Women Organists in Victorian England:

What Did They Wear?

After I had presented a paper about women organists in nineteenth-century England at an organ conference in Oxford, England several years ago, a delegate approached me to ask, ‘But what did they wear?’ A good question for which we have little photographic evidence. We do, however, have illustrations and textual references that, when studied together, give an idea of how women organists confined to Victorian fashion dressed for the bench.

Today’s women organists have more socially acceptable options than did their Victorian predecessors for dressing to facilitate movement of the hands between the manual keyboards and easy foot access to the pedal board unencumbered by superfluous fabric. Women’s fashions in Victorian England were marked by their excess – tight-fitting bodices and voluminous skirts that accented a tiny waist cinched in by a tightly laced corset, and ostentatious display of ruffles, flounces and other embellishments to the clothing. Skirts were long, falling below the ankle. The addition of more and more heavy petticoats or crinolines to fill out the silhouette gave way to the hoop skirt supported underneath by a lightweight, cage-like foundation of steel rings and fabric tape secured around the waist. The copious fabric of the skirt eventually found its way swept to the back, and hoops gave way to a padded bustle.

Obviously, such fashions did not sit well on a church organ bench. Thus, how to dress was a concern for women organists. Not only propriety, but also practicality determined the women organists’ attire. If the organ was located in or near the chancel of the sanctuary, the organist could be in full or partial view of the congregation in the nave. Although organs located in a church’s galley were above the congregation’s line of sight and partially hidden, stairwells to organ lofts could be narrow and steep, and organs often were fit into tight spaces. Unlike the piano stool, the organ bench had to allow optimum movement of the feet on the pedal board. Even if a woman could pedal accurately without looking at her feet, the folds of a long, full skirt could get in the way.

Victorian women were held to a high standard of decorum, especially in church, and Victorian men were not hesitant to air their views about a lady organist’s appearance.

The issue of how a woman should dress for church was a highly contested one when it came to their visibility as choristers in mixed choirs in Anglican churches in the last half of the nineteenth century. When in August 1889 correspondent Musicus asked the readers of the Daily Telegraph what objection there might be to a mixed choir of ladies and gentlemen, he received an immediate, overwhelming response, with the focus of letters shifting from how lady choristers should be attired to whether they should be choir members at all. Claiming the topic ‘much ado about nothing’, the newspaper, which came out in favour of lady choristers, printed ninety-two of the hundreds of letters it received daily over a two-week period.

For a full discussion of this issue, see ‘Silenced Voices: Female Choristers in Nineteenth-Century England’ on this website. From the Toolbar, click on Books > Elizabeth Stirling > Book Extras. Or click on this link:

https://judithbarger.com/books/elizabeth-stirling/book-extras/

Correspondents weighed in about the attire for lady organists as well. Like the debate about lady choristers, the issue cloaked the greater concern about whether women should be organists at all. Writing to the Musical World in 1857, correspondent Pedal who declared the organ ‘by no means a lady’s instrument’, explained: ‘Their very dress is against them, since it impedes their pedaling.’ 1 Not only was the act of raising one’s skirt a foot or so to facilitate pedaling unbecoming and immodest, he claimed, the positions necessary to play the pedals were extremely indelicate, if not indecent. ‘No female but a Bloomer should be an organist,’ he stated, referring to the baggy ankle-length trousers worn beneath a loose knee-length tunic made popular by American Amelia Bloomer in the 1850s. 2 Any woman who would wear such a costume, according to Pedal, was sufficiently masculine to be an organist but, because her femininity was then suspect, had consequently lost her respectability. When the topic had run its course, the Musical World’s editor chastised Pedal’s immodest thoughts in church concerning a lady’s exposed ankles. 3

The matter of whether one should look at one’s feet when playing the organ was not exclusive to lady organists but also provided a target of opportunity for correspondents to chide their brother organists. Writing to the Musical Standard in 1863, Manuals joined the debate that had resurfaced about lady organists’ suitability for church positions and used the issue of pedal playing to lend his support in their favour. Many women organists played badly, he said, but many men organists played badly too. Believing that skill, not sex, should determine competency as an organist, Manuals asked, ‘What is there, either intellectually or physically to prevent ladies playing as efficiently as the opposite sex?’ 4 He used pedal playing as an example: Many men had to see the pedals before they could play them, but women, whose crinolines distended their skirts and concealed the pedals, played them correctly. 5 Correspondent W. C. Filby put it more succinctly: ‘As to pedalling, a lady cannot look at her feet – a gentleman ought not look at his.’ 6

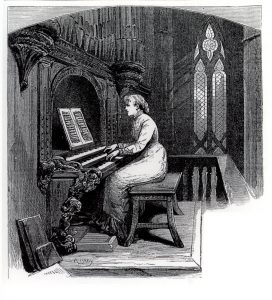

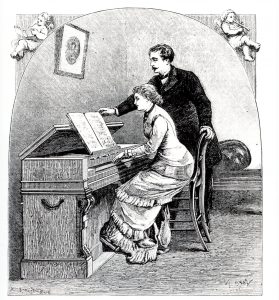

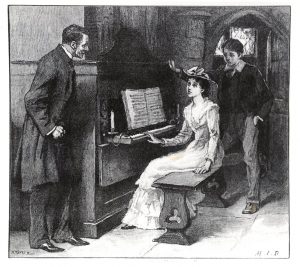

Several drawings in the popular girls’ magazine, The Girl’s Own Paper, published in London by the Religious Tract Society beginning in 1880, offer a glimpse of what a young woman might have worn when playing the organ in the last decades of the nineteenth century. In each drawing, shown below, she is dressed in feminine clothing that is modest, yet tasteful. Without being slaves to fashion that would impede their position at the console, female organists could dress appropriately, avoiding bloomers, divided skirts and other ‘scandalous’ clothing considered by men as improper attire for women.

John Stainer, ‘How to Play the Organ’, The Girl’s Own Paper 1 (22 May 1880): 328. [Lutterworth Press]

John Stainer, ‘How to Play the Organ’, The Girl’s Own Paper 1 (22 May 1880): 328. [Lutterworth Press]

King Hall, ‘How to Play the Harmonium’, The Girl’s Own Paper 1 (24 Jul 1880): 472. [Lutterworth Press]

King Hall, ‘How to Play the Harmonium’, The Girl’s Own Paper 1 (24 Jul 1880): 472. [Lutterworth Press]

‘Notices of New Music’, The Girl’s Own Paper 9 (17 Dec 1887): 177.

‘Notices of New Music’, The Girl’s Own Paper 9 (17 Dec 1887): 177.

[Lutterworth Press]

Ada M. Trotter, ‘Marsh Marigolds’, The Girl’s Own Paper 16 (3 Nov 1894): 65.

Ada M. Trotter, ‘Marsh Marigolds’, The Girl’s Own Paper 16 (3 Nov 1894): 65.

[Lutterworth Press]

The Church Musician in 1895 offered its view on proper dress for women organists, probably with an eye to the recent controversy concerning lady choristers’ attire:

A lady asks what dress she should wear when playing the organ in church? Her ordinary quiet, ladylike costume, of course, attracting as little attention as possible. Any attempt at college caps, gowns, surplices, &c. for her sex are simply fads of modern lunatics, unknown till yesterday in the Catholic church. 7

Shoes as well as dress would have been chosen carefully for organ pedaling. Writing to the Church Musician in 1894 to ask what forms of shoes his brother organists found convenient to wear when playing the organ, George Stanton implied that female organists might have the same concern. Organists’ footwear varied, Stanton wrote. ‘Each has his or her own taste, and every organist wears the boot which suits him best. I know some players who wear laced boots; some who prefer elastic sides; some who wear slippers, rubber-soled shoes, or anything else which suits their individual fancy.’ 8 His inquiry received no replies in the journal’s columns. No illustration accompanied a Musical Times advertisement in 1870 for ‘Flexura, or Patent Steel Spring Waist Boots, particularly adapted for Organists’ to show a type of shoe worn by nineteenth-century organists. 9

When Theresa Beney, who had attended the National Training School for Music on an organ scholarship, gave her first recital at Bow and Bromley Institute in March 1883, the reviewer for the Musical Standard felt it necessary to debunk the still prevalent notion that ladies were not up to the task of mastering the pipe organ. He, like others before him, used pedaling to make his point:

The popular notion that ladies do not succeed entirely as organ players, would be considerably disturbed in the minds of those entertaining the idea who chanced to be present at the recital of March 31st. Although one does not like the notion of a lady struggling with a big organ and engaged in work so trying and requiring such courage and watchful power as recital playing, save in rare instances, perhaps, it must be acknowledged that ladies can play the organ, and as pedalists are exceedingly neat and sure-footed, possibly by reason of incessant practice in measuring distances by their feet without being able, as men are in walking and pedal-playing to watch their pedal movements.

The reviewer, like many of his brother organists, still was not convinced that ladies belonged on the organ bench, for he concluded: ‘On the other hand, the power and grandeur of a large organ would seem to be best handled by the sterner strength of the ‘lords of creation,’ to say nothing of questions of mental power, which the writer will not venture upon, lest his opinions bring him into ‘hot water.’ 10

For an in-depth discussion of the ‘eligibility’ of women to serve as organists in nineteenth-century Anglican churches, see Elizabeth Stirling and the Musical Life of Female Organists in Nineteenth-Century England (Ashgate 2005). The book currently is out of print but may be found in libraries and purchased from used booksellers.

Notes

1 Pedal, ‘No Lady Need Apply’ [correspondence], Musical World 35 (12 Sep 1857): 585.

2 Ibid.

3 ‘Really, some of our organists’, Musical World 35 (12 Sep 1857): 588.

4 Manuals, ‘Male and Female Organists’ [correspondence], Musical Standard o.s. 1 (1863): 274.

5 Ibid., 274 – 75.

6 W.C. [William Charles] Filby, ‘Male and Female Organists’ [correspondence], Musical Standard o.s. 1 (1863): 274.

7 ‘A lady asks’, Church Musician 5 (1895): 2.

8 George A. Stanton, ‘Organists’ Shoes’, Church Musician 4 (1894): 155.

9 ‘Flexura, or Patent Steel Spring Waist Boots’, Musical Times 14 (1870): 582.

10 ‘Bow and Bromley Institute’, Musical Standard 24 (7 Apr 1883): 215.