Personal Reflections on Coping with War

Part 9 When Missions Went Awry

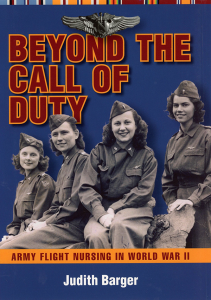

For the 25 flight nurses interviewed for Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, wartime service was beset with potentially difficult circumstances that could exact a toll on even the most hardy of nurses. To cope with these professional and personal challenges, these women drew on many sources of support, tangible and intangible, physical and mental. Social support, one’s physical condition, and abilities and skills fostered in nurses’ training all helped the flight nurses cope behaviorally with the multiple demands of the war. Reasonable expectations, devotion to duty, an optimistic outlook, and faith in one’s God, one’s colleagues, and one’s self all helped them cope emotionally with the war.

Potential aircraft emergencies were not uncommon on many air evacuation missions. The possibility of ditching at sea was foremost in many flight nurses’ thoughts, since so much of their flying was over water. Jocie French, who flew with the 818 MAES in Europe, wished she had remembered more from her survival training in flight nurse school when she had to don a parachute as a precautionary measure. “I kept thinking, Do I get out of this parachute before we hit the water … or do I hit the water with the parachute?”

Denny Nagle, who flew with the 815 MAES in Europe, recalled a flight with a full load of patients during which the plane lost one of its engines. ”I was thinking what we were going to do when we go down in that zero [degree] water down there.” The flight nurses had been told that a person could survive only for twenty minutes in such cold water, she said. “You didn’t have a chance. But you’d think, Can you get them out of here? And what can you do if you do?”

“Dingie” Life Raft Instructions

815 MAES Flight Surgeon Captain Wormsley

[Author’s Private Collection]

Flights with patients on board exacted fortitude that at times conflicted with a flight nurse’s natural instincts. Jo Nabors, assigned to the 812 MAES, recalled a flight into a Pacific island where the harbor was being bombed. “They were shooting at us. … I was panicky. And when we landed, and we got our load of patients and started back out, I was never so glad to leave an island as I was that day.” Despite her panic, Nabors appeared cool and calm to her patients, telling little jokes. When the plane ascended to get out of the range of ack-ack, a patient with an open chest wound began bleeding. Nabors thought, “Oh, what’ll I do, what’ll I do?” She gave him morphine for his pain, administered oxygen, and re-plugged the chest wound to stop the bleeding. “Any emergency that comes up, you have to do it. Well, all I could think of was if we were shot down. … I was deathly afraid that I would have to ditch first, and then save myself, and then try to save all these boys.”

Nabors struggled with the expectation that in the event of an emergency her safety came before that of her patients. She was more valuable than her patients, her commander had said, and unless she and the rest of the crew saved themselves, they would not be able to help the others. “I had to get out of the plane first,” Nabors stated. ”And that’s where I felt that sometimes that it was a little bit difficult to make a decision. How could you make a decision like that?” On one occasion, when her plane lost a propeller, Nabors had to prepare her patients to ditch. The plane landed safely on land, but Nabors had already made up her mind about what she would do. She had planned to shove all her able-bodied patients out the door first, throw a raft down, and then leave the plane herself. As she told her commander afterward, with the water and waves so high in the Pacific, she could never open the raft herself at five-feet-two-inches tall and weighing only 102 pounds. He replied, “Well, the good Lord has to be looking out for you.” Nabors said, “Yes, plus my rosary beads.” It was a standing joke – Nabors always had her rosary beads with her.

Blanche Solomon, a flight nurse with first the 822 MAES, then the 830 MAES, was stationed at Harmon Field Newfoundland between May and September 1944, then at Lajes Field in the Azores and finally at Orly Field near Paris, June through October 1945. Much of her flying was between the Azores and Newfoundland. On a mission with a planeload of patients, one of them in a body cast, Solomon worried about that patient during a bad storm. The flight had passed the point of no return, and she wondered what she would do about him, should the plane have to ditch at sea. She explained: “We were taught that in case we were going down, and we knew we were going down, and if there was a patient that couldn’t be moved into one of the rafts, just to overdose him with morphine.” The plane landed safely with fifteen minutes worth of gas left.

On another flight Solomon had at least three blind patients, two in litter tiers, and one whose litter was on the floor of the plane. This last one concerned her most. He had lost his eyes as a result of combat wounds, and Solomon had to irrigate his eye sockets fairly frequently. On an earlier leg, the wheels on the plane’s landing gear had not rolled properly, but the plane had been taken up and tested without the patients on board, and everything seemed to be working fine. Yet there was still a chance that the wheels would not roll when they landed. So Solomon informed the patients about the situation and told the blind patients in the litter tiers that she would yell a warning just before the plane hit the ground so they could hold onto their litters. When she told the blind patient on the floor, she almost wept when he said, “Lieutenant, when you leave me, tell me you’re going so I’m not left talking to myself, because the nurse in the hospital did that, and I was talking for the longest time.” As they were getting ready to land, Solomon yelled, “Okay, hang on tight, and you’ll know when you’re rolling.” She sat on the floor next to the blind patient, because he was scared. The wheels rolled, Solomon said. “And we all breathed a sigh of relief.”