanted work. An ordinary parish organist in nineteenth-century England could expect to earn between £20 and £40 a year—approximately the wage of a well-paid servant22—though some were paid less.23 An annual salary of £50 to £60 was considered more reasonable by organists, given the number of services and choir rehearsals requiring their attendance. Poet James Hipkins couched the socio-economic situation in a humorous vein when he wrote, ‘An organist wanted—and one that can play / Seven hours in the night and seventeen in the day.’ His tongue-in-cheek parody on advertisements of the day addressed the contentious issues more cogently:

This is a first-rate chance for a first-rate organist, as the duties are light, being only three services on a Sunday, and two on every Christmas day and Good Friday, and all feast-days and fast-days throughout the year. A part of one day in every week to be devoted to teaching one hundred twenty-seven charity children the art of psalm-singing. Salary £15 per annum. A professional lady not objected to.24

That a woman might be willing to play for such a meagre salary impeded efforts to improve the situation of organists in general. But the Musical Standard did female church organists a disservice when it introduced the fictional Miss Keypounder in a scenario illustrating churches’ inability to appreciate a good musician. Faced with a male organist to whom the ‘generous’ wage of £50 per annum was considered too low, a churchwarden replied, ‘Anybody can play an organ. When we was without one before, Miss KEYPOUNDER played beautiful, and I don’t see no difference between her playin’ and the man who had fifty pound a year; I propose that Miss KEYPOUNDER be asked to take regular charge of our services.’ She gladly accepted the post at the much lower £20 per annum offered. The journal elaborated: People like the churchwarden could not distinguish between good service playing and that of the KEYPOUNDER order, whose loud playing gave the congregation plenty of noise for their money.25

Music journals periodically included exposés of organists forced to resign their posts for a number of reasons including playing in a style at odds with the musical taste of clergy and congregation; turning the service over to a deputy instead of performing all duties in person; and having the temerity to request a raise in salary. Most of these published accounts concerned male organists. Thomas Hardy, who wrote about female organists in poetry and in prose, offered a poignant account of a female organist whom the deacons dismissed when she did not live up to their high moral as well as musical standards:

I lift up my feet from the pedals; and then, while my eyes are still wet

From the symphonies born of my fingers, I do that whereon I am set,

And draw from my ‘full round bosom’ (their words; how can I help its heave?)

A bottle blue-coloured and fluted—a vinaigrette, they may conceive—

And before the choir measures my meaning, reads aught in my moves to and fro,

I drink from the phial at a draught, and they think it a pick-me-up; so.

Then I gather my books as to leave, bend over the keys as to pray.

When they come to me motionless, stooping, quick death will have whisked me away.26

Dismissals may not have had such tragic results in actual Victorian life, but they could be devastating to women who may have relied on an organist position to support themselves financially. In 1860 the Musical World published a statement on request concerning the unwarranted dismissal of an anonymous female organist at a well-attended district church who ‘made respectful application to the incumbent and the churchwardens for an increase of salary’. A talented organist of good reputation, with several musical compositions to her credit, the woman had held her current position for four years, during which time she had, by the journal’s account, been the victim of ‘much mortification, unusual interference, and harsh treatment’. Her duties, for which she was paid £20 a year, entailed over 200 attendances annually in addition to rehearsing the choir and instructing the children. The Musical World lamented, ‘Twenty pounds a year, with a chance of little teaching, yields but a poor income for a lady’s maintenance; and there is much praise due to this class of under-paid for reserve and delicacy in not wishing their trials and humiliations to be paraded before the public.’27

The question of women’s competence as church organists that had been raised in letters to the Musical World in 1857 resurfaced as a theme in 1863 in the Musical Standard. Ann Mounsey Bartholomew, Miss Couves and Mrs Thomas Perry were among the very few exceptions whom correspondent Pedals—not to be confused with correspondent Pedal—was willing to admit into the priesthood of organists, but their female colleagues who had infiltrated the ranks were to blame for the low esteem with which the organist position was currently held. He offered many reasons: Female organists appeared to lack decision, vigour, self-possession and firmness necessary in organ playing. They did not use the instrument to its full extent, and they played too fast.28

Manuals, another correspondent, admitted that many female organists played badly, but many male organists played badly too. Believing that skill, not sex, should determine competency as an organist, Manuals asked, ‘What is there, either intellectually or physically to prevent ladies playing as efficiently as the opposite sex?’29 He used pedal playing as an example: Many men had to see the pedals before they could play them, but women, whose crinolines distended their skirts and concealed the pedals, played them correctly.30 Correspondent W. C. Filby put it more succinctly: ‘As to pedalling, a lady cannot look at her feet—a gentleman ought not look at his.’31 Concerning physical requirements, Filby observed that the control of an organ required no super-feminine strength. He concluded, ‘I only ask that, on the musical question, no sexual difference may be recognized; that female organists shall be neither flattered, pitied, nor despised; but that they may be tried in the exacting balance of musical exigency, and only rejected when they are found wanting.’32

Correspondent Pedals was not convinced. Women were not physically equal to the task of organ playing, he claimed. Let Filby ‘play the “Hailstone Chorus,” with swell coupled to great, on one of Hill’s large organs’, and then ask himself if female organists possess the requisite strength. ‘I doubt whether a lady would not break down from sheer exhaustion, long before the final chord,’ Pedals remarked.33 As to other sexual differences, he explained:

I deny that I object to the ladies on account of their sex … . My objections arise solely from their natural inabilities—inabilities over which they have no control, since they are inherent in their nature; and if it has not pleased the great Maker of All to endow them similarly to men, it is not their fault. But still they must not endeavour to fill appointments to which the endowments of men alone are equal.34

The debate in the Musical Standard continued with some new correspondents adding their views about the ‘lady organist’ issue. In a revealing secondary theme, D. Maskell asked Alfred Beale whether in 1858 he had on three occasions lost organist elections to ladies in competitions before professional umpires.35 Beale responded that he had played not three, but four times unsuccessfully against lady organists. One competition Beale chose not to discuss because of its disgraceful nature; another he blamed on the poor quality of the organ. In the other two auditions, Beale claimed, he was judged the best player, but the appointment in each case was given to a female candidate.36 To the numerous reasons offered in the correspondents’ letters of 1857 and 1863 why women should not be organists, Beale had unwittingly added another: male pride.

The correspondent signed A Female Organist who entered the discussion rebuked Manuals’s gallant defence of his sister organists. ‘We feminines do not want such toleration, we require no such mock homage, we do not care that the other sex should attribute to us qualities which we know we do not possess,’ she wrote. Filby put the matter in proper perspective, the female correspondent stated. He asked for fairness, which was all she and her sister musicians wanted.37

It was in part to achieve this fairness in organist elections that in 1858 the Lady Organists’ Association was formed to bring ‘more prominently before the public the position and claims of ladies qualified for situations as parochial organists, who are too much in the habit of having their applications disregarded, and their qualifications deprecated, when applying for public appointments of this kind’.38 The justification for the organization, open to organists of either sex interested in advancing public opinion of organ playing as a female occupation, was stated in the prospectus that concluded:

Few spheres of occupation seem more appropriate to the gentler sex than that of the musical profession, and it is to be believed that this association will do much to silence the paltry rivalry and clamour which is now obviously rife at most organist elections—a rivalry in great measure confined to amateurs—as well as to raise the character of female performance upon the noble instrument in question.39

Yet the policy of excluding females as applicants continued past 1880, when St Botolph, Aldgate, in the City of London pronounced ‘Ladies not eligible’ for appointment to the church organist position.40 Equally exclusionary was the wording found in far more advertisements addressed, as in the case of St Botolph Without, Aldgate, in 1866, to ‘any GENTLEMAN desirous of becoming a CANDIDATE for the organist position’.41 Capitalizing the letters of ‘gentleman’ left no doubt concerning the fate of female applicants. Similar announcements appeared as late as 1895.

The chapter continues.

Notes

- Samuel Wesley, ‘Come all my brave Boys who want Organists’ Places’, British Library, MS Add. 35005, 85r.

- Ibid., 87v; James T. Lightwood, Samuel Wesley, Musician: The Story of His Life (London: Epworth, 1937), 92; Dawe, Organists, 113–14.

- ‘Congregational Umpireship’, Musical Standard, n.s., 13 (1871): 105; ‘The post of organist’, Musical Standard, 3rd ser., 18 (1880): 73.

- ‘Organ Competitions’, Musical Standard, 3rd ser., 18 (1880): 233.

- ‘On the Selection of an Organist’, Musical Times 24 (1883): 254.

- ‘To Organists’, Musical Standard, o.s., 3 (1865): 328. St John, Southwark, was also known as St John, Horsleydown.

- ‘On Choosing an Organist’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1862): 19.

- ‘Elected Vestry of St. John’s, Horsleydown’, South London Journal, 1 April 1865.

- ‘St. John’s, Horsleydown’, Musical Standard, o.s., 2 (1863): 77.

- ‘Elected Vestry’, 1 April 1865.

- ‘Organist: A Vacancy’, The Times, 11 November 1853; ‘St. Cecilia and St. Helen’, Punch 25 (1853): 288.

- A Seat-Holder at a District Church, ‘Church Organists’, Musical World 38 (1860): 513.

- A Clergyman, ‘No Lady Need Apply’, Musical World 35 (1857): 553.

- Oboe, ‘The Ass in Lion’s Skin’, Musical World 35 (1857): 577; Oboe, ‘No Lady Need Apply’, Musical World 35 (1857): 586.

- A Lady Organist, ‘No Lady Need Apply’, Musical World 35 (1857): 586.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pedal, ‘No Lady Need Apply’, Musical World 35 (1857): 585.

- Ibid.

- A Metropolitan Churchwarden, ‘No Lady Need Apply’, Musical World 35 (1857): 585.

- ‘Really some of our organists’, Musical World 35 (1857): 588.

- Mitchell, Daily Life, 55–56.

- ‘The Pay of Organists’, Musical Standard, 4th ser., 40 (1891): 237.

- James Hipkins, ‘An Organist Wanted’, Musical World 35 (1857): 647.

- The Pay of Organists’, 237–38.

- Thomas Hardy, ‘The Chapel-Organist (A.D. 185—)’, in The Collected Poems of Thomas Hardy [1898] (New York: Macmillan, 1926), 601–2; idem, Under the Greenwood Tree or The Mellstock Quire: A Rural Painting of the Dutch School. [1872] (Macmillan: London, Melbourne and Toronto, and New York: St Martin’s Press, 1966).

- ‘Lady Organists’, Musical World 38 (1860): 560.

- Pedals, ‘Organists: The Ladies v. the Gentlemen’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 258.

- Manuals, ‘Male and Female Organists’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 274.

- Ibid., 274–75.

- W. C. [William Charles] Filby, ‘Male and Female Organists’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 274.

- Ibid.

- Pedals, ‘Pedal’s Reply’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 287.

- Ibid.

- D. Maskell, ‘Gentlemen v. Lady-Organists’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 307.

- Alfred Beale, ‘Mr. Beale: In Reply’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 323.

- A Female Organist, ‘A Lady to the Rescue!’, Musical Standard, o.s., 1 (1863): 287.

- ‘Lady Organists’ Association’, Musical World 36 (1858): 647.

- Ibid.

- ‘To Organists: Wanted’, Musical Times 21 (1880): 321. See also ‘Organist Wanted for the Parish Church of St. Olave, Southwark’, Musical Standard, o.s., 10 (1869): n.p.; ‘To Organists: The Vestry of St. Matthew, Bethnal Green’, Musical Standard, o.s., 10 (1869): n.p.; ‘Organist Wanted for the Parish Church, Bromley, Kent’, Musical Standard, n.s., 2 (1872): 380; ‘Organist and Choirmaster Wanted for George-street Congregational Church, Croydon’, Musical Standard, n.s., 13 (1877): 268; ‘Organist and Choirmaster Wanted for George-street Congregational Church, Croydon’, Musical Times 18 (1877): 554.

- ‘Organist’, Musical Standard, o.s., 5 (1866): 342.

“What a fascinating book this is! Elizabeth Stirling was one of a very small number of female organists in nineteenth-century England who ‘made it’ (to a certain extent) at a professional level in an environment not only dominated by male organists, but also in a world almost wholly antipathetic to women doing anything other than keep house and look pretty. … Yet Stirling somehow managed to become recitalist, church organist and composer. She was a pioneer in the performance of J.S. Bach’s organ works, and won some popularity for her own music. Barger surrounds this fascinating biographical study with an excellent study of primary sources of the time: newspaper articles; concert programmes; music reviews; job advertisements; primers; fiction, and much, much more.”

– David Baker, The Organ, [British Institute of Organ Studies], 2008

Silenced Voices: Female Choristers

in Nineteenth-Century Anglican Churches

‘Ladies Not Eligible’ applied not only to organists, but also to choir members in nineteenth-century England.

Robed female choristers in the chancel of both liturgical and non-liturgical churches are a common sight in worship services today. But women’s voices were silenced in England during the nineteenth century when some Anglican parish churches dismissed female choir members in favor of boy trebles. It is tempting to interpret the reintroduction of female voices into Anglican church choirs late in the nineteenth century as a positive stride in the equality of the sexes within the walls of the patriarchal church. But in reality the act was less conclusive. Not only vocal timbre, but also church architecture, ecclesiastical policy and social convention influenced church authorities’ decision to include or exclude women as choir members.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, women were highly visible in Anglican parish church choirs. Most Anglican churches in England had been designed or modified to include a west gallery to accommodate choir and organ. According to Cambridge scholar and ecclesiologist John Mason Neale, nine-tenths of all churches in the kingdom had these raised lofts at the back of the church, where the choir was seated during services.1 The elevation of the choir, both literally and figuratively, disturbed Neale, who sounded a note of admonition:

Removed too great distance from the clergyman’s eye, having a separate entrance to their seats, possessed of strong esprit de corps, and feeling or thinking themselves indispensable to the performance of a certain part of public worship, and too often, alas! privileged to decide what that part shall be, – what wonder, if they generally acquire those feelings of independence and pride, which make the singers some of the worst members of the parish.2

Such radicalism in singers was notorious, claimed Neale, who singled out female choir members to emphasize his point: ‘And where women singers are allowed, and part-anthems are sung, the notice which they attract from their station in front of the gallery might well enough befit a theatre, but is highly indecorous in the House of God.3

This sense of decorum was the topic of The Singing Gallery by Lucy Lyttelton Cameron (1781–1858), a writer of widely circulated tracts and books for children and the poor in nineteenth-century England.4 The daughter of an Anglican clergyman of evangelical persuasion, around 1830 Cameron turned her focus to the improper behavior observed in young women who formed part of a parish church choir seated in the organ loft. Showy ribbons on bonnets and an excess of curls in the hair, incessant whispering and laughing with young men in the choir and a general lack of attention to and participation in the worship service were among the bad habits in need of amendment.

Although their voices were not faulted at that time, women on display in the choir were thought to detract from, not to enhance, the worship experience. Their singing was associated more with secular than sacred occasions Perhaps the sight of female choir members reminded clergy and congregation of operatic divas, of popular ballad singers or even of music hall performers – associations that had no place in the sanctuary.

During the nineteenth century, England experienced a resurgence of religious thought and practice that had implications for choir members. Begun in 1833 as a reaction of Oxford scholars to perceived governmental interference in affairs of the Church of England, what became known as the Oxford Movement found supporters in Cambridge, where scholars formed the Cambridge Camden Society in 1839 and became known by the name of their periodical publication, The Ecclesiologist.

Members of the Oxford Movement propagated their beliefs in a series of Tracts for the Times, giving the name ‘Tractarians’ to the movement and to those persons who supported its teachings. The tracts used as their starting point the article of the creed, ‘I believe in one Catholic and Apostolic Church’, the meaning of which essentially had been forgotten by a church that ‘seemed to have lost all sense of its divine origin, mission, and authority’.5 In the minds of some High Churchmen, the Anglican Church had become too ‘Protestant’, privileging the anti-Roman orthodoxy found in the Thirty-nine Articles over the older Catholic tradition found in the Book of Common Prayer.6 The tracts did not focus on church music; that topic was addressed by the Cambridge Ecclesiologists in their publications beginning in 1843.7 The influence of these two reform-minded groups of theologians eventually extended beyond the academic setting to the wider urban and rural parishes.

A goal that the Ecclesiological (previously Cambridge Camden) Society shared with the Oxford Architectural Society was the study of Gothic architecture and ecclesiastical antiquities.8 Both groups advocated and advised a return to the splendour of medieval architecture in the building, restoration, and modification of churches. Architectural reform as envisioned presented the thorny issue of accommodating choirs and organs. Since the west gallery at the back of the church sanctuary, where most choirs and organs were located, was not found in ancient churches, church leaders advocated its removal.9

The chancel, an important medieval feature often bereft of its original purpose in nineteenth-century churches of accommodating a number of resident clergy, was to be reinstated if an acceptable use could be found. The answer lay in relocating the choir from the back of the church to the front chancel. Although initially reluctant to admit laypersons into the ‘holy precincts’ of the chancel, the reformers relented in the case of lay choirs.10 The singers in the chancel were to be surpliced, that is, to wear robes, and, because the cathedral model was to be emulated, all choristers would be male. If female vocalists were a distraction in the west gallery in the rear of the church, their presence would be considered even more disruptive in the chancel near the altar, the church’s focal point.

When parish churches began to adopt the Anglican cathedral model of all-male choirs, women who were singing in the mixed choirs previously found in these churches were dismissed, and boy singers filled their places. The extent of this change can be surmised in the number of advertisements in music journals for male versus female choir members in the second half of the nineteenth century. Advertisements for male voices were at least 16 times more prevalent than those for female voices. This choral innovation met with varying degrees of success depending on the availability of boys with good voices, choir directors to train them and parish funds to support the music program. Not all churches implemented the cathedral choir model, and some parishes that did were not satisfied with the results. Boys could be hard to discipline, and their voices tended to break just at the time when they were most useful. Whether or not ladies should sing in church choirs provided the topic for a spirited debate in the press in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In 1848 a correspondent who signed himself ‘A Chorister’ aired his views in the Musical Times. Dissatisfied with the sound of boys’ voices in choirs, he suggested the use of female voices instead – if not objectionable on serious theological grounds and if a proper uniform could be provided.11 The correspondent’s request that the matter be taken up by ‘more able advocates’ among the Musical Times readership apparently came to nothing at the time. But the letter identified two major arguments used against female choristers.

As the introduction of all-male choirs spread through the parish churches over the next several decades, the exclusion of women from choirs became increasingly difficult to justify. Why should female voices that were valued in choral societies and in oratorio choruses and were heard in congregational singing be less valued in the chancel of a church? A brief exchange of letters in the Musical Times in 1886 and 1887 showed that the issue was still on the minds of some readers.

When in August 1889 a correspondent signed ‘Musicus’ asked the readers of the Daily Telegraph what objection there might be to a mixed choir of ladies and gentlemen, he received an immediate, overwhelming response. Claiming the topic ‘much ado about nothing’ – a case of making mountains out of molehills – the newspaper, which came out in favour of female choristers, printed 92 of the hundreds of letters it received daily over a two-week period.12 If this may be considered a representative sample, then supporters of female choristers outnumbered opponents about five to four, with other correspondents not stating a clear preference. Opinions were not split consistently along gender lines. For example, of those correspondents that could be identified as female, not all approved of female choristers, and male correspondents also were divided in their views. The newspaper correspondence stimulated further discussion in music journals until the topic had run its course.

Two types of arguments predominated in the press. The first, comparing women singers with boy trebles, involved a judgment call: Which group had the better voices? Which voice timbre was best suited for church music? Which group was more manageable? The second, focusing on female choristers, dealt with overlapping issues of propriety from scriptural, social and ecclesiastical perspectives: Should women be permitted to sing in church? Should they be seen in the chancel? How should they be dressed? Issues of propriety were the most contentious.

What began as a discussion of what women in the choir should wear turned into an argument about whether they should be choir members at all. Correspondent Arnold Russell dismissed the idea succinctly as ‘unworkable’, ‘unmusical’ and ‘unscriptural’. The dictum of St Paul that women should keep silent in church, found in First Corinthians (14: 34), lent support to both sides of the argument. But those correspondents more familiar with the entire verse pointed out that the injunction was against women speaking, hence preaching or prophesying, not against singing. And as the correspondent signed ‘Practically Religious’ remarked, ‘It is rather too late in the day to discover that St. Paul intended that women should take no part in singing in churches, since they have long done so, and still do, in at any rate many country churches. By all means let them.’

If a woman is permitted to enter other male professions, why not the choir as well? a male correspondent asked. ‘Beware!’ Edward Husband and other conservatives warned. Admit women into the choir stalls, and next they will want to be choir mistresses. Even the pulpit would no longer be considered off limits. That was just what Cassandra, one of the female correspondents, had in mind, though other females, such as Rose Grove who thought women should not try to fill men’s shoes, did not hold the same view. Correspondent Husband admitted that a theological objection to female choristers was groundless when a church had a female organist. To M. Kingston the idea of excluding female choir members was absurd when women played the organ in village churches. When Arthur Edwards remarked that ‘the fittest will survive, and this is true with respect to church choirs as anything else’, he was writing in favour of boy’s voices, but his truism was more a prophesy of the increasing presence of women as choir members in England’s churches.

The sight of a female chorister was more problematic than the sound of her voice for many churchgoers. What was a divine spectacle to one correspondent was repugnant and abhorrent to others. Church officials long had been concerned with the spectacle created by the mixed choir’s presence in the raised loft at the back of the church during the anthem. Women in the chancel would have the same effect as women on stage, in essence turning the choir stalls into a proscenium and the congregation into an audience for a performance less worship than concert. For some correspondents the answer lay in letting women form an auxiliary choir in the nave among the congregation, in the west gallery or in the Lady Chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The seemingly trivial matter of how female choristers should be attired took on inordinate importance in the press. In the Church of England at the time, choirs of men and boys wore a loose, tunic-like white surplice over a dark, skirted cassock. But some correspondents to the Daily Telegraph considered women ineligible to wear these garments because, using syllogistic reasoning, the cassock and surplice were the official ecclesiastical dress of the clergy, and by canon or church law women could not serve an ecclesiastical function. Therefore, women could not wear the cassock and surplice. But nor should women in the chancel attract attention dressed in their Sunday finery. Correspondents made suggestions for appropriate attire – Salvation Army dress, hospital nurse uniform, black dress and white cap. Of particular interest are the descriptions in the press of vestments worn at the time by female choristers. All were intended to provide uniformity, to harmonize with ecclesiastical surroundings and to neutralize the effect of ‘the daily caprices of fashion in feminine attire’, while preserving a woman’s femininity.13 Among vestments in use were:

- An ordinary surplice over a dark dress with a small biretta cap.14

- A pleated surplice with a violet velvet Tam O’Shanter cap – actually a D.C.L. cap worn by a Doctor of Civil Law – to match the hangings of the church.15

- A long ulster cloak of fine French grey wool, lined with red silk, and a black velvet hat, something like a college cap but not as stiff.16

- And the same cassock and surplice worn by male choristers with the addition of a mortarboard cap.17

A common denominator of female vestments was some type of cap to cover the head to comply with more words from St Paul, also from First Corinthians:

Every man praying or prophesying, having his head covered, dishonoreth his head. But every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoureth her head; for if the woman be not covered, let her also be shorn; but if it be a shame for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered. For a man indeed ought not to cover his head, forasmuch as he is the image and glory of God: but the woman is the glory of the man. (11: 4–7 KJV)

By the end of the nineteenth century, women once again had gained entrance into some of England’s Anglican church choirs, now located in the chancel, but not without some ambivalence on the part of church authorities. Whether for reasons of prejudice or of propriety, when females were reinstated, they were given a back seat to males in the choir stalls, hidden from direct view of the congregation. They took their seats before the service began, and only male choristers walked in the opening procession. Women’s voices may have been deemed acceptable, but in a notable departure from the teachings of St Paul, theirs was now an audible rather than a visible presence. Letters to the Musical Times from singer ‘Cantatrice’ and organist M.J. Cope, both female, show that at least some women supported this plan.18

Women were making notable gains in education and employment in England during the second half of the nineteenth century. Universities opened course work and examinations to them, and businesses hired female typists and clerks. But the expansion of roles for women in the church lagged behind. Although Nonconformist churches were becoming steadily more liberal in this regard, to W. Lyon Blease, writing about the emancipation of English women, the Church of England competed with the legal profession ‘for the dubious honours of conservatism’.19

Marriage and motherhood still were considered a woman’s true profession in the eyes of the church. When correspondent ‘Old Crusty’ complained that in the six years that he had charge of a mixed choir, seven of his best tenors and basses wed seven of his best sopranos and contraltos, he blamed the flirtatious behavior of the women who apparently had joined his choir for matrimonial rather than musical reasons. But another male correspondent saw no harm in it:

As for poor ‘Old Crusty’ leading his best voices to the altar, why not? Surely he did a better thing then than even to train them to sing, and I suppose they could both sing afterwards as well as before. Let them all do likewise – only live happily together. The flirting and all other such nonsense is not worth mentioning, and where it occurs the fault generally lies in the teacher, and a great deal more with the males than the females.

Economics may have influenced the decision of some churches to open their choirs to women. Some correspondents suggested that lady choristers would fill half-empty churches – with men, who might then contribute to church finances. One correspondent reported that offerings in a Birmingham church had increased by a third since ladies had joined the choir. Other correspondents, however, believed that having female choir members would attract the wrong kind of men – those who belonged in theatre stalls, not in church pews. In general, when church music was part of the liturgy, and choir members the official representatives of the priest at the altar, women were excluded.

By 1892 when the Reverend Hugh Reginald Haweis described in detail his successful coup d’etat in which he introduced a mixed choir into the services of St James, Marylebone, the controversy had quieted down in the press.20 Writing to the Daily Telegraph at the end of that newspaper’s debate on the lady chorister question, a correspondent with initials D.L. sensibly had suggested that the decision whether to have female choir members, and whether they should wear surplices, should be based on a church’s particular circumstances. Any church should use the best voices available, male or female. And as the newspaper editor concluded:

The main desideratum, after all, is that this singing should be tuneful and harmonious, such as to intensify devotional feeling, not to mar or interrupt it. Whether it be performed by boys or girls, surpliced or unsurpliced, would seem altogether a secondary consideration.

But the last word goes to the female correspondent who believed it was high time men made way for women in the choir stalls and in the pulpit:

SIR – We women scarcely expect much quarter from men who find it so comfortable to be placed foremost in the Church, as elsewhere. They do not imitate the Apostle so fondly quoted, for he was courteous and chivalrous – note his words on our side: ‘Help those women who have labored with me in the Gospel, whose names are in the Book of Life.’ Surely this is proof positive of woman’s call to the work she is so nobly fitted for. I suppose the women will be clothed in white in heaven as well as the men, although it is only an ecclesiastical monopoly here. – Yours faithfully, CASSANDRA.

Notes

- John Mason Neale, Church Enlargement and Church Arrangement (Cambridge: Cambridge Camden Society, 1843), 15.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 16.

- Lucy Lyttelton Cameron, The Singing Gallery (London: Houlston, c. 1830?)

- Alex R. Vidler, The Church in an Age of Revolution, 1789 to the Present Day (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971), 49–50.

- Marvin R. O’Connell, The Oxford Conspirators: A History of the Oxford Movement 1833–45 (London: Macmillan, 1969), 23.

- Dale Adelmann, The Contribution of the Cambridge Ecclesiologists to the Revival of Anglican Choral Worship 1839–62 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997), x, xii.

- James F. White, The Cambridge Movement: The Ecclesiologists and the Gothic Revival (Cambridge: At the University Press, 1962), 38–39.

- Neale, Church Enlargement, 6; idem, A Few Words to Churchwardens on Churches and Church Ornaments No. 1, Suited to Country Parishes, 8th ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1841), 12; Idem, A Few Words to Churchwardens on Churches and Church Ornaments No. II, Suited to Town and Manufacturing Parishes, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1841), 6.

- White, Cambridge Movement, 97.

- A Chorister, ‘Correspondence’, Musical Times 2 (1848): 162.

- An ‘Angelic Quire’, Daily Telegraph, 14–19 August 1889.

- ‘Ladies’ Surpliced Choirs’, Musical Times 30 (1889): 525; ‘Lady Choristers’, Musical Herald, n.s., no. 9 (1889): 197; Samuel Day, ‘Ladies’ Surpliced Choirs’, Musical Times 30 (1889): 555; Hugh R. Haweis, ‘The Choir of St. James’s, Marylebone’, Illustrated London News, 20 August 1892, 242.

- ‘Ladies’ Surpliced Choirs’, Musical Times 30 (1889): 555.

- Ibid.

- “Ladies’ Surpliced Choirs’, Musical Times (1889): 555–56.

- Haweis, ‘Choir’, 242.

- Cantatrice, ‘Employment of Female Voices in Church Choirs’, Musical Times 27 (1886): 742; M.J. [Marie Julia] Cope, ‘Employment of Female Voices in Church Choirs’, Musical Times 28 (1887): 49.

- W. Lyon Blease, The Emancipation of English Women (New York: Arno, 1910), 122.

- Ibid.