A series of five Blogs discussing the literary component of

the story of Judith found in the Apocrypha in light of composer

Alexander Serov’s own professed expectations for opera,

to determine what may be considered quintessentially

Russian about his first opera, Judith.

A Russian Judith? Literary Reflections on

Alexander Nikolayevich Serov’s First Opera

Part 1

The Premiere

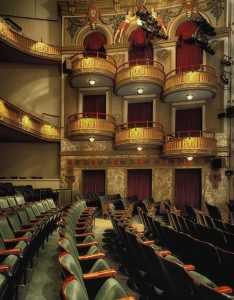

When Judith premiered at Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre on 28 May 1863, the production was hailed as an immediate success. Composed by Russia’s foremost music critic, the opera thrust Alexander Nikolayevich Serov (1820–1871) into the limelight as Russia’s foremost composer, at least of the moment. Music critic Vladimir Stasov, who, prior to engaging in journalistic polemics with Serov, had encouraged his first attempts at operatic composition, praised the premiere performance. “From the very first note Serov became the idol of Petersburg,” wrote Stasov to Russian composer Mily Balakirev. “You can have no conception of what happened yesterday. Everyone is crazy, everyone is enraptured as never before, they all say nothing like this has ever happened to us before, that he is our first composer since the creation of the world.” 1

According to some critics, Judith surpassed Mikhail Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842) as Russia’s best opera, placing the two composers in contention for top honors. 2 But within Serov’s own circle of colleagues, the reception of Judith was far less laudatory. Among members of the Mighty Handful, Russian composers who, in addition to Balakirev, included Alexander Borodin, César Cui, Modest Mussorgsky, and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Serov was viewed as a second-rate talent.

Dubbed “the Russian Meyerbeer” by Stasov for alleged triviality, shallowness, and concern with superficial stage effects in his second opera Rogenda (1865), Serov endured vitriolic attacks that challenged his status as Russia’s preeminent composer. 3 The very Russianness of his work was and continues to be questioned. That Serov had championed the introduction of Richard Wagner’s music into Russia was not overlooked by those critics and musicians who heard at least superficial characteristics of Wagner in Serov’s music. Other writers have attributed the influences of Gasparo Spontini, Giuseppi Verdi, Felix Mendelssohn, Charles Gounod, and even George Frideric Handel on Serov’s operatic music. Serov himself confessed his musical indebtedness to Ludwig von Beethoven, Carl Maria von Weber, and Felix Mendelssohn. He had highest regards for Giacomo Meyerbeer, Frédéric Chopin, and, above all, Wagner, whom he worshiped. 4

Given the accolades accorded to Serov following the premiere of Judith, the allegedly cosmopolitan nature of his music leads one to question what aspects of Serov’s first opera may be considered truly Russian. As was the case with his idol Wagner, Serov had strong views on the division and ordering of operatic components. Allowing for shifts in the relative importance of the three elements identified in an 1856 exposition as practical, musical, and scenic or theatrical, Serov nonetheless placed greatest emphasis on the first element, the content and idea of the opera as a play. 5

Continued in Part 2 The Book of Judith

To learn about the nurse character in Serov’s Judith, see Judith Barger, The Nurse in History and Opera: From Servant to Sister (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, May 2024).

Notes

- Perepiska, 1: 199–200; cited in Robert C. Ridenour, Nationalism, Modernism, and Personal Rivalry in Nineteenth-Century Russian Music, Russian Music Studies No. 1 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981), 122.

- Gozenpud, Russi opernyi teatr, 2: 62; cited in Ridenour, 122.

- Izbrannye sochineniia, 1: 150–51; cited in Ridenour, 124.

- Rosa H. Newmarch, The Russian Opera (NY: Dutton, 1914), 160.

- Serov, Izbrannye stat’i I, 255 cited in Richard Taruskin, Opera and Drama as Preached and Practiced in the 1860s, Russian Music Studies No. 2 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981), 49–50.