Eighth in a Series of Ten Blogs offering A Short History of Nursing from antiquity through the

mid-twentieth century. Part 1 – From Sacred to Secular – covers nursing in ancient

times through the Crimean War. Part 2 – From Civilian to Military – continues with

the establishment of the Saint Thomas School of Nursing through World War II.

A Short History of Nursing

Through World War II

Part 2 From Civilian to Military Nurses

The Spanish-American War and Second Anglo-Boer War

The Spanish-American War, ignited by an explosion aboard an American battleship in Cuba’s Havana Harbor in February 1898, lasted a mere four months ending in a U.S. victory with the acquisition of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. It was a victory of sorts for American military nursing as well, for after a hundred or so mostly untrained nurses were hired to care for soldiers afflicted by infectious diseases, a careful screening process led to a predominantly hospital-trained corps of nurses. The most formidable enemies of the war were not on the battlefields of Cuba and the Philippines but rather in military camps stateside and overseas where typhoid fever, yellow fever, dysentery, and malaria ran rampant.

As in past wars, military male orderlies provided nursing care for soldiers, but the U.S. Army Surgeon General was farsighted enough to recognize that, with the increased needs of the army medical department, use of trained women nurses would be a valuable asset. He authorized physician Anita Newcomb McGee, later appointed Acting Assistant Surgeon General of the Army, to chair a board to examine nurse candidates for military service. All nurses selected would have training in an established hospital school of nursing, making this war the first in the American military to employ an all-graduate corps of nurses for the army and the navy – in theory if not in practice. McGee also established the chief nurse designation, equivalent to the superintendent of nurses in a civilian hospital, to whom nurses reported rather than to the medical staff. But the increased demand for nurses in the camps as well as in general hospitals during the raging epidemics required that McGee lower her standards of eligibility set to dispel the notion of army nurses as amateur volunteers. 1 Initially reluctant, as in past wars, to work with women nurses, military medical staffs underwent a “sea change” in their attitude toward these nurses. Chief surgeon Colonel John Van Renessler Hoff at a military camp in Georgia, for instance, told chief nurse Anna Maxwell, “When you first arrived we did not know what to do with a contingent of women in the camp; now we are wondering what we should have done without you.” 2

A similar change in attitude about nurses was needed during the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) fought in South Africa between Britain and two independent Boer states, sparked by a build-up of British forces in the region; gold deposits were at its root. Caroline Adams notes, “Nursing in the Second Anglo-Boer War can be seen as something of a watershed in modern military nursing. It was in the theatre of war that nurses would carve out a meaningful role for themselves as skilled primary care givers in military hospitals, after consolidating their position against challengers.” 3 Nurses and amateurs who arrived in South Africa as though they were entering society rather than a nursing ward, minimally trained male soldier orderlies who provided the majority of nursing care, and doctors who favored these orderlies over the trained female nurses were the challengers of the current war.

The Second Anglo-Boer War shared similarities to the American war recently ended: imperialism was a factor in each; disease proved more deadly than combat; women continued to face the reluctance of some medical men to recognize their place in stationary and field hospitals; and women eventually demonstrated their value and secured their place as military nurses. Lessons learned in both wars included the need for a reserve of female military nurses for mobilization in time of war to provide adequate staffing of military hospitals.

The male orderlies, who were soldiers first and nursing personnel second, could be rude and unwilling to take orders from the nurses who held no rank and thus had no authority or power over them. The nurses were in the military but not of the military, since they had no standing in the military chain of command. Not until World War I did military nurses achieve officer status in the form of relative rank; actual rank was not given to nurses until World War II. Adams notes the irony of the situation: “Nightingale’s work associated with the war in the Crimea was a vital catalyst to the emergence of modern nursing. Yet it was in the military sphere that modern female nursing was most lacking.” 4

To learn how the history of nursing was reflected on the opera stage, see Judith Barger, The Nurse in History and Opera: From Servant to Sister (Lexington Books, 2024).

Notes

- Mercedes H. Graf, “Women Nurses in the Spanish-American War,” Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military 19 (1) (Spring 2001), ProQuest; Yoshiya Makita, “Professional Angels at War: The United States Army Nursing Service and Changing Ideals of Nursing at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Japanese Journal of American Studies 24 (2013): 70–74.

- Gary Goldenberg, Nurses of a Different Stripe: A History of the Columbia University School of Nursing 1892–1902 (New York: Columbia University School of Nursing, 1922), 49.

- Caroline Adams, “Lads and Ladies, Contenders on the Ward – How Trained Nurses became Primary Caregivers to Soldiers during the Second Anglo-Boer War,” Social History of Medicine 31 (3) (August 2018): 555.

- Ibid., 561.

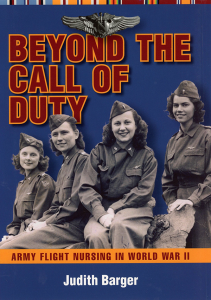

Featured Image:

the-australian-national-maritime-museum-9cHrXOvbj38-unsplash.jpg