Music Lessons from The Girl’s Own Paper

When I first came across a few annual volumes from the 1880s of The Girl’s Own Paper (TGOP) in the stacks of a major academic library, I was searching for information about female organists in nineteenth-century England.1 My efforts were rewarded. Illustrations of young women on the organ bench in church lofts, fiction featuring young heroines who played the organ, replies to correspondents about organs and organ playing, reviews of organ books, and occasional music scores composed for American organ or harmonium all suggested that organists were among the magazine’s readers.

Perusal of these and additional volumes of TGOP revealed a rich musical content not limited to the organ in this weekly miscellany for girls published in London by the Religious Tract Society (RTS) beginning in 1880. Voice, piano, violin and their performers are well represented, and other instruments such as harp, harmonium, guitar and concertina also appear. Although not a music journal such as the concurrently published Musical Standard, Musical Times and Musical World that catered to professional and amateur musicians in concert and church settings, TGOP nevertheless clearly considered music a worthy topic for its readers. To place this worthiness in context, of the two so-called feminine accomplishments for which TGOP allotted the most space, musical content appeared more frequently than the numerous articles and prize competitions featuring plain and fancy needlework.

Music topics in a general interest periodical were not unique to TGOP. Publications such as Atalanta, Girl’s Realm, The Strand Magazine and The Windsor Magazine, all begun in the 1890s, included music in fiction, nonfiction, illustrations, poetry and, in some, an occasional music score. What set TGOP apart was its greater amount of musical content. Of the 1,500 weekly issues of TGOP I reviewed spanning 3 January 1880 when the magazine began through 26 September 1908, after which publication was monthly, over 1,300 – approximately 88 per cent – include some type of musical content whether a music score, an instalment of serialized fiction about a musician, music-related nonfiction, poetry with musical relevance, an illustration depicting music making, or a reply to a musical correspondent. The numbers are even higher – over 1,400 issues, approximately 98 per cent – when all chapters of a story in which music makes only a cameo appearance are included. And all 47 extra issues of TGOP printed for the Christmas and, most years, summer holidays include music in topic or score as well.

Although TGOP is the subject of at least two books and is mentioned in others that chronicle the rise of publications targeting children and women readers, none focuses on music as one of the magazine’s components. In Great-Grandmama’s Weekly: A Celebration of The Girl’s Own Paper 1880–1901, Wendy Forrester provides an overview of the magazine’s contents, which she categorizes as the Modern Woman, Health and Beauty, Fiction, Doing Good, Dress, Features, the Domestic Arts, Competitions and Answers to Correspondents. Terri Doughty’s Selections from The Girl’s Own Paper, 1880–1907 reprints pages about Household Management, Conduct, Self-Culture, Education, Work, Independent Living and Health and Sports, each section introduced by the author. In Constructing Girlhood Through the Periodical Press, 1850–1915, Kristine Moruzi, who examines five British girls’ periodicals in print between 1850 and 1915 that ‘reflect the shifting nature of girlhood during this period’, devotes a chapter to coverage of health, fitness and beauty in The Girl’s Own Paper.2

Ray Hindle’s Oh, No Dear! Advice to Girls a Century Ago and June Grace’s Advice to Young Ladies from the Nineteenth-Century Correspondence Pages of The Girl’s Own Paper are edited collections of replies selected from Answers to Correspondents columns in TGOP. Few of Hindle’s 500 selections from 1880 to 1882 and none of Grace’s 32 selections from the nineteenth century are music related, and neither author gives a rationale for choosing those particular answers.3

Honor Ward’s online The Girl’s Own Paper Index, currently accessed at http://maths.dur.ac.uk/~tpcc68/GOP/welcome.html, provides links to fiction and nonfiction content, some of it music related, in the weekly – later monthly – magazine and its extra holiday issues from 1880 through 1941 by author and by subject, as well as background information about TGOP.

The important role that music played in the lives of young women, fictional and actual, in England during the long nineteenth century as reflected in novels and periodicals has been the focus of essay collections and monographs in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. For example, in her essay ‘Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction’ in The Lost Chord edited by Nicholas Temperley, Mary Burgan found that over the course of that century the piano served as a social prop, symbol of confinement and instrument of rebellion in women’s lives. In The Idea of Music in Victorian Fiction, a collection of essays edited by Sophie Fuller and Nicky Losseff, Jodi Lustig’s ‘The Piano’s Progress: The Piano in Play in the Victorian Novel’ considers how what the piano signifies as an instrument of domestic music making and cultural capital in one novel could suggest its antithesis in another.4

For Phyllis Weliver, in Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, the discrepancies between fiction’s portrayal of musical women and actual trends of music making reveal how literature dialogued with real life, either encouraging or condemning music’s traditional place in women’s lives. Paula Gillett’s Musical Women in England, 1870–1914 uses fiction, poetry, music journals and girls’ and women’s magazines – including TGOP – to understand highly contested perceptions of female musicians in late-Victorian culture.5

Situated within the broader context of music and literature, my book offers readers and scholars in both fields an easily accessible database for a single periodical, which circulation figures, self-reported praise and reader response suggest was widely read and popular among Britain’s female readers of all ages. By the editor’s acquired information, as he told correspondents Grey Hairs in 1880, A Scot in 1881 and A.M. in 1893, TGOP readers were from all walks of life and nearly all nationalities.6 Correspondents’ ages ranged from six to 80, and readership stretched to the Continent, the British colonies and beyond. Circulation figures support the editor’s claims of early success: Patrick Dunae cites an initial weekly circulation of 250,000 copies, declining to 189,000 in 1889.7 James Mason pictured the number of TGOP sold prior to its thousandth issue as the height of 56 Mount Blancs or the length of the equator’s circumference with a bit of overlap.8

In its first year TGOP already had caught the favourable attention of contemporary publications as ‘a storehouse of amusement and instruction of the best kind’ (The Queen), a paper ‘we should like to see placed in the hands of our sisters and daughters’ (School Newspaper), ‘one of the best family magazines now publishing’ (Peterboro’ Advertiser) and recommended ‘to the attention of every parent in the land’ (South Wales Press). Singled out specifically was ‘How to Play the Piano’ by Arabella Goddard, which was so full of good sense and so rich in practical suggestions, that some of the “girls” who already pride themselves on their powers as executants will find it worth their while carefully to study the advice here given and act upon it (Rock).9

After exploring the inclusion of material related to women organists in TGOP, I returned to the magazine to examine how it treated music as an accomplishment for young gentlewomen in late Victorian and Edwardian England. Over time I located and perused every issue in every annual volume of TGOP and all but one of the extra holiday issues from 1880 through the end of 1910 and compiled an index of all their music-related material.10 What I found regarding musical accomplishments supported other scholarship about women’s music making in the long nineteenth century – that the musically accomplished young lady was expected to live her life so that she did not lose as an ideally feminine woman what she gained in proficiency as a musician.

Of more interest as I studied the musical content in TGOP was the shift in women’s music making from a feminine accomplishment to an increasingly professional role within the discipline. Over its first 30 years TGOP content was designed to appeal to novice, practising and committed musicians, since the magazine had readers at all three levels. For example, musical novices could learn about the instruments of the orchestra so they could enjoy concerts. Notices and reviews of new music, as well as music scores, assured musical practitioners of suitable repertoire. Committed musicians found detailed analyses of piano compositions, especially by Beethoven, and explanations of musical forms. All readers could learn about performers, composers and their music, as well as apply their skills to occasional competitions in music composition. But that content changed over time in response to the changing role of music in women’s lives. The three-tier focus on music making that appeared within each volume characterized the magazine’s musical content across the three decades as well.

The first decade of publication focused on the novice musician. All of the ‘how to’ primers on playing musical instruments were printed between 1880 and 1889, from singing a song in Volume 1 to playing the zither in Volume 10. Music making, centred in the home, had much to do with setting a solid foundation, not only for musical competence but also for musical courtesy – a young gentlewoman never made her practice a nuisance to others. A good musical ear could lead to a musical calling if one had the right temperament and approached that calling with selflessness, truth and purity.

In the second decade TGOP content began to reflect a shift of young ladies’ musical accomplishment from avocation to vocation, from amateur to professional. The magazine was raising its musical bar higher in part as a reflection of higher societal expectations for music making in general. Singing and playing were no longer a mere pastime, and no one without decided musical talent should labour over music lessons and daily practice. Informative articles of the 1890s built on the primers of the 1880s.

By the third decade of the magazine’s publication, the transition from music as pastime to music as profession was more complete, especially beginning in 1908 with the change in the magazine’s editorship. TGOP content now was directed at committed musicians whose exceptional talent for music would lead them to careers as vocalists or instrumentalists. Piano playing received the most focus and offers a case study.

The Passing of ‘The Piano Girl’

‘Here is a pretty paradox,’ wrote James Huneker in his essay ‘The Eternal Feminine’ in Overtones: A Book of Temperaments first published in 1904: ‘the piano is passing and with it the piano girl, – there really was a piano girl, – and more music was never made before in the land!’ The author was reflecting on an era during which the young woman and the piano had been linked closely in nineteenth-century Europe and America. ‘Every girl played the piano,’ he continued. Not to play it ‘was a stigma of poverty.’11 Piano manufacturers, music teachers, composers and music publishers all had benefitted from the steady rate at which the piano took root in homes, aided in part by the hire purchase system described in Cyril Ehrlich’s book The Piano that enabled British families without sufficient funds on hand to buy a cottage piano for a down payment and monthly instalments over three years.12

The ubiquitous household instrument may have found its most ardent executants in England’s middle-class maidens caught up in the piano mania that for a time seemed unabated, chronicled, for example, by Ehrlich and by Arthur Loesser.13 ‘Liszts in petticoats have been so numerous, as during the past twenty-five years to escape classification,’ Huneker continued. ‘It was the girl who did not play that was singled out as an oddity.’14

The time span to which the author refers coincides with the first 30 years of TGOP. A close reading of its weekly – and later monthly – issues over the first three decades reveals the piano’s influence not only in music scores, but also in fiction, nonfiction, fashion, Varieties, poetry, Answers to Correspondents and, starting in 1901, the Fidelio Club, a monthly column offering analyses of pieces and replies to readers’ questions. The musical journey of pianists through the pages of TGOP offers new insight into the changing role of music in the lives of young women in late Victorian and Edwardian England.

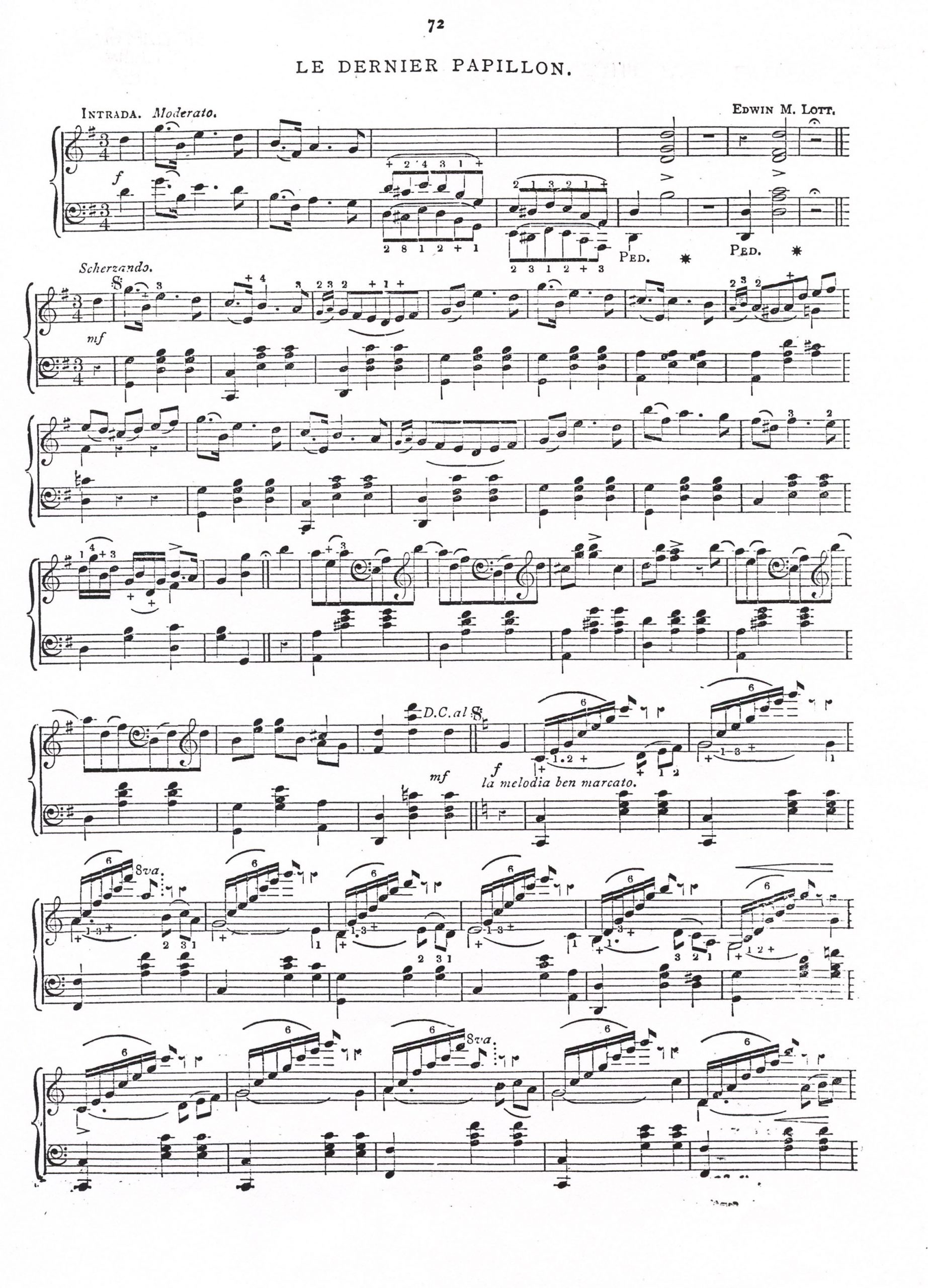

Like some other general interest magazines of the time, TGOP included music scores in its issues. Although most were for voice with piano accompaniment, piano solos appeared beginning in 1881. The first, ‘Le Dernier Papillon’– The Last Butterfly – with its nod to Robert Schumann, is a two-page Intrada in G major by Edwin M. Lott (Figure 1). Thirty more piano solos appeared over the next three decades, by little-known composers, regular contributors such as Clara Macirone and Myles Foster and composers of international stature such as Clara Schumann and Hubert Parry. An average of two pieces a year appeared through 1893; one appeared in 1895 – a three-page Mazurka in A minor by Lady Thompson (Kate Loder) – but 10 years elapsed before another piano solo was forthcoming – a three-page Gavotte in D major with Musette in the parallel minor by Cécile Hartog.

Figure 1 First piano piece printed in The Girl’s Own Paper, ‘Le Dernier Papillon’ (Edwin M. Lott), The Girl’s Own Paper 3 (29 October 1881): 72–3 (Lutterworth Press)

The piano was heard in fiction as an instrument teaching some of life’s important lessons. In ‘Our Patty’s Victory’ of 1881, the victory is over the selfish desire, however well intended, to learn to play the piano. Patty’s large farm family had neither a piano nor funds for lessons, but a young pianist who lived nearby offered to teach Patty for free. When the girl Patty hires to help her mother during lessons sets the chimney on fire, breaks the teapot and scalds the baby, a night of prayerful agonizing convinces the daughter that her duty clearly lies with her family’s daily round in which the piano plays no part. ‘The Mother and the Wonder-Child’ by Ethel Turner, which ran in 1901, addresses the issue of child prodigies. While eight-year-old Challis and her mother are forging the young pianist’s career overseas in Europe, the rest of the family remains home in Australia in financial difficulty kept from the world travelers. The eventual reunion is joyous for all but Challis, who no longer fits in – she had played concerts before royalty but had never learned to play like a normal child. The author’s message is clear: Proud parents should weigh the benefits of nurturing genius in a talented child against the risks of separation and implied favouritism.

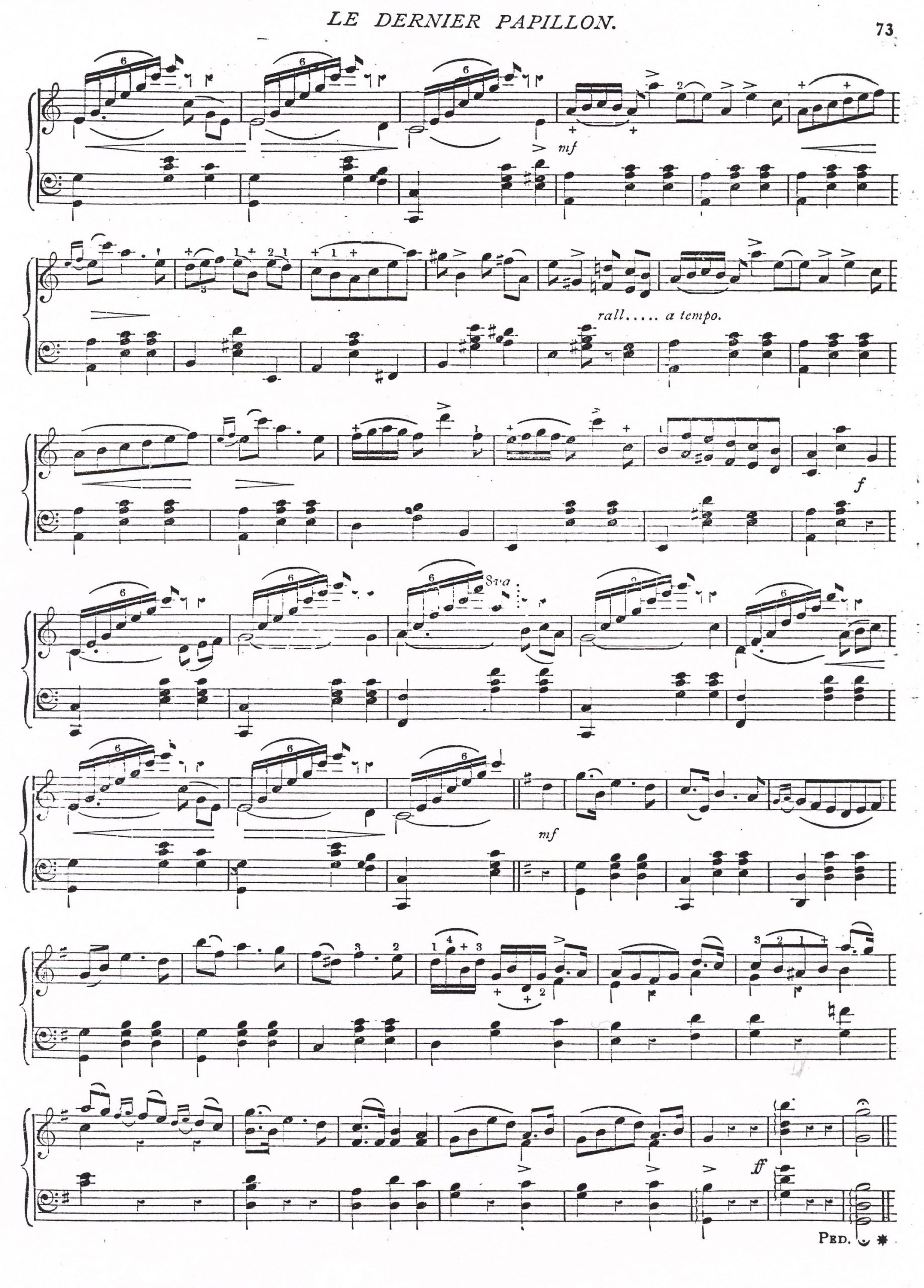

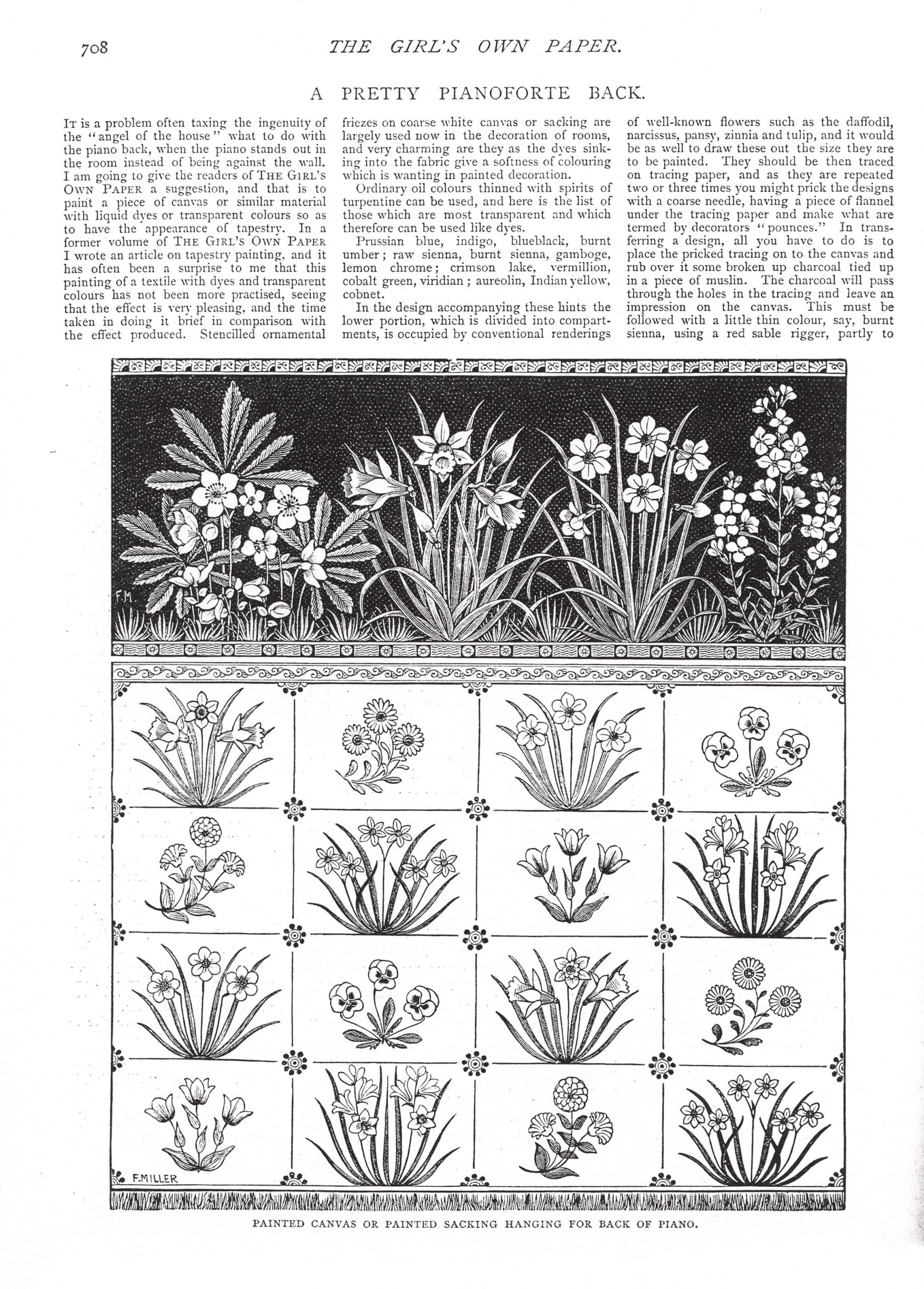

The piano appeared even more prominently in the magazine’s nonfiction, with instructions on how to purchase and maintain it, drape it, select music for it and play it. An article in 1881 offered advice on ‘How to Purchase a Piano and Keep It in Good Order’. By 1886, the importance of the right piano maintained in pristine condition merited a four-part series on that topic. The next year piano maintenance extended to its tuning – a skill that female pianists could learn for paid employment. Today’s readers might consider making decorative drapes for the piano a trivial pursuit, but at a time when the piano was likened to an altar in the home, its accoutrements were important, and TGOP offered its readers designs to grace the piano front and back beginning in 1880 and still appearing as late as 1899 (Figure 2 and Figure 3).15

Figure 2 ‘Pianoforte Fronts: and How to Decorate Them’ (Fred Miller), The Girl’s Own Paper 6 (4 July 1885): 628 (Lutterwoth Press)

Figure 3 ‘Painted Canvas or Painted Sacking Hanging for Back of Piano’, in ‘A Pretty Pianoforte Back’, The Girl’s Own Paper 18 (7 August 1897): 708 (Lutterworth Press)

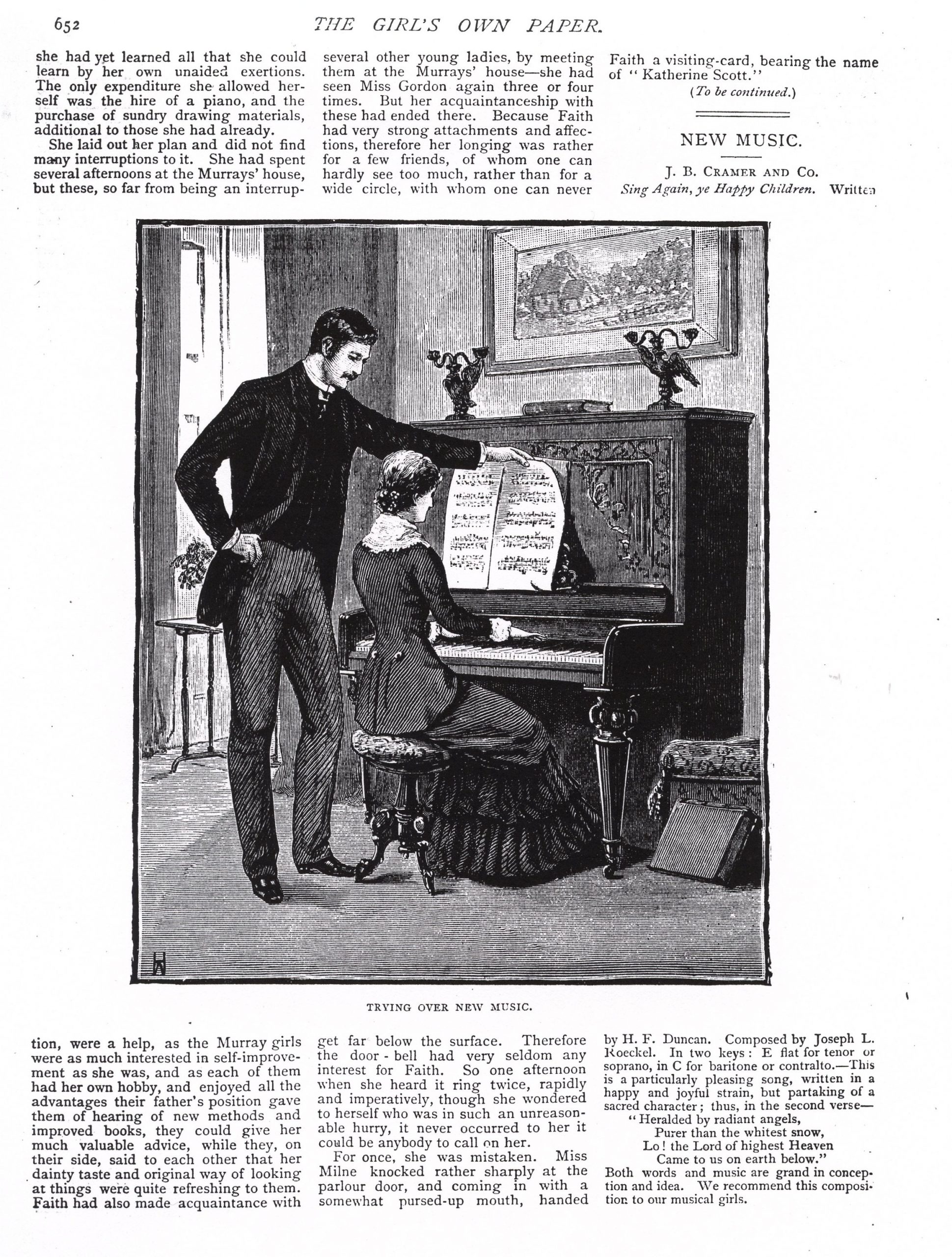

Music scores in TGOP must not have been sufficient to keep musical readers singing and playing contentedly. So many readers wrote to the magazine asking for advice on purchasing music that in 1881 the magazine began a monthly ‘list of new music, with short descriptions of their character’; an illustrated page from Volume 3 is shown in Figure 4.16 The regular column, which included piano music, vowed to review no compositions judged poor music or in bad taste. The column tapered off through 1894, lapsed for three years, then reappeared in 1898 in a new format more specific to voice type, instrument and style of music, written by composer Mary Augusta Salmond.

Figure 4 ‘Trying over New Music’, in ‘New Music’, The Girl’s Own Paper 3 (8 July 1882): 652 (Lutterworth Press)

Arabella Goddard offered the first primer on piano playing, in 1880. Her belief that it was never too late to learn must have pleased older readers eager to pursue this popular accomplishment. Her expectations for girls of any age were exacting: lots of scales, sightreading, memory work and avoiding all affected sentiment. Lady Benedict followed with ‘How to Improve Your Pianoforte Playing’ in the next volume. Authors assumed a beginning level of musical expertise and intended their instruction to supplement, not replace, formal lessons by a reputable music master.

Oliveria Prescott anthropomorphized the piano, which was not always pleased with the touch it felt on its keys and had no qualms making its views known. ‘It behooves us, therefore, to be very careful what we say to the piano,’ she warned, ‘and if we do not want our hearers to think we are hard and unkind, or nervous, or unthinking of the music, we must not teach the piano that such is the case.’17

In the magazine’s second decade, Fanny Davies, a Clara Schumann protégé, offered instruction ‘On the Technique of the Pianoforte’ to help earnest students lay a solid foundation for future success. Talent might be God-given, she said, but ‘loving patience and long earnest study is necessary for its development, however great the gift’. Technique was a means to that end, ‘but not the end itself’.18 In ‘Some Remarks on Modern Professional Pianoforte Playing’, William Porteous offered Davies as an excellent example of the Classical Style.

Lady Benedict and Prescott guided pianists through Mendelssohn Songs Without Words and Beethoven sonatas. In ‘On the Choice of Pianoforte Pieces’, concert pianist Ernst Pauer, an advocate of the ‘simpler is better’ philosophy, stressed the prudence of playing an easier piece correctly rather than scrambling a more difficult one. His ‘Impressions of Celebrated Pianoforte Pieces’ followed. Other articles offered pianists lessons on practising and fingering.

In its third decade, beginning in 1901 TGOP offered pianists among its readers the Fidelio Club to guide them in their practice, conducted by Dublin-born concert pianist Eleonore d’Esterre-Keeling. Three months after its start, the club had over 100 members, suggesting it filled a need. At six months that number had doubled, and by June 1903 was up to 400.

When Charles Peters, the magazine’s editor since its first issue, died at the end of 1907, new editor Flora Klickmann did not continue the Fidelio Club. But her interest in the piano led to articles by concert pianists such as Joseph Hofmann, who contributed five between 1908 and 1910.

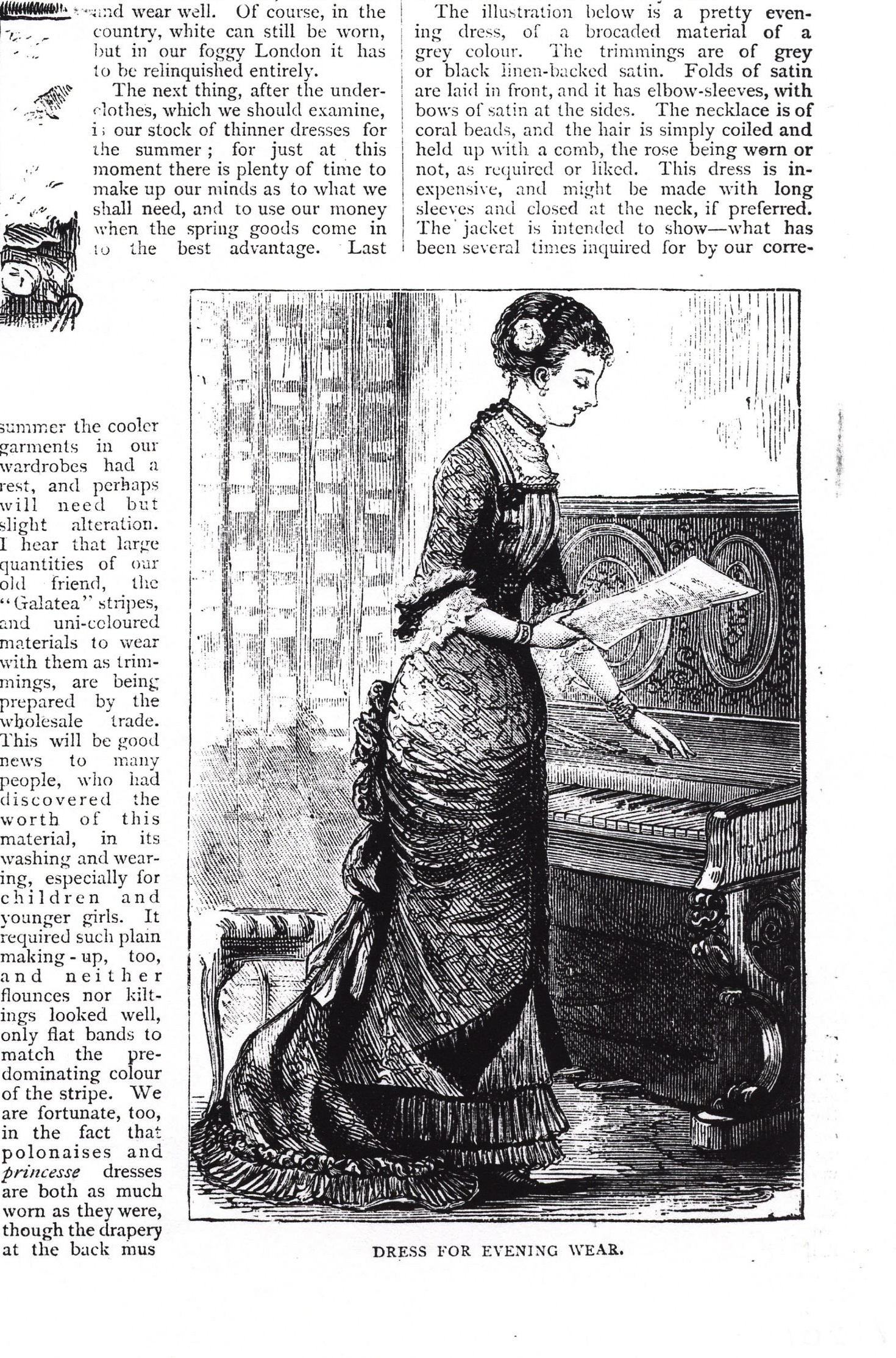

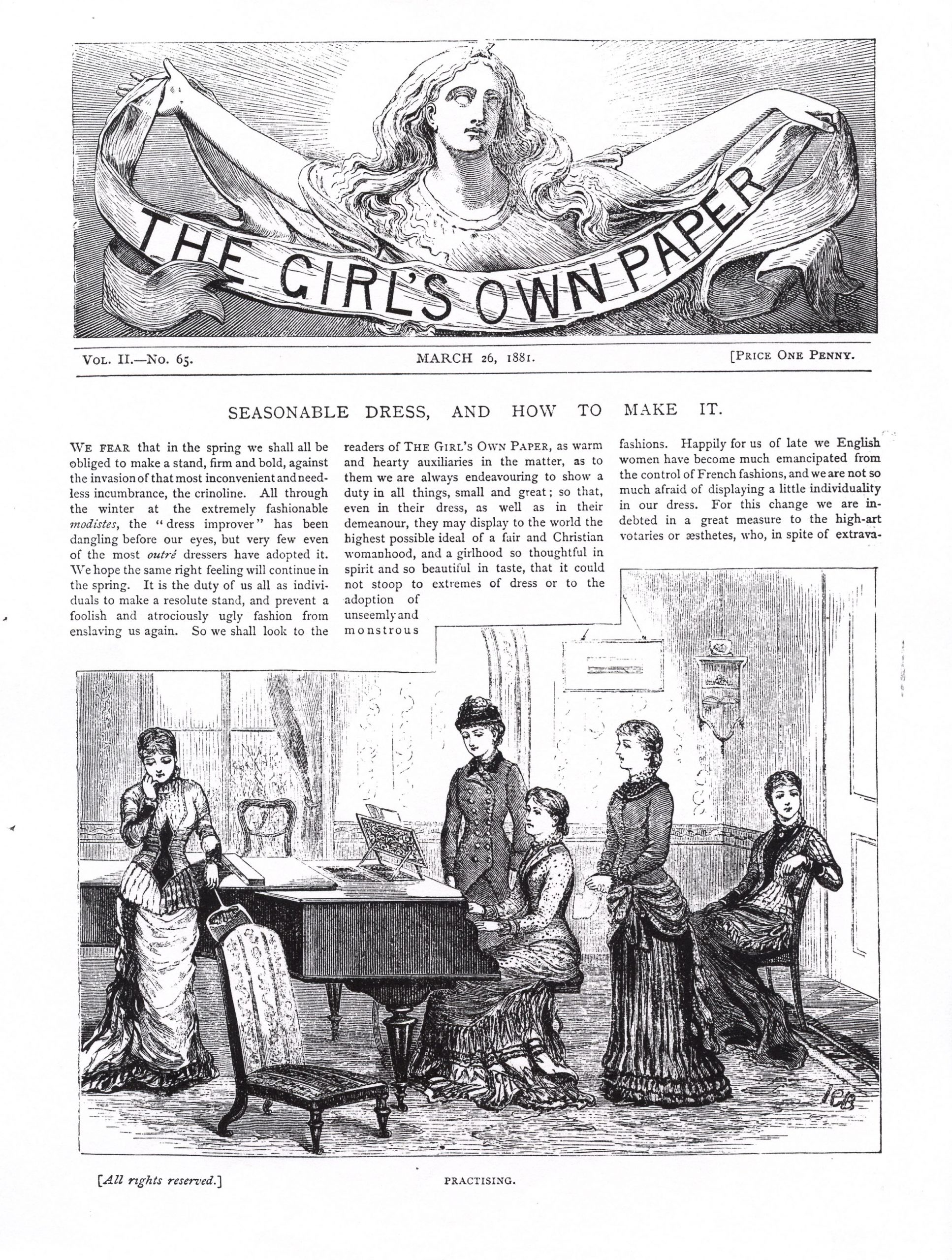

Three other types of content mark pianists’ musical journey through TGOP: fashion illustrations, the Varieties column and poetry. In a fashion article of 1880, ‘Dress for Evening Wear’ shows a young woman standing at an upright piano, her eyes focused on sheet music in her right hand, her left hand poised over the keyboard (Figure 5). A year later the pianist sits at a grand piano (lid closed) ‘Practising’ (Figure 6). By 1907 a more assured-looking pianist sits at a grand piano (lid open), turning a page of music while accompanying a vocalist (Figure 7). Fashions changed, as did pianos, but the subliminal message remained the same: the best-dressed young women were also accomplished pianists.

Figure 5 ‘Dress for Evening Wear’, in ‘The Dress of the Month’, The Girl’s Own Paper 1 (27 March 1880): 201 (Lutterworth Press)

Figure 6 ‘Practising’, in ‘Seasonable Dress, and How to Make It’, The Girl’s Own Paper 2 (26 March 1881): 401 (Lutterworth Press)

Figure 7 ‘An excellent example of a wide grey and white striped material’, in ‘How a Girl Should Dress’ (Norma), The Girl’s Own Paper 28 (29 June 1907): 617 (Lutterworth Press)

Perhaps to inspire musical readers’ efforts but not inflate their egos, in the Varieties column silly tidbits share space with serious ones. Some of the former spoof the craze for piano playing, as in:

MUSICAL PROGRESS. ‘How are you getting on with the piano?’ asked Alphonso of his best girl.

‘Oh, very well; I can see great progress in my work.’

‘How is that?’

‘Well, the family that lived next door moved away within a week after I began to practise. The next people stayed a month, the next ten weeks, and the family there now have remained nearly six months.’19

Poetry, too, has musical titles, text and illustrations. In ‘The Piano and the Player’ of 1892, for example, William Luff inspired readers: ‘Alone we are mute and silent; / But if the great Master’s hand / Is laid on the idle keyboard, / What music may cheer the land!’20

But in 1899 some keys remained idle, as noted in ‘On a Very Old Piano: Lately Seen in a London Shop Window, and Labeled, “Cash Price, Two Guineas”’. ‘Poor faded, long-neglected thing,’ the unnamed poet begins, ‘Not worth a glance / From eyes disdainful as they pass, / While you stand there, the sport, alas! / Of circumstance.’ The little maid no longer played quaint old tunes; the young woman no longer played to her lover. ‘Your reign is over; here you wait, “Cash price, Two Guineas” is your fate / In London Town.’21 In 1891 ‘A Use for Old Pianos’ giving detailed instructions how to turn an unused upright piano into a combination bookcase, writing desk and cabinet had hinted at the same fate.

One way to determine what TGOP’s pianists actually were doing musically is to examine the Answers to Correspondents column. Replies about music appeared in most issues. Although no questions were printed, the column offers insight into readers’ participation in music. A common question apparently asked was how long to practice daily. The editor told over a dozen correspondents between 1880 and 1892 that daily practice should not exceed one-and-a-half hours. He warned Kitten against ‘immoderate practice’ that could become a nuisance and advised that ‘half an hour’s really good practice is preferable to any amount of indifferent careless work’.22

The editor was brusque with readers who likely tried to impress him with excessive practice. He hoped Topsey did not ‘live in a row, square or semi-detached house, or we pity the neighbours who must listen to a five hours’ practising, in one house alone, every day! It is well that THE GIRL’S OWN PAPER is not edited next door.’23 Yet the editor told Red Riding Hood, whose hands ached from practice that obviously exceeded an hour and a half a day, ‘We wish your complaint were more common.’24 Faced with such contradictions, readers could become confused when using TGOP as their source of musical information. But the magazine did not deviate from two messages: One’s music making should never be a nuisance to others, and only those readers with a good ear for music should pursue that accomplishment.

Social downgrading of the piano – Ehrlich’s term – was evident in correspondent E. Litchy who wanted to practise on her mistress’s piano when the mistress was away, an action that the editor said would betray her employer’s trust, ‘not to speak of the great annoyance to neighbours within hearing distance of your mistakes’.25 And Kate Wren ‘might as well “cry for the moon” ’ regarding piano practice in her current domestic position.26

As the magazine ended its first decade, A Templar writing about ‘The Girls of To-day’ noted the new standard of perfection detailed in Lady Catherine Milnes Gaskell’s ‘Women of To-day’, an article published in the journal Nineteenth Century in 1889 that extended to musical accomplishments.27 Mediocre was ‘happily banished to limbo’, A Templar wrote.28 If a woman must live by her music, she would excel in it. Gaskell had raised the bar for musical women of TGOP’s second decade, but hers was not a new standard. The magazine had been preaching against mediocrity from its start, when Alice King, in ‘What Our Girls May Do’, urged readers in 1880 to break down the notion of respectable English families that all daughters should be taught to play the piano.

Young women of the 1890s were cultivating broader academic, occupational and recreational interests. Although they still pursued music as an accomplishment, it was not their only option for pleasure and profession. Like their sisters in wider society, TGOP readers were falling under the influence of the New Woman, and music soon would be viewed through her spectacles.

Little content in TGOP sympathized with or supported the New Woman, however. Some replies to correspondents revealed readers interested in pursuing musical examinations and degrees, including doctorates in music. Generally, the magazine charted a course similar to its previous 10 years, though content began to reflect a shift from music as avocation to music as vocation, from amateur to professional.

In 1900, the editor suggested that Inca, short on time but long on desire to be a musician, learn singing instead of piano that required more practice, but told her not to be distressed at not being a musician: ‘The time has gone by when every woman is expected to play or sing.’29 Nor did every woman want to play or sing.

Musical accomplishments seemed at risk of disappearing in clouds of dust raised by young women on their bicycles – a trend the Musical Times watched with concern in 1896, identifying the bicycle as a ‘new and most formidable enemy’ for luring its riders off the piano stool.30 But not necessarily, as Mrs George de Horne Vaizey noted in TGOP of the fictional Rendell sisters in ‘A Houseful of Girls’, which ran in 1900. Young women were shunning ‘promiscuous accomplishments’ in order to do one thing well, which could be piano playing. 31 Yet musical accomplishment now extended from piano keys to business savvy and common sense, beyond the practice room out into the world.

By the end of the third decade of TGOP, the transition to music as a profession was more complete. Intelligent listening at orchestral concerts, the topic of a two-part article in 1884, had expanded to an 11-part series in 1903 with expectations for detailed study of individual instruments and ability to follow along with a full score. Musical content of the magazine had shifted primarily to piano playing.

In Girl’s Only, a book about gender and popular fiction in Britain, Kimberly Reynolds suggests that from 1880 to 1910 TGOP ‘seems to have operated in a “prefigurative” way’, making a ‘bridge between the rapidly changing experience of being young and female in British society and the residual notion of what it should be like. New ideas about education, careers for women, health and exercise were made acceptable by being related to traditional values, behaviour, and occupations.’32 TGOP reflected traditional values and was not concerned, Reynolds states, with providing a platform for women ‘actively engaged in challenging conventional attitudes’.33 The magazine accepted but did not encourage a career as a professional pianist, for example. This stance was reinforced in articles that offered aspiring professional musicians a reality check. In the multi-part ‘Music as a Profession’, beginning in 1903, for example, A. Foxton Ferguson offered the thousands of students studying music as a means to earn their livelihood – though often in a light-hearted manner – a sobering fact: only one per cent of them would succeed. In support of his thesis the author addressed issues of superficial glamour, well-meaning friends, masters, agents and concert giving, and wealth. Madame Nellie Melba’s 1909 ‘Why So Many Students Fail in the Musical Profession’ was aimed at the numerous young women who traveled abroad inadequately equipped with either money or talent to support their music studies.

Emil Reich’s anachronistic view in 1908 that girls should leave the piano and violin alone and focus instead on the harp, which would aid them in singing beautiful music, likely had little influence on pianists who sought professional status. They had already crossed that bridge and were not looking back. In A Magazine of Her Own? Margaret Beetham notes the periodical’s diversity that allows different viewpoints and empowers readers to choose what they want to read and how carefully, accepting or rejecting text at will.34 Discerning readers thus could have taken Reich’s ‘The English Girls of To-morrow’ with a grain of salt.

Huneker offers the last word concerning the ‘piano girl’. The current generation of girls could thank their older sisters for ‘immunity from useless piano practice’, he said. Instead, today’s young woman ‘golfs, cycles, rows, runs, fences, dances, and pianolas! While she once wearied her heart playing Gottschalk, she now plays tennis, and she freely admits that tennis is greater than Thalberg.’35 She goes to a piano recital if she wants to hear ‘the “lilies and languors” of Chopin and the “roses and raptures” of Schumann’ that she has forsaken by choice. The recitalist might be a woman, however, for ‘new girls’ who had a musical gift still did play the piano with ‘consuming earnestness’. ‘We listen to her,’ Huneker continues, ‘for we know that this is an age of specialization when woman is coming into her own, be it nursing, electoral suffrage, or the writing of plays’.36 Or, he might have added, in the musical journey to becoming a professional pianist.

This book catalogues the musical journey of ‘the piano girl’ and others through the first three decades of TGOP, from the magazine’s start-up in 1880 through the first change in editorship. TGOP’s first editor, Charles Peters, died at the end of 1907, and the magazine changed from a weekly to a monthly issue under the new editor Flora Klickmann beginning with the next annual volume. By 1910, the catalogue’s cutoff, the magazine clearly reflected Klickmann’s stamp. Choice of an annotated catalogue format allows a means to determine what musical content is found in TGOP, delineated in a chronological listing by volume. Further division of that content into topical indexes reveals the magazine’s diversity of approach to the subject of music. The catalogue format does not reveal why the magazine included so much music, however. The answer may rest in large part on the publisher’s view of the role music should serve in the lives of TGOP readers and the backgrounds of the magazine’s first two editors who were themselves musicians.

Music Lessons from The Girl’s Own Paper continues.

Notes

- Judith Barger, Elizabeth Stirling and the Musical Life of Female Organists in Nineteenth-Century England (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007).

- Wendy Forrester, Great-Grandmama’s Weekly: A Celebration of The Girl’s Own Paper 1880–1901 (Guilford and London: Lutterworth, 1980); Terri Doughty, ed., Selections from The Girl’s Own Paper, 1880–1907 (Peterborough, Ontario and Orchard Park, NY: Broadview, 2004); Kristine Moruzi, Constructing Girlhood Through the Periodical Press, 1850–1915 (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012).

- Roy Hindle, ed., Oh, No Dear! Advice to Girls a Century Ago (London: David and Charles, 1982); June Grace, ed., Advice to Young Ladies from the Nineteenth-Century Correspondence Pages of The Girl’s Own Paper (N.p.: Author, 1997).

- Mary Burgan, ‘Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction’, in The Lost Chord: Essays on Victorian Music, ed. Nicholas Temperley (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989), 42–66; Jodi Lustig, ‘The Piano’s Progress: The Piano in Play in the Victorian Novel’, in The Idea of Music in Victorian Fiction, ed. Sophie Fuller and Nicky Losseff (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004), 83–104.

- Phyllis Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900: Representations of Music, Science and Gender in the Leisured Home (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2000); Paula Gillett, Musical Women in England, 1870–1914: ‘Encroaching on All Man’s Privileges’ (New York: St Martin’s, 2000).

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Grey Hairs’, TGOP 2 (2 October 1880): 15; ‘Answers to Correspondents: A Scot’, TGOP 2 (17 September 1881): 816; ‘Answers to Correspondents: A.M.’, TGOP 15 (4 November 1883): 80.

- Patrick Dunae, ‘Boy’s Own Paper: Origin and Editorial Policies’, The Private Library 2nd ser. 9/4 (1976): 211, 217.

- James Mason, ‘Looking Back: A Retrospect, with Some Surprising Figures and a Presentation to the Editor’, TGOP 20 (25 February 1899): 341.

- Samuel Green, The Story of the Religious Tract Society for One Hundred Years (London, 1899), 288. TGOP content that may be found in the Catalogue that follows is not cited unless a quotation.

- I could not locate ‘The Morning of the Year’ Christmas and New Year’s number for TGOP Volume 15, 1893.

- James Huneker, Overtones: A Book of Temperaments (New York: Scribner, 1904), 286, 289–90.

- Cyril Ehrlich, The Piano: A History (London: Dent, 1976), 98–104.

- See Ehrlich, Piano; and Arthur Loesser, Men, Women and Pianos: A Social History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954).

- Huneker, 291.

- ‘Are We a Musical People?’ Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science, and Art, 4th ser., 18 (2 July 1881): 418.

- ‘New Music’ TGOP 2 (29 January 1881): 287.

- Oliveria Prescott, ‘Touching the Pianoforte ‘, TGOP 8 (12 March 1887): 378.

- Fanny Davies, ‘On the Technique of the Pianoforte: A Practical Talk to Earnest Students ‘, TGOP 12 (25 October 1890): 53.

- ‘Varieties: Musical Progress’, TGOP 12 (15 November 1890): 107.

- William Luff, ‘The Piano and the Player’, TGOP 14 (17 December 1892): 177.

- ‘On a Very Old Piano: Lately Seen in a London Shop Window, and Labeled, “Cash Price, Two Guineas”’, TGOP 20 (10 June 1899): 590.

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Kitten’, TGOP 3 (28 January 1882): 286.

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Topsey’, TGOP 3 (30 September 1882): 847.

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Red Riding Hood’, TGOP 2 (9 April 1881): 448.

- Ehrlich, Piano, 93; ‘Answers to Correspondents: E. Litchy’, TGOP 16 (7 September 1895): 784.

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Kate Wren’, TGOP 12 (28 February 1891): 352.

- Catherine Milnes Gaskell, ‘The Women of To-day’, Nineteenth Century 26 (November 1889): 776–84.

- A Templar, ‘The Girls of To-day’, TGOP 11 (21 December 1889): 179.

- ‘Answers to Correspondents: Inca’, TGOP 21 (13 January 1900): 239.

- ‘The Pianoforte and Its Enemies’, Musical Times 37 (1 May 1896): 309.

- Mrs George de Horne Vaizey, ‘A Houseful of Girls’, TGOP 22 (6 October 1900): 1.

- Kimberly Reynolds, Girls Only? Gender and Popular Children’s Fiction in Britain, 1880–1910 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990), 145, 147.

- Ibid., 147.

- Margaret Beetham, A Magazine of her Own? Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine, 1800–1914 (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 12–13.

- New Orleans native Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) and Swiss-born Sigismond Thalberg (1812–1871) were popular nineteenth-century composers and virtuoso pianists. See Grove Music Online, ed, Deane Root, Oxford University Press, accessed 1August 2015 at http://oxfordmusiconline.com.

- Huneker, 291–3. On the polemics of women as orchestral musicians and composers in America, see Judith Tick, ‘Passed Away Is the Piano Girl: Changes in American Musical Life, 1870–1900’, in Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150–1950, ed. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 325–48.