Organ Benches and Bicycle Seats:

Pedalists in Victorian England

Part 1 Organ Benches

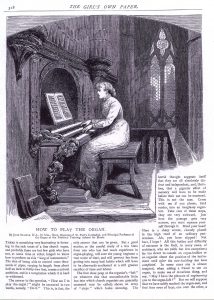

In a 1927 retrospective account of organs and organists, Charles Pearce, then Vice President of the Royal College of Organists, wrote that ‘The evolution of pedal playing in England was as slow as the progress of the pedal organ itself. Old fashioned organists were such skilful left hand players that it took time to convince them of any necessity for playing with their feet.’ 1 Samuel Wesley was apparently among those organists who needed convincing, because he is reported to have conceded that ‘pedals might be of service to those who could not use their fingers’. 2

Fifteen years after Wesley’s death some organists still relied on their hands, not their feet, when playing. The story is told of Sir George Smart, who, when asked as one of the musical judges to try one of the pedal organs on display at the Great Exhibition of 1851, replied contemptuously, ‘My dear Sir, I have never in my life played upon a gridiron.’ 3 And this from the organist who had played for two coronations.

William T. Best, long-time organist of Saint George’s Hall, Liverpool, headed Pearce’s list of ‘brilliant pedalists’, with Frederick Archer, Alexandre Guilmant, John Stainer and William Hoyte rounding out the top five. 4 Missing from Pearce’s list was Felix Mendelssohn, who, in his organ recitals in England, was known to execute ‘a storm of pedal passages with transcendent skill and energy’ in his performance of the Bach Fugue in A Minor. 5

Nor do any women organists appear among the ranks of brilliant pedalists, although, if reviews of recitals are an indication, some of these women performers deserved to be on Pearce’s list. For example, in an account of organ recitals in nineteenth-century England, an anonymous author recalled that Elizabeth Stirling, who was best known for her part song ‘All among the Barley’, was ‘all among the pedals’ in recitals when just a teenager. 6 In August 1837 at age eighteen, Stirling had given her first known recital, at Saint Katherine’s Church, Regent’s Park, London. Her performance, which lasted over two hours, featured eleven of Bach’s major organ works, as well as three pieces by other composers. 7

At the time of Stirling’s debut, organ recitals were heard in England in organ manufactories and in concert locations such as Exeter Hall. Organ solos were heard as part of recitals featuring vocal and instrumental selections. But to play an entire solo recital devoted almost exclusively to the works of Bach was an innovative approach to concert giving. Through the tireless efforts of Samuel Wesley, Benjamin Jacob, Carl Friedrich Horn and other enthusiasts, some of Bach’s organ music had been performed and published in London early in the nineteenth century. But the championing of Bach’s organ music was a bold venture given the status of English organs at the time. Organ pedals, if they existed, were used as assistance to manuals, for pedal points and other sustained notes and at cadences. The development of independent multi-rank pedal divisions did not occur in England until the second quarter of the nineteenth century. And not all organs had pedalboards conducive to performance of Bach’s obbligato pedal lines. 8 Thus organ pedaling was a novelty that did not escape the notice of the musical press – especially when it was performed by the feet of a young woman organist.

Stirling’s mentor Edward Holmes, who reviewed her recital at Saint Katherine’s for the Atlas, focused on the young organist’s command of the music of Bach and the pedals. He noted that her system of pedal playing, ‘which we believe is peculiar to herself, enables her to preserve a graceful and quiet seat at the instrument.’ Holmes added that ‘it might well be a matter of surprise that throughout the performance there was scarcely an error, or slip worthy [of] notice’. 9 His surprise at Stirling’s nearly flawless pedaling suggests a standard new to England by which an organist’s skill would be judged.

When Stirling played her second recital a few months later, at Saint Sepulchre Church Holborn, and played ten of Bach’s major organ works, the reviewer for the Musical World reprinted the program as ‘the first decided exhibition of a lady pedal player’. 10 Reviewers were particularly impressed by her management of pedal sequences that ‘however harassing and difficult, are executed by her with the utmost certainty and without the slightest apparent effort’. 11

Stirling returned to Saint Sepulchre in July 1838 for yet another recital featuring the music of Bach. In its review of the recital the Musical World expressed surprise at seeing the trios of Bach attempted, ‘and by a lady’. The review continued: ‘Mr Wesley lived to enjoy the fruits of his zeal for Bach and his writings in the rise of a perfect army of pedal players, and the legitimate performance of the trios by one of his pupils.’ 12 It was perhaps because Stirling had used Wesley’s edition of the trio sonatas that the reviewer forged the link between the veteran Wesley and the new recruit, Stirling. Use of the military analogy was apt, because organ pedaling was thought – by men – to require a great deal of physical stamina.

Stirling was not the only woman organ recitalist in Victorian England, though she was the only one whose recitals were publicised in the first half of the century. Between 1850 and 1896 at least thirty-three women organists are mentioned by name in music journals and newspapers in recitals in churches, schools, institutes and exhibitions. Their acceptance in this role, however, was not free of pundits who cast doubts on women’s fitness – social, medical and musical – to master the complexities of the organ and its pedals.

An example is found in two recitals, both reviewed in the Musical Standard, in which organist Theresa Beney performed Bach’s Toccata in F Major. The tone of the first review was positive. Still of the belief in 1879 that ‘an organ recital by a lady is somewhat of a novelty’, the critic congratulated the courage of Beney, who was apparently a bit nervous, and noted that her execution of the Toccata ‘proves that good pedal-playing is not out of the range of a well-taught lady’. 13 Beney, who studied at the National Training School for Music, was a pupil of J. Frederick Bridge, organist of Westminster Abbey.

A repeat performance of the piece by Beney in 1883 prompted the reviewer, addressing the skeptics, to note that ‘the aptitude for a lady for pedal playing was admirably illustrated’. This may have swayed some of the journal’s readers, but the critic himself was not yet fully convinced. He began positively:

Although one does not like the notion of a lady struggling with a big organ and engaged in work so trying and requiring such courage and watchful power as recital playing, save in rare instances, it must be acknowledged that ladies can play the organ, and as pedalists are exceedingly neat and sure-footed, possibly by reason of incessant practice measuring distances by their feet without being able, as men are in walking and pedal-playing, to watch their pedal movements. 14

An underlying bias against women organists then surfaced, though the critic implied that his view was not widely held and might be an unpopular one: ‘On the other hand, the power and grandeur of a large organ would seem to be best handled by the sterner strength of the “lords of creation,” to say nothing of questions of mental power, which the writer will not venture upon, lest his opinions bring him into hot water.’ 15

He likely was alluding to society’s long-held belief in the innate intellectual and physical inferiority of women compared to men, based in part on smaller size of brain and body. When women began to demand equal opportunities of education and employment in the second half of the nineteenth century, this belief provided the justification that men sought to curtail women’s activity outside the home. Basically, men argued that to expend what was understood at the time as the body’s finite amount of energy on these ‘needless’ pursuits would rob women of the vital energy needed to keep their reproductive organs functioning properly. Women who failed to pay attention to their special ‘periodicity’ would become ill and unable to bear children – or so men claimed.

The ‘lords of creation’ – to use the critic’s words – had for the most part managed to keep women off the organ bench by perpetuating the notion that women’s place was in the home and out of the public eye. But Victorian sources detailing woman’s role in society – conduct books, advice manuals, periodicals and even fiction – were more prescriptive than descriptive. Female organists are a case in point.

Beginning in 1895 another woman organist, Emily Edroff, who was associated with the London Organ School first as a student and then as a professor, was dazzling her audiences with performances of Widor’s Toccata form the Fifth Symphony. Her ability as a pedalist was not mentioned in recital reviews, however. What had changed?

Notes

1. Charles Pearce, The Evolution of the Pedal Organ and Matters Connected Therewith (London: Office of ‘Musical Opinion’, 1927), 57.

2 ‘In resuming our consideration’, Musical World 13 (21 May 1840): 315.

3 Pearce, Evolution of the Pedal Organ, 57.

4 Ibid., 68.

5 ‘Mendelssohn as an Organist’, Musical World 7 (15 Sep 1837): 79.

6 ‘The Organ Recital: A Contribution Towards Its History’, Musical Times 40 (1 Sep 1899): 602.

7 Edward Holmes, ‘Organ Performance at St. Katherine’s Church, Regent’s Park’, Atlas 12 (20 Aug 1837): 538.

8 James Boeringer, Organ Britannica: Organs of Great Britain 1660–1860, vol. 1 (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 1983), 45.

9 Holmes, ‘Organ Performance at St. Katherine’s’, 538.

10 ‘Concerto Organ Performance’, Musical World 9 (26 Jul 1838): 209.

11 ‘Organ Performance at St. Sepulchre’s’, Musical World 7 (31 Oct 1837): 79; Henry Chorley, ‘Our Weekly Gossip’, Athenaeum, no. 521 (21 Oct 1837): 771.

12 ‘Concerto Organ Performance’, 208.

13 ‘Lancaster Hall, Notting Hill’, Musical Standard 3rd ser., 19 (27 Nov 1880): 344.

14 ‘Bow and Bromley Institute’, Musical Standard 4th ser., 24 (7 Apr 1883): 215.

15 Ibid.

To be continued