Ninth in a Series of Ten Blogs offering A Short History of Nursing from antiquity through the

mid-twentieth century. Part 1 – From Sacred to Secular – covers nursing in ancient

times through the Crimean War. Part 2 – From Civilian to Military – continues with

the establishment of the Saint Thomas School of Nursing through World War II.

A Short History of Nursing

Through World War II

Part 2 From Civilian to Military Nurses

World War I

Not until World War I did military nurses achieve officer status in the form of relative rank; actual rank was not given to nurses until World War II. Adams notes the irony of the situation: “Nightingale’s work associated with the war in the Crimea was a vital catalyst to the emergence of modern nursing. Yet it was in the military sphere that modern female nursing was most lacking.” 1

The Army Medical Department saw women in the Army Nursing Service, who were employed only in a supervisory capacity, as interfering civilians rather than as military assets; most of the actual nursing was left to untrained orderlies as “Sarah Gamp, in male attire,” leaving the sisters’ status ill-defined. 2 Fortunately, civilian doctors who volunteered for wartime service and had worked with civilian nursing sisters were more open-minded. To Eleanor Laurence, working as a nurse in South Africa was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

I would not have missed nursing through this war for a great deal. We have often had rough times, and anxious times, and of course I have not been able to do much, but I have been able to help a few men to recover their health and strength; and, perhaps, also to help a few in their last hours, men whose own relations would have given much to have been in my place. 3

Even as the war raged in South Africa, nurse leaders in Britain, its colonies, and the United States were waging their own battle for mandatory nursing licensure to protect both the profession and the public from amateurs posing as trained nurses – a situation exacerbated in wartime. A nursing license would assure civilian and military employers that its owner possessed a minimum level of competency. It was a prolonged battle not concluded until after World War II when mandatory nursing licensure following standardized education and certification by a nationally recognized examining body became a requirement to practice as a registered nurse. The passage of the legislation was a significant accomplishment at a time when women were disenfranchised and thus held little political power. Although not yet given the right to vote, nurses had taken control of their profession into their own hands.

A little over a decade after the Second Anglo-Boer War ended in British victory in May 1902, the military medical departments of Britain and the United States found themselves short of the number of nurses needed to staff Allied hospitals in France, which had become the battleground of World War I after the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne in June 1914. While the United States remained neutral, the American Red Cross mobilized its medical resources to have entire hospital units staffed with nurses as well as doctors ready to travel to France. In the meantime, nurses traveled on their own to Europe to assist wherever their services would be welcomed. Their eagerness to be part of the war effort is captured well in correspondence and articles submitted to the American Journal of Nursing (AJN). 4

According to Anne Summers, “The history of British army nursing between the Boer War and 1914 is essentially the history of nursing reserves.” 5 The same could be said for the United States Army: both countries used the years of relative peace to insure that properly trained and qualified nurses would be available for the military in event of a future war. In Britain, Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) began their training in 1909, and their numbers far exceeded those for reserve nurses.

The use of VADs in World War I hospitals was controversial. At a time when nurses sought recognition as members of a profession that demanded a higher entry level assured by standardized training, examination, certification, and registration, amateurs were assigned to hospital nursing work after only a few months’ training in first aid and home nursing. What in theory prepared VADs for work at military rest stations and on hospital trains, with emphasis on meal preparation, in practice, due to a shortage of nurses, expanded to include actual nursing of sick and wounded soldiers. 6 That the VAD uniforms were similar to those worn by nurses, and that the patients called the VADs “nurse” or “sister” muddled the distinction between the two levels of nursing preparation.

Mary Burr took those who administered VAD training to task. Her indignation was not with the VADs themselves, but rather with the system that lowered the standards for nursing care providers in light of the national emergency. Burr vented her frustration at the unforeseen “fruits” of nursing’s ten-year fight for registration, “that the up-building of the education of nurses should be ruthlessly wrecked and cast aside at the first opportunity.” She found it “heartbreaking” that nurses’ work had been minimized: “Had we been given registration and allowed to organize our profession on just lines, how different the war nursing would have been! Then there would have been a place for everyone and everyone in her place and untrained duchesses would not have been running ambulances while trained nurses waited for permission to nurse.” 7

Like Britain in the early twentieth century, the United States built up its reserve of nurses as a contingency for possible future war. Reforms in the War Department led to formation of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and Navy Nurse Corps in 1908. In 1905 the American Red Cross (ARC) developed a nursing service and enrolled nurses for mobilization in time of emergency. In 1911 American President William Howard Taft designated the ARC Nursing Service as the reserve for the Army Nurse Corps and Navy Nurse Corps from which nurses would be assigned to the military as the need arose. 8

Neither the United States nor Britain ever filled its quota of nurses needed for wartime service. Nurses’ aides and VADs helped fill the gap. Because demand for nurses far exceeded supply throughout the war, nursing leaders and concerned journalists took up the cause in press appeals targeted at nurses. 9 AJN printed numerous articles about nurses in military hospitals both stateside and overseas and for those nurses contemplating active service. Although Alice Fitzgerald was concerned that she might have “painted the picture in tones too dark,” an anonymous contributor to Literary Digest was more blunt stating that “without a significant number of trained nurses, America’s young men will languish and die. This will have the effect of prolonging the war, and thus robbing the country of thousands of men who otherwise might not have to be sacrificed.” 10

The spirit of optimism and adventure reflected by Wormeley in the Civil War reasserted itself in the nurses of World War I, evident in letters that Julia Stimson, chief nurse at an ARC hospital in St. Louis, wrote to her parents as she crossed the Atlantic to assume the same position overseas. Her reassurance sounds very much like Wormeley’s own enthusiasm fifty years prior. “Don’t you worry about me one least little bit,” Stimson wrote. “I am having the time of my life and wouldn’t have missed it for anything in the world.” 11 When she arrived in France three months later, Stimson’s ardor had not dampened: “You must not think I am doing anything but exactly what I wanted most to do, and there is no heroism in that.” 12 Stimson was not alone in her desire to be where the action was in wartime Europe.

America’s entrance into the war in 1917 changed its course. Weakened by loss of manpower and supplies and threatened with imminent invasion, Germany signed an armistice on 11 November 1918, ending the Great War. On return to the United States, Helen Boylston, a nurse with the ARC Harvard Medical Unit in France, was homesick for “the old days” in France. “How we worked!” she reminisced. “We gave all we had to give, and life was glorious. Even numbed with fatigue as we were, we knew it was glorious.” 13 The nurse could leave the battle, but the battle, it seems, could not leave her alone. Nurses’ next battles were back home in England and the United States for nursing registration to protect their title and to assure properly trained and fully qualified nurses for civilian and military work; for the right to vote, based in part on their crucial service to and in the military during the war just ended; and, for military nurses, rank and status of commissioned officers that would place them in the chain of command with authority to give orders to and expect obedience from orderlies regarding patient care.

As had been the case after previous wars, once the armistice was signed, the nurse corps of the various services were demobilized and scaled back to peacetime levels, giving nursing leaders the opportunity to rescind the lowered entry standards that World War I had necessitated to meet the nursing shortage. Yet the Treaty of Versailles had crafted a precarious peace. When Adolf Hitler invaded Poland with his rearmed German army in September 1939, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany, and World War II began. The United States entered the war in December 1941 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

To learn how the history of nursing was reflected on the opera stage, see Judith Barger, The Nurse in History and Opera: From Servant to Sister (Lexington Books, 2024).

Notes

- Caroline Adams, “Lads and Ladies, Contenders on the Ward – How Trained Nurses became Primary Caregivers to Soldiers during the Second Anglo-Boer War,” Social History of Medicine 31 (3) (August 2018): 561.

- Francis E. Fremantle, Impressions of a Doctor in Khaki (London: Murray, 1901), 444.

- E. [Eleanor] C. Laurence, A Nurse’s Life in War and Peace (London: Smith, Elder, 1912), 311.

- See, for instance, K. K. and M.E.H., “Experiences in the American Ambulance Hospital, Neuilly, France,” American Journal of Nursing [AJN] 7 (15) (April 1915): 549. An ambulance hospital is a military hospital in France.

- Anne Summers, “Women as Voluntary and Professional Military Nurses in Great Britain, 1854-1914” (Ph.D. thesis, The Open University, 1986), 311.

- Mary Burr, “The English Voluntary Aid Detachments,” AJN 15 (6) (March 1915): 463–64.

- Ibid., 467.

- Katherine Burger Johnson, “Called to Serve: American Nurses go to War, 1914–1918” (M.A. thesis, University of Louisville [KY], 1993), 25.

- See [Sophia Palmer], “Editorial Comment: Are We Slackers?” AJN 18 (4) (January 1918: 283–84; [Sophia Palmer], “Editorial Comment: The Nurse’s Privilege” and “What to Do,” AJN 18 (6) (March 1918): 441–44; Dorothy Foster, “Nurses, Join Now!” AJN 18 (8) (May 1918): 610–12.

- Alice Fitzgerald, “To Nurses Preparing for Active Service,” AJN 18 (3) (December 1917): 191; “A Call for Women to Volunteer,” Literary Digest, 22 June 1918, 30.

- Julia C. Stimson, Finding Themselves: The Letters of an American Army Chief Nurse in a British Hospital in France (New York: Macmillan, 1927), 13.

- Ibid., 106.

- Helen Dore Boylston, “Sister”: The War Diary of a Nurse (New York: Washburn, 1927), 199, 200–201.

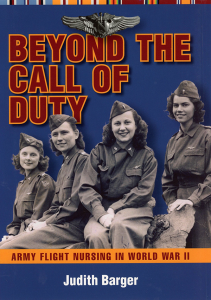

Featured Image:

the-australian-national-maritime-museum-9cHrXOvbj38-unsplash.jpg