The Twenty–third in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

MAETS and the Focus on Europe

Part 2

816 MAETS Activated November 1943

The 813 MAETS, which in 1944 considered itself one of the best in the European Theater of Operations (ETO), might have met its match in the 816 MAETS that arrived in the ETO in April 1944. Louise Anthony de Flon of the 816 MAETS had heard from chief nurse June Foster that her squadron was always rated by Command as one of the “highest … And she told me that whatever they asked us to do was done the best. There was never any laxness. There was never anyone who shirked their duty. And it may sound a little bit boasting, but actually we felt that if there was anything good, we got it.” 1 The squadron indeed had 2 firsts about which it could boast.

Following their arrival at Station #486 Greenham Common, flight nurses spent their first few months in the ETO engaged in the same activities as their colleagues in other squadrons – helping out in dispensaries, working in sick quarters, participating in air evacuation missions from England to Scotland, and traveling on Temporary Duty to bomber bases to get firsthand experience in dealing with casualties of war. Although the flight nurses found this last experience profitable, the 816 MAETS flight surgeons were less certain. “The observing of B–24s taking off and landing may have been exciting, the briefing and interrogations must have been interesting, but should it have taken two weeks to see all of this?” the unit historian wrote – a week would have been long enough. 2 But when D Day finally arrived, the 816 MAETS was the first to fly into Normandy to evacuate patients, on 10 June, “beating” the 806 MAETS, whose first authorized flight was on 11 June, by a day. 3 The Flight that had been sent on Detached Service to Membury the previous month flew the mission, which returned the patients to that base. The 816 MAETS historian details the preparation for the trip; military historian Robert Futrell’s account of the mission to Normandy under heavy fighter cover that “someone in higher headquarters” ordered, with news correspondents aboard photographing the flight nurses picking poppies while the C–47s sat on the ground for more than 2 hours before 15 casualties were “rounded up”, suggests more photo op than serious medical air evacuation. 4

The photo op tarnished the flight nurse image, chief nurse June Sanders of the 819 MAETS, whose flight nurses were awaiting their own opportunity to evacuate the wounded from France, complained. “We knew that our battle for Air Evac had slipped a trifle. – That we had left ourselves open for the ridicule of our ground force sisters – that we would henceforth be referred to in this theater as ‘The Poppy Girls.’ We have been.” 5 The Associated Press article “Nurses Pick Poppies While Awaiting First Wounded”, which appeared in a New Jersey newspaper, reinforced the “Poppy Girls” image. Suella Bernard and Marijean Brown, who had been among the flight nurses photographed holding bouquets of poppies in the doorway of their C–47 in France, wrote of their experience on the flight, beginning: “We picked poppies in shell–pocked fields of Normandy and brought them back to Britain with the first cargo of wounded to be evacuated from this new European battlefield – two Germans, a French civilian, and two Americans – a Colonel and a G.I.” 6

816 MAETS chief nurse June Foster (right) greets Suella Bernard

(left) and Marijean Brown (center) after their first air evacuation

flight into Normandy after D Day (USAF Photo)

The 816 MAETS made daily air evacuation missions to France for the rest of the month, and, with the Flight returned from Membury at month’s end, awaited movement orders. In July the squadron moved to Prestwick, Scotland where they began flying on ATC planes to evacuate patients back to the US. Given the heavy workload of the 816 MAETS, flight nurses and enlisted technicians from other MAETS in England were sent to Prestwick on Detached Service as needed. On 1 of those flights on 26 July 1944, Catherine Price, a flight nurse on Detached Service from the 817 MAES, an enlisted technician from the 816 MAES, and the 18 patients onboard were declared Missing in Action and presumably killed when their plane disappeared off the southern coast of Greenland. A month later Vivian Cronin, a flight nurse on Detached Service from the 818 MAETS, and a flight surgeon from the 816 MAES were was killed returning from the US when their plane struck a radio tower at night in bad weather, crashed, and burned in Prestwick.

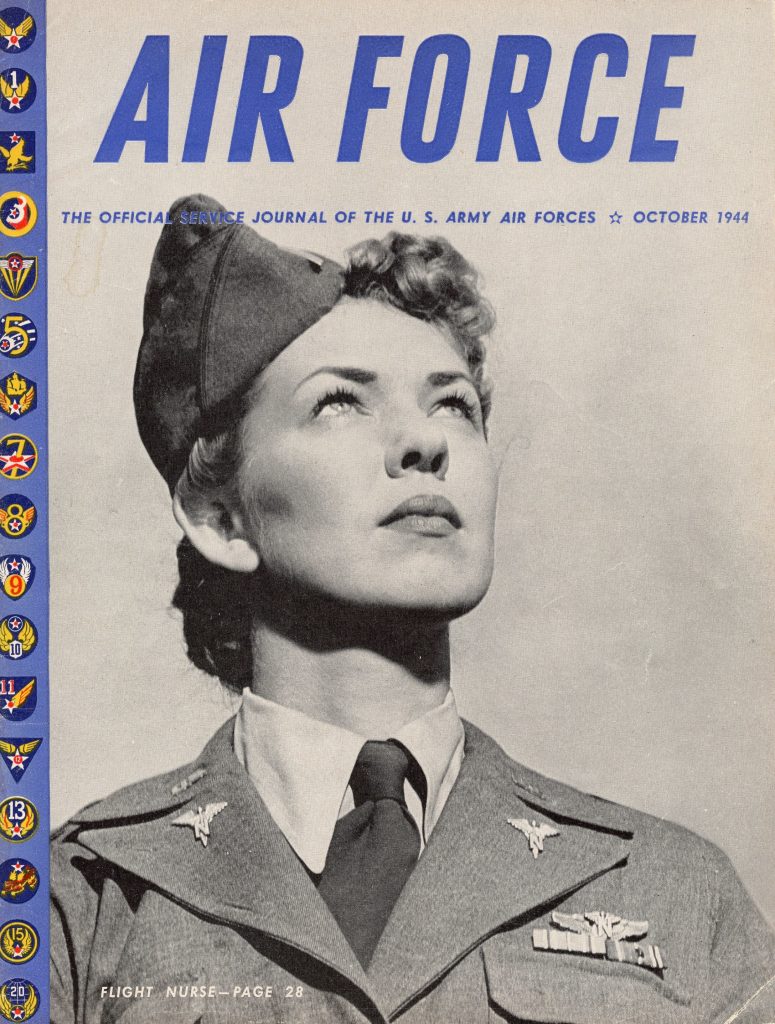

Finally in October 1944 the 816 MAES left Prestwick for Strip A–35 Le Mans, France, where it was joined by the 817 MAES a few days later to evacuate patients from France. That same month 816 MAES flight nurse Frances Sandstrom was featured on the cover of Air Force magazine after arriving in New York from a transatlantic mission. Sandstrom Crabtree explained how it came about in an interview years later:

Well, they were looking for someone for the Air Force magazine, and this lady – I’ll never forget, I’ll bet she thought I was crazy – she said, “Oh, are you a WAC?” “Oh, no.” “What are you?” “I’m a flight nurse.” “Oh, just sit right there. Don’t leave.” And I said, “Don’t worry, lady, I can’t even get out of this chair.” I was waiting for someplace to put my little head after flying all the way across from England. Oh, gosh, that was funny. 7

The photo shoot took place the next morning after Sandstrom had had a chance to freshen up.

816 MAES Frances Sandstrom (Author’s Collection)

The 816 MAES remained in France through the end of the year, moving from Le Mans to A–50 Orleans in November. From this station they sent flight nurses and enlisted technicians to Istres, France to evacuate patients from the Belfort Gap area with 811 MAES and 815 MAES personnel. December was remembered for often hazardous air evacuation missions from forward airstrips in France and Belgium back to Paris and the United Kingdom. But none of the air evacuation personnel ever tried to get out of these “difficult nerve–wrecking months” or complained of too much flying, the unit historian noted. 8 Some flight nurse / enlisted technician teams were placed on Detached Service to Welford Park with the 815 MAES to assist in evacuation flights across the Channel from France to England.

By January 1945 air evacuation missions had decreased because of a lull in fighting, and hospitals in the United Kingdom were filled to capacity after the German break–through in the Battle of the Bulge. In March 1945 the 816 MAES moved from Orleans to A–42 Villacoublay near Paris, where air evacuation teams had been on Detached Service with the 818 MAES. That month marked the second “first’ for the 816 MAES.

In March 1945 flight surgeon and squadron commander and flight surgeon Major Albert Haug asked Bernard if she would go on an experimental glider mission to evacuate patients from across the Rhine. In a 1984 letter to her friend Louise Anthony de Flon from the 816 MAES, Bernard Delp recalled the situation as one of traffic congestion to and from the Front after the Allies took Cologne, since they had only the one little bridge at Remegen that the Germans had failed to destroy. “At any rate, I said, ‘sure’ I would do it and I really had no fear about it. – It was going to be a short flight (a matter of minutes) and similar to what we already did in Air Evac, as far as the wounded were concerned.” The flight occurred on 22 March. Bernard continued:

I do remember that we had to wait quite a long time for the wounded to be brought out to the glider; I remember that, at the precise moment the C–47 tow ship lifted the glider off the ground, one of the ropes holding up one row of wounded (3 pts.) broke and the T/Sgt and another man (observer, I think) had to struggle to help secure it again; I remember being terribly concerned about the pts., one of whom was unconscious with his head completely bandaged; (actually, upon landing, the pts. were all safe and intact – that is, just as when we left on the flight) I remember that one of the wheels on the glider collapsed when we landed in the field and we ended up near a fence; I remember that we had a fairly smooth landing anyway (a very good pilot, I’d say). 9

Suella Bernard tending to patients in glider before C–47 arrived, March 1945 (USAF Photo)

Each of 2 gliders – one with the flight surgeon, the other with the flight nurse – transported 12 seriously wounded patients safely across the Rhine to the main air evacuation field at Euskirchen on the west side. The next month, the 816 MAES was transporting patients across the Rhine in engine–powered flights, and their air evacuation total in April was the highest for any month since the squadron began evacuation. 10

The 816 MAES remained at Villacoublay until the end of May, when their air evacuation commitments ceased. Up until that time the squadron had evacuated just over 7,000 patients from forward strips in Germany to England and Paris. The flight nurses flew on transatlantic missions from Orly Field as well until mid month when the squadron was alerted for redeployment to the Pacific Theater. Transfer of personnel into and out of other MAES followed – some to the 806 MAES, which was to remain in Europe with the Army of Occupation. June 1945 marked the end of air evacuation activities for the 816 MAES in the ETO. The officers of the 816 MAES in Europe credited the non-flying personnel for their squadron’s successes, and the unit historian offered an apt football analogy. These men were like linesmen, he said, without whose fundamental and vitally important role the “spectacular” flying personnel backfield would be unable to accomplish their missions. 11 The squadron had begun at Bowman Field, KY and ended at Villacoublay.

From the time that we began to evacuate patients, on June 10th D+4, from Omaha Beach until the last evacuation mission to Air Strip R4 Gotha, Germany, our nurses and surgical technicians have never failed to give their best on every flight, whether in the more o[r] less routine evac mission from areas far from the enemy lines or the more dangerous and exciting missions in which patients were picked up from air strips within hearing or visual distance of enemy batteries, and in the privilege of air evacuation of our wounded from Scotland and Paris to the United States. 12

For more about flight nurses in the 816 MAES through the 819 MAES see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II. For more about flight nurses in the 816 MAES, see Blogs posted for:

Frances Sandstrom Crabtree 18 Dec 2016 and 10 Apr 2021

Louise Anthony de Flon 6 Jun 2016 and 10 Oct 2020

Jenevieve (Jenny) Boyle Silk 30 Jan 2016 and 14 Nov 2020

Brooxie Mowrey Unick 14 Aug 2016 and 6 Dec 2020

Audio recordings of my interviews with some of these flight nurses are available at:

Frances Crabtree https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011344

Louise DeFlon https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011348

Jenny Silk https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011357

Brooxie Unick https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011368

Notes

- Vivian C. Cipriano, 813th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Unit Historical Report 1 December 1944 – 31 December 1944”. [AFHRA MED–813–HI]; Louise Anthony de Flon, interview with author, 23, 24 May 1986.

- “816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Historical Report June 1945”, 28–29. [AFHRA MED–816–HI]

- “History 806th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron”, [Jun 1944] [AFHRA MED–806–HI]; “816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Unit History for Month of June 1944”, 3.

- Initial Installment of Unit History for 816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron”, 33–34; Robert F. Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation in the USAF, 1909–1960, Historical Studies No. 23 (Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University; Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs / Aerospace Historian, 1960), 209.

- June Sanders, “Unit History for Month of June 1944”, 819 MAETS, 3. [AFHRA MED–819–HI]

- Suella Bernard and Marijean Brown, “Nurses Pick Poppies While Awaiting First Wounded”, Newark CALL, 12 Jun 1944.

- Charlotte Knight, “Flight Nurse”, Air Force 27 (10) (Oct 1944), cover, 61; Frances Sandstrom Crabtree, interview with author, 21 Jun 1986.

- “816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Historical Report June 1945”, 75.

- Suella Bernard Delp to Louise Anthony de Flon, 10 / 2 / 84, private unpublished correspondence.

- “816th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron Unit History for Month of April 1945”, 1 May 1945, 2.

- “816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Historical Report June 1945”, 99.

- Ibid.