Oh How They Loved to Sing!

Although not a music journal, The Girl’s Own Paper (TGOP), published in London by the Religious Tract Society beginning on 3 January 1880, clearly considered music a worthy topic, which readers encountered in music scores, fiction, nonfiction, poetry, illustrations and replies to musical correspondents. Music in The Girl’s Own Paper: An Annotated Catalogue, 1880 – 1910, lists the many musical references found in the magazine.

One of the most frequently asked questions about music found in the Answers to Correspondents column apparently was the age at which a girl could begin voice lessons. During the magazine’s first year, correspondents Tot and Tiny were told, ‘The earliest age at which it would be safe for a girl to commence singing lessons is from fifteen to sixteen. You may sing if you like to amuse yourself, but that is quite a different thing from being trained.’ [Volume 1, p. 208] * Rachel was ‘certainly too young to learn “solo singing” at age thirteen’ and was told, ‘Wait till sixteen, or you will ruin your voice. Sing for amusement if you like – not as a lesson, with suitable training.’ [Volume 1, p. 352] At fourteen, Genevra also was too young – ‘sixteen is the earliest age for making a beginning’. [Volume 1, p. 623]

Beginning with the first article about singing found in TGOP, ‘Home Accomplishments I. How to Sing a Song’ by Madame Mudie-Bolingbroke, an Associate of the Royal Academy of Music, readers with ‘a pleasing voice and correct ear’ were encouraged to cultivate their voices. [Volume 1, p. 54] The wisdom of Robert Schumann, included in a Varieties column, reinforced this message:

SINGING.Try to sing at sight, without the help of an instrument, even if you have but little voice; your ear will thereby gain in fineness. But, if you possess a powerful voice, do not lose a moment, but cultivate it immediately, and look upon it as one of the best gifts Heaven has bestowed upon you. Schumann. [Volume 1, p. 143]

In a follow-on article, ‘How to Improve the Voice’, the popular soprano soloist Miss Mary Davies stressed management of the breath, with the aid of a good master and a good instruction book, and choosing exercises within the compass of the voice, not too high, not too low. In closing Davies identified the three necessary qualities of patience, perseverance and enthusiasm for anyone wishing to learn to sing. [Volume 1]

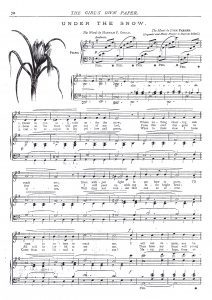

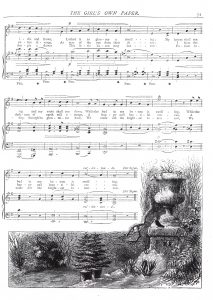

TGOP offered vocal sheet music in most of its weekly issues. The first, ‘Under the Snow’, is a two-page vocal solo with piano accompaniment composed by John Farmer, organist and Music Master to Harrow School, to words by nineteenth-century American poet Hannah F. Gould. The text encourages patience, like the crocus under the snow, in today’s gloomiest hour, for tomorrow will be brighter. [Volume 1, pp. 70–71] The piece gives an idea of the level of musical proficiency readers were expected to possess. Moving between minor and major modes, the piece with its 3/4 time signature has a simple waltz accompaniment that ends in the major mode. The even simpler vocal line beginning on the D above middle C peaks on F sharp a tenth above.

‘Under the Snow’, composed by John Farmer to text by Hannah Gould. The Girl’s Own Paper, Volume 1, pp. 70 – 71. [Lutterworth Press]

Amateur singing came with its own rules of etiquette. A vocalist should never refuse to sing if asked during a musical entertainment in someone’s home. As the editor told correspondent Alta in Volume 1:

It is wrong to persistently refuse to sing if you have a voice. Nothing is so thoroughly wretched to a stranger as to meet a girl at a musical party who refuses to exert herself to take part in the entertainment. It is conceited to be nervous. Nobody wants to hear you. It is the music of the composer and the words of the song that they wish you to expound to them. Try to do this intelligently, and all your mind will be so occupied that you will forget yourself. [p. 623]

Correspondent Zena Rosckma was told in the same volume that the hostess or daughter of the house always should sing first before asking her guests to do so. [Volume 1] And listeners should not interrupt the singing with conversation – an expected courtesy reinforced in the magazine’s nonfiction and fiction.

The care of the voice was an ongoing concern to correspondents apparently requesting remedies to improve their throats for singing. The advice given to correspondent Ruby, who ‘is going to sing for the first time publicly, and wants to have a clear voice’, is representative of those remedies:

Let her take a tonic for a fortnight before: ten drops of tincture of iron, and a teaspoonful of tincture of oranges three times a day in a little water for a fortnight or three weeks previous to appearing, and suck about five grains or more of solid chorate of potash an hour or two before singing. [Volume 1]

Vocal health was a concern as well to the magazine’s contributing physician ‘Medicus’, who offers relevant advice in ‘The Care of the Voice’ in Volume 1. Admitting that he has nothing to do with voice training, but only with the singer’s health, ‘which ought to be kept up to par with learning to sing or taking lessons’, the author gives sensible advice: do not strain the voice or try to sing too high or too low, and do not sacrifice sweetness and expression for loudness of tone. ‘I love a song with a soul behind it’, the straight-talking physician says, ‘but when I’m compelled to listen to one who screams I wonder to myself what wrong I’ve committed to deserve so great an infliction. Well, then exercise of the voice ought always to be in moderation.’ [Volume 1, p. 454]

TGOP fiction contrasted proper with improper use of the voice from a moral as well as vocal standpoint, beginning with the 40-chapter serialized fiction ‘Zara; or, My Granddaughter’s Money’ that opened the magazine’s first issue. When Paul Tench finds Zara Meldicot Keith to give her the money left by her now deceased grandmother at his family’s lodging house long ago, Zara is a milliner’s assistant by day and a music-hall singer by night. In an effort to dissuade her from a singing career, Paul asks Zara whether she has ever considered ‘what immense application, what careful study, what years of education, of practice, of travel, it requires to make a really brilliant “artist”’. She replies naively, ‘I should think a good voice with very little teaching would do.’ [Volume 1, p. 210] Significantly, the fortune is handed over to Zara only after she has left the music hall and married a responsible man. Rose Everleigh’s story in Anne Beale’s ‘Quite a Lady’ contrasts with Zara’s. When her mother dies, Rose relies on her vocal talent for much needed income. She finds her one paid engagement as a concert singer so distasteful, though, that she vows to starve rather than reappear on stage. But Rose did not starve, for she, too, was ‘rescued’ financially by marriage. [Volume 1]

The stage was set, literally and figuratively, for messages that the magazine conveyed to its readers about the role of music in their lives. In ‘Higher Thoughts on Girls’ Occupations’ in Volume 4, Alice King’s voice was the first of many in TGOP’s ongoing crusade against the nuisance some would-be musicians were to others. Girls with musical aspirations fall into two categories – the bullfinches and the parrots – King wrote. The first group, who show evidence of talent at an early age, should be nourished in their musical studies. The second group should be encouraged to spend their time in other, nonmusical pursuits. Fiction reinforced the message. In ‘Three Years of a Girl’s Life’, serialized in 17 chapters in Volume 1, Clara Henderson’s singing voice is like a peacock’s pitched an octave too high; her sister Alice’s contralto is reminiscent of a bird with a cough.

Picking up on the tone of such fiction, the Varieties column treated vocalists to an abundance of lighthearted banter such as ‘How She Sang’ in Volume 18:

Edith: ‘You can’t imagine how Mr. Bullfinch appreciated your singing.’

Ethel: ‘Did he, though?’

Edith: ‘Yes; he said it was simply heavenly.’

Ethel: ‘Really?’

Edith: ‘Well, just the same thing; he said it was simply unearthly.’ [p. 710]

For the uncommonly talented, King considered music a legitimate calling when approached earnestly and soberly, ‘keeping firm hold of the Almighty hand’, and wearing ‘the whole armour of Christ’. [Volume 4, p. 823] A good voice was considered a gift from God to be used to glorify him. Fictional heroines who choose public singing careers often lose their grip or their armour and find themselves headed down a slippery slope to ruin until a life-changing event redirects their path. For 17-year-old Marietta Stefani in a small Tuscan village, the opportunity to study singing in Florence offers a means to reverse her struggling family’s financial setback. But despite warnings, Marietta lets her head be turned by her new life. Realising her folly, Marietta stops singing in public but shares her gift of song with family, friends and charities, and thanks God that she turned back from the perilous road on which she had started. [Volume 7]

In Eglanton Thorne’s ‘Her Own Way’, serialized in 28 chapters in Volume 16, Juliet Tracy wants to be a public singer, for its splendid life standing before an audience with every eye on her, ‘listening spell-bound to her voice’. [p.146] When permitted to take singing lessons from an Italian master, Juliet reads into his words only what she wants to hear rather than the truth, letting vanity fuel a dream that her vocal progress does not support. A number of mishaps highlighting the dangers of selfish actions and vocal study abroad leave Juliet penniless and thankful for the home to which she returns, where she puts her gift to good account, singing in her parish choir. ‘We cannot take our own way and God’s way, too,’ the author moralizes. [p. 227] Myles Foster had voiced a similar message in ‘Singing in Church’ in Volume 5: readers who pay for expensive singing lessons to master ballads during the week should give equal, careful and prayerful attention to singing church hymns in congregation and choir stalls on Sundays.

The magazine made a clear distinction between those girls who pursued music as a pastime and those who pursued it as a profession, and most heroines who took the latter route eventually left it for the more enduring fame of marriage and motherhood. Eighteen-year-old Odette Gerard, in ‘Odette: Soprano: A Story Taken from Real Life’, serialized in 42 chapters in Volume 27, travels to Florence to study voice on a meagre £50. When at the end of two years her money has run out and she learns it will take two more years of training to make a credible debut, the discouraged singer marries a British physician who has been hovering in the background and returns to England to take up ‘that other song, the song of love and home’. [p. 451] Odette’s story illustrates the premise of Madame Melba’s article ‘Why So Many Students Fail in the Musical Profession’ printed in Volume 30 of TGOP. The well-known vocalist offers practical advice concerning young women who flock to the Continent, lured by the glamour of a professional singing career, but who lack the true talent and adequate finances to sustain their vocal study.

And, lest readers forget that one should sing only for selfless purposes, the message often was reinforced in the magazine’s fiction. In Sarah Doudney’s ‘The Angel’s Gift’ in Volume 22, only John Rayne, one of a trio of young men with the ‘angel’s gift’ of song, uses his talent wisely when he becomes a cathedral chorister; the other two seek fame and fortune and eventually lose their voices. John’s sister Avice, who accompanies the singers on the organ, reminds them gently ‘that a divine gift should be used only for divine ends.’ [p. 146]

As Mudie-Bolingbroke wrote in Volume 1, the natural voice, unlike artificial instruments, has the power to appeal to the heart; the singer was encouraged to sing from her own heart to touch the hearts of her listeners. The author’s conclusion from Longfellow set the tone for the magazine’s continued approach to this popular accomplishment: ‘God sends His singers upon earth / With songs of sadness and of mirth, / That they may touch the hearts of men, / And bring them back to Heaven again.’ [p. 56]

* Complete citations may be found in Judith Barger, Music in The Girl’s Own Paper: An Annotated Catalogue, 1880 – 1910 (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).