The Twentieth in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

The 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS Call Hawaii Home

Activated July 1943 and September 1943

Military historians Mae Link and Hubert Coleman note that “Long-distance air evacuation in the Pacific Area was begun on a large scale in November and December 1943 with the arrival of the 809th and 812th Medical Air Evacuation Squadrons (MAES).” 1 The 809 MAETS departed Bowman Field, KY for Hickam Field, Oahu in November 1943. Unlike previous squadrons, they traveled by air to Hamilton Field, CA where the squadron was attached to ATC and 5 ATC C–54s assigned to the squadron for air evacuation use. Squadron personnel were divided into 5 groups and flew on those planes to Hickam Field. The 809 MAETS was only the second squadron to have aircraft assigned specifically for air evacuation use; the 803 MAETS in the CBI had designated aircraft as well.

On arrival at Hickam Field, one Flight of the 809 MAETS was sent to Canton Island, a staging point for attacks on the Japanese–held Gilbert Islands. Another flight minus its flight nurses – for whom quarters at the location were inadequate – was sent to Funafuti on the Tuvala island in the west–central Pacific. The other two Flights remained at Hickam Field.

The 809 MAETS had been overseas just over 6 weeks and had not yet started flying air evacuation missions when the 812 MAETS arrived at Hickam Field. The 2 squadrons shared a Personnel Office, though their Headquarters and Operations remained separate. Air evacuation activities were shared between the 2 squadrons and their associated reports consolidated; the combined squadrons flew their first air evacuation missions that month. 2 The next month flight nurses at Hickam Field began making flights from Oahu to other islands in the Hawaiian Group, with the 2 squadrons’ nurses alternating day by day. 3 When adequate quarters for flight nurses were available on Tarawa, the station at Canton was closed, and in February MAETS personnel plus its flight nurses moved to Tarawa.

In May 1943 the contingent of the 809 MAETS was on the move again, to Kwajalein in the north Pacific but, as had been the case on Tawara, the flight nurses had to wait until adequate quarters were available before they could fly into that island. During the interim, the flight nurses of both the 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS participated in a week-long bivouac at Hickam Field.

The June 1944 squadron history notes that up until that month the 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS operated jointly evacuating casualties from the Gilbert and Marshall Islands to Oahu, but on 6 June the 809 MAETS was attached to the Pacific Wing of ATC. Under ATC control, “the 809th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron distributed personnel over the inter–theater run of the Air Transport Command in the Pacific, evacuating patients from the South, Southwest and Central Pacific to the mainland”. 4 Flight A was sent on Detached Service to Guadalcanal; Flight D was sent on Detached Service to Townsville, Australia; Flight C was sent to Kwajalein to work with the 812 MAETS evacuating patients back to Oahu; and Flight B remained at Hickam Field to evacuate patients from Oahu to the US. 5

By July, Flight C of the 809 MAETS was evacuating casualties from the Battle of Saipan back to Oahu via Kwajalein, while the other Flights continued attending patients on flights from the Southwest Pacific area back to the US. In August Flight D moved from Townsville to Nadzab, New Guinea, and Flight C returned to Hickam Field to augment the personnel evacuating patients to the US. The 2 squadrons noted a substantial increase in patients evacuated that month. The 828 MAES arrived at Hickam Field in August and worked in conjunction with the 2 squadrons already stationed there. The squadron history notes, “The necessity for having personnel located in so many widely separated stations required the services of at least one additional squadron, in order to properly carry out the mission of medical air evacuation in the Pacific Ocean Area.” 6

The flight nurses of the 812 MAETS graduated from their training course at the School of Air Evacuation on 2 October 1943; their squadron was alerted for overseas movement that same month. Intensive squadron training followed, and the squadron departed Bowman Field by train in early December. They took advantage of an hour layover in Kansas City for close order drill on the station platform for about 45 minutes; the nurses were led by chief nurse Elizabeth Pukas. “After the exercise all boarded the train in much better humor due to the exercise,” the squadron history reports. 7 Unlike their sister 809 MAETS, the 812 MAETS personnel arrived at Camp Stoneman, CA for staging.

Staging was in some ways a continuation of the preparations the 812 MAETS had made before leaving Bowman Field. Under the command of the San Francisco Port of Embarkation, Camp Stoneman had opened in 1942 to stage troops departing by ship for the Pacific Theater of Operations. Camp Kilmer in New Jersey served a similar purpose, staging troops that were transported to the European Theater of Operations. In these camps the troops’ military clothing and equipment were checked and replaced as needed; new impregnated clothing and gas masks were issued, and troops were sent through the gas chamber. They practiced boarding and disembarking the ship using the landing nets, and use of life rafts and life boats was explained. Administrative work was brought up to date. 8

On 16 December the 812 MAETS boarded the USS Monticello and sailed across the Pacific, arriving at Hickam Field on 21 December. The squadron’s personnel immediately began working in conjunction with the 809 MAETS. A flight nurse in the 812 MAETS, who wished to remain anonymous when interviewed, remembered her impatience between graduation and shipment overseas – she even contemplated quitting the military so that she could do some nursing again – and how disappointed the flight nurses in her squadron were when they arrived in Hawaii

and things weren’t organized for us to fly yet. The 809th were flying, but there weren’t enough flights yet at that time, and I don’t know whether they had enough airplanes or not. … we were at loose ends quite a bit of the time, and then they sent us out on bivouac. And mostly, we were a little discouraged that we weren’t doing something faster. And I can’t remember exactly how soon we started flying in earnest, but it took at least 3 or 4 months to get started. 9

The squadron history for January 1944 reports, however, that the first 4 nurses were assigned on Detached Service to Canton for air evacuation activities. 10

When in May 1944 the flight nurses of the 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS were restricted from flying into Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, resulting in down time, they were taken on bivouac in the Hawaiian mountains for an expected 2 weeks. Flight nurses served in key positions such as executive officer, mess officer, plans and training officer, and supply officer under the direction of their squadron commander. 11

From reports in the squadron history, the event had enough perks to make it more tolerable than the bivouacs experienced at Bowman Field. The flight nurses only had to walk the last 2 miles to their bivouac site, having had truck transportation the first 10 miles. Enlisted men had set up the tents and sanitary facilities and cleaned the area. Perhaps it was the heavy rain, the number of lectures on medical subjects such as tropical diseases followed by quizzes, the inspections, or the calisthenics, athletics, and 3–hour hikes that put a damper on the flight nurses’ spirits. But meals offered fresh fruit, vegetables, and meat, transportation was provided for the nurses to attend church services, and evening entertainment around a campfire included movies, a wiener roast, Coca–Cola, and beer. 12

Not the standard bivouac protocol, but not all the flight nurses were willing participants. In her report as Executive Officer, flight nurse Mary Reardon of the 812 MAETS wrote:

The attitude of the nurses toward the bivouac was questionable. There was a great deal of misunderstanding as to the reason for the bivouac and just where the plans originated. This was a topic for a great deal of discussion. Many of the nurses believed that they were not learning anything on the bivouac, and that the physical activity could have been carried on at the base under more favorable conditions. It must be said, however, that many nurses cooperated and tried to do their best to help in conducting the bivouac. 13

Recollections differed on the bivouac. Flight nurse Sally Jones Sharp of the 812 MAETS remembered years later that the bivouac was intended to last 2 weeks but “they brought us back after a week, because we made such a big fuss about it”. 14 Flight nurse quarters were available on Kwajalein the next month.

Like other flight nurses in the Pacific – the 801 MAETS, the 804 MAETS, and sister squadron 809 MAETS – the nurses of the 812 MAETS were limited in where they could be stationed due to inadequate quarters. For instance, in February 1944, permission was granted finally to station nurses at Tarawa, but air evacuation stations at Kwajalein and Eniwetok were manned by enlisted men, not by flight nurses. For this reason, their home base remained at Hickam Field throughout the war, even when squadron activities shifted to Saipan in mid–September 1944. Flight nurses interviewed years later remembered Canton, Tarawa, Kwajalein, Saipan, and Guam.

In November the 812 MAETS personnel were rotated between the various routes, with 2 Flights on the Saipan–to–Oahu run, 1 Flight on the Guadalcanal–to Oahu run, and 1 Flight on the Oahu–to–Hamilton Field, CA run. That same month a flight nurse and enlisted technician flew to Leyte in the Philippines on the first air evacuation mission to enter that island, returning with 24 Saipan casualties. Regular air evacuation flights into Leyte followed. 15

Chief Nurse Elizabeth Pukas elaborated on the issue of flight nurse quarters on the various islands:

I was always the first flight nurse to go into the zone, because while the material – strategic materiel – was emptied from the airplane, I was doing the liaison work of talking to the Navy who were in charge of the island for quarters for my nurses, making arrangements for bathing, for laundering, for feeding … Just the basic needs and nothing else. And quarters were tents on the mud or sand, whatever the island is.

When the war had developed, and then we changed headquarters from Hickam to Saipan to Guam, remember, this was a long time – many years. So when we went to Saipan, we changed headquarters, so to speak. We still had housing at Hickam, but they were very much smaller than we had had. 16

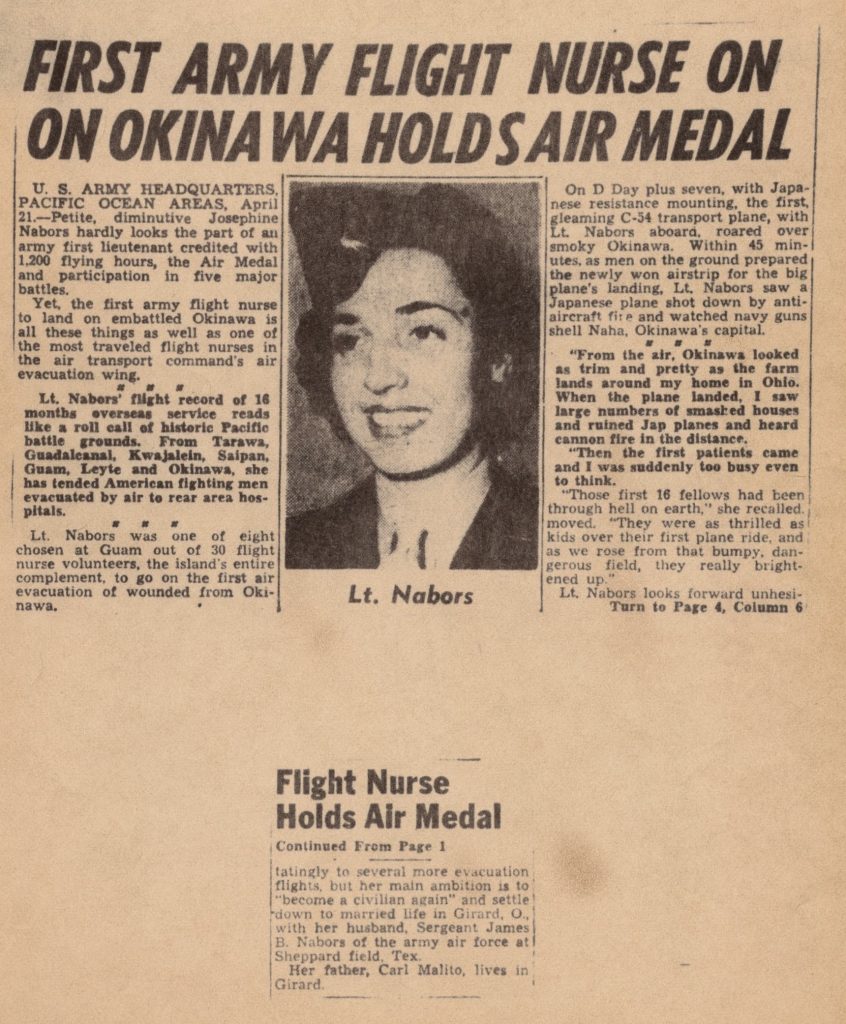

In another first, during the Battle of Okinawa, April through June 1945, Jo Nabors was the first flight nurse from the 812 MAES to fly into Okinawa, never thinking that hers would be the first of 8 names selected from a hat. She flew in on the fourth day after the bombing had begun, to pick up a load of patients, and was petrified, because she could see the devastation from the bombing and hear the firing. The patients were loaded and the flight was on its way 24 minutes later. 17

Honolulu newspaper clipping (AFHRA)

The presence of the 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS marked the beginning of organized air evacuation from the Pacific to the US. 18 But before those flights became massive in scale, focus intensified on the build–up to D Day in Europe as part of the Europe First policy.

For more about the 809 MAES and the 812 MAES, see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II. For more about flight nurses in the 812 MAES, see Blogs posted for:

Anonymous 22 Nov 2015 and 4 Apr 2020

Jo Nabors 20 Dec 2015 and 26 Apr 2020

Elizabeth Pukas 20 Sep 2015 and 2 Feb 2020

Sally Sharp 2 Apr 2016 and 1 Aug 2020

Audio recordings of my interviews with 3 of these flight nurses are available at

Jo Nabors https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011354

Elizabeth Pukas https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011355

Sarah Joan Sharp https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011358

Notes

- Mae M. Link and Hubert A. Coleman, Medical Support of the Army Air Forces in World War II (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1955), 400.

- “Squadron History Month of December 1943”, 809 MAETS, 2. [AFHRA MED–809–HI]

- “Squadron History Month of January 1944”, 809 MAETS.

- Squadron History Month of June 1944”, 809 MAETS, 1.

- Ibid., 1-2.

- “Squadron History Month of September 1944”, 809 MAES.

- “Squadron History Month of December 1944”, 812 MAES, 1. [AFHRA MED–812–HI]

- Ibid., 2.

- Anonymous, interview with author, 30 Apr 1986.

- “Squadron History Month of January 1944”, 812 MAETS.

- “Squadron History Month of May 1944”, 812 MAETS.

- Mary F. Reardon, “Report of Activities at Air Evacuation Bivouac Held 15 May 1944 to 22 May 1944”, 809 MAETS and 812 MAETS, 30 May 1944. [AFHRA MED–812–HI]

- Ibid.

- Sally Jones Sharp, interview with author, 21 May 1986.

- “Squadron History Month of November 1944”, 812 MAES.

- Elizabeth Pukas, interview with author, 9 Apr 1986.

- Jo Nabors, interview with author, 1 May 1986.

- Link and Coleman, Medical Support, 400.