Personal Reflections on Coping with War

Part 7 When Patients Were in Crisis

For the 25 flight nurses interviewed for Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, wartime service was beset with potentially difficult circumstances that could exact a toll on even the most hardy of nurses. To cope with these professional and personal challenges, these women drew on many sources of support, tangible and intangible, physical and mental. Social support, one’s physical condition, and abilities and skills fostered in nurses’ training all helped the flight nurses cope behaviorally with the multiple demands of the war. Reasonable expectations, devotion to duty, an optimistic outlook, and faith in one’s God, one’s colleagues, and one’s self all helped them cope emotionally with the war.

Louise Anthony, a flight nurse with the 816 Medical Air Evacuation Squadron (MAES) in England, who made her first trip into Normandy on 15 June 1944 after D Day, flew over, as did other medical crews, in planes loaded with gasoline for Patton’s army. As the patients were brought on board the plane now configured for air evacuation, enemy shells were getting close, and an officer told the crew to shut the door and take off. Anthony saw that one of her patients was dying and, realizing that he might not survive the flight, tried to find someone to remove him from the plane. But it was too late – the ground crews had left. As soon as they were airborne, Anthony asked the radio operator to call for a doctor to meet the plane. When the patient died over the English Channel, Anthony successfully hid the fact from the other patients: “I did not cover his face, I turned his head, I adjusted his pillow, I checked his pulse, I pulled the blanket back to check his dressings – the same as all the rest of the patients. … And so no one knew anything.”

Toward the end of the war Dorothy White, assigned to the 807 MAES in the Mediterranean, transported a German POW with a sucking chest wound. Because of the extent of the wound, his breaths gasped out his back. He was “a horrible shade of gray” and needed oxygen, but the plane was not equipped for its use. White discovered that the crew chief had a tank of oxygen and a funnel, and, using a rectal tube as the connection, she held the apparatus to the patient’s face for three hours to give him some relief. The crew meanwhile radioed ahead for a physician to meet the plane at the airfield. When the British doctor came on board and saw White’s “fancy gadget,” he said, “I don’t believe it – American ingenuity!” The patient survived the flight thanks to White’s ability to improvise.

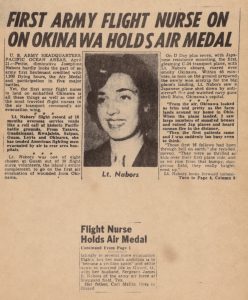

Jo Nabors of the 812 MAES volunteered to be the first flight nurse from her squadron to fly into Okinawa, never thinking that hers would be the first of eight names selected from a hat. The fourth day after the bombing had begun, she flew into the island to pick up a load of patients and was petrified, because she could see the devastation from the bombing and hear the firing. When the plane landed and the soldiers saw Nabors, they ran up and crowded around her, asking what she was doing there. “Don’t get out of the airplane, you’ll get shot,” they warned her. Nabors said to the flight surgeon on board, “My God! Get me out of here, because I don’t think it’s safe here. Even by our boys!” He replied, “You have a gun, don’t you? Just use it!” Twenty-four minutes later the patients were loaded and the flight was on its way. The plane was full with newly wounded patients en route to Guam, many of them double amputees. One patient was blind, and Nabors worried about him the most. Only eighteen years old, he had lied about his age. He did not want to go home, because he was afraid of what his family would say – he had no will to live. “They say nurses are hard,” Nabors commented, “but we aren’t hard. I cried and cried with that boy.” Nabors sensed that he was near death because of his despondency, and indeed he did die, not on her flight, but on his flight out of Guam.

Honolulu newspaper clipping [USAF Photo]

Honolulu newspaper clipping [USAF Photo]

Helena Ilic, assigned to the 801 MAES in the Pacific, summed up the flight nurses’ bond with their patients:

Well, I think that you owe your patients everything that you possibly can give them. You know, everything. Your knowledge. I think it is absolutely imperative to think of your patients’ comfort, safety, before you think of your own. … And I think that you owe your patients not knowledge just in treating them, but, like, feeding them – in every aspect. … I think resourcefulness is the word. That’s what you owe your patients, and not just the minimum care. And I think you owe your patients hope, and you owe your patients, I suppose, hope and cheerfulness. That’s very, very important.

Flight nurse and enlisted technician tend to litter patients

Flight nurse and enlisted technician tend to litter patients

on an air evacuation mission [Author’s Private Collection]