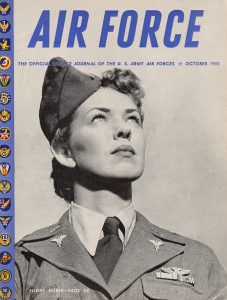

The First in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

The Quasi-Military Aerial Nurse Corps of America

Lauretta M. Schimmoler, a pilot from Ohio who in the 1930s founded the Aerial Nurse Corps of America (ANCOA), never intended the organization’s members to limit their work to civilian aviation activities. In Schimmoler’s mind, the military soon would need the services of trained flight nurses, and she would be ready with an initial cadre of women prepared for flight nurse duty. To that end she structured ANCOA along military lines.

Lauretta Schimmoler, circa 1932

Lauretta Schimmoler, circa 1932

(Bucyrus, OH Historical Society)

ANCOA was organized according to military command structure, with national headquarters in Burbank, CA, and 3 wings subdivided into 9 divisions throughout the US, each division corresponding to corps area boundaries found in the US Army. The divisions were subdivided into companies. But the military analogy went even further. ANCOA members were assigned honorary rank commensurate with their position: the national commander held the rank of colonel, a lieutenant colonel commanded a wing, a major commanded a division, and a captain commanded a company. Most of the nurses held the rank of first or second lieutenant, or cadet, which was the lowest grade for a registered nurse. 1 Like their military counterparts, those ANCOA nurses who met the qualifications took an oath of office “to support and defend the Constitution of the United States of America and the Aerial Nurse Corps of America against all their enemies whomsoever” and “to bear true faith and allegiance to the same”. 2 Should a member put too much stock in her quasi–military status, she need only remember the organization’s Ten Commandments that stressed such character traits as honor, loyalty, promptness, dependability, respect, integrity, and remaining true to one’s religion to restore her sense of perspective. 3

Because Schimmoler planned to work in conjunction with the American Red Cross (ARC), ANCOA nurses were required to be a member of their state nurses association and of the First Reserve of the ARC, which provided the pool of applicants from which military nurses were drawn.

ANCOA nurses served on “active duty” for 3 years during which time they agreed to perform nursing duties in any airworthy aircraft. Unlike military nursing, however, work as an ANCOA nurse was not full time but rather was limited to part–time volunteer participation in evening classes and weekend activities that included providing first aid for national air races and smaller air events. Occasionally ANCOA nurses would accompany a patient on a flight to provide nursing care en route. Members held other jobs as nurses and paid for the privilege of being part of ANCOA with a $5 enrollment fee and monthly dues of 50 cents. 4 They were required to attend 2–hour classes and lectures 1 night each week divided into medical subjects the first year, aeronautical subjects the second year, and theoretical subjects the third year.

All members had to pass an examination of the ANCOA Regulations Manual within the first 6 months of membership, after which the new nurses were placed on the active–duty roster, promoted from cadet to second lieutenant, and were authorized to wear the blue–grey ANCOA uniform with its overseas cap and military–like insignia. 5

Lauretta Schimmoler (far left) and original ANCOA

Lauretta Schimmoler (far left) and original ANCOA

members, National Air Races, Los Angeles,

1936 (USAF Photo)

World War II broke out before Schimmoler could “sell” ANCOA to the military, which by then had formulated its own plan for a flight nurse program that employed Army nurses as members of the 31 Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadrons (MAETS) – renamed Medical Air Evacuation Squadrons (MAES) on 19 July 1944 – activated during the war. 6 But many ANCOA nurses traded their quasi–military status for that of an officer in the US Army, some of whom served with distinction as flight nurses.

For more about ANCOA, see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in Word War II, Chapter 1. For more about Lauretta Schimmoler and ANCOA, see Blogs posted in 8 parts, beginning 1 Oct 2018.

Notes

- Aerial Nurse Corps of America, Regulations Manual (Los Angeles, Burbank, CA: Schimmoler, 1940).

- “Aerial Nurse Corps”, brochure, n.d., 4.

- “Ten Commandments of an Aerial Nurse”, Aerial Nurse Corps of America Memorandum, 20 Jun 1938.

- “Aerial Nurse Corps”, brochure, n.d., 4.

- Aerial Nurse Corps, Regulations Manual, 2–4; Leora B. Stroup, “A New Service in an Old Cause”, Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 105 (Sep 1940): 187–88.

- A revised Table of Organization 8–447 issued on 19 July 1944 re–designated the Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron as the Medical Air Evacuation Squadron. I use the MAETS acronym when writing about squadron activities occurring up to 19 July 1944, after which I use the MAES acronym.