Instruments and Instrumentalists

in The Girl’s Own Paper

Part Two: The Organ

Although not a music journal, The Girl’s Own Paper (TGOP), published in London by the Religious Tract Society beginning on 3 January 1880, clearly considered music a worthy topic, which readers encountered in music scores, fiction, nonfiction, poetry, illustrations and replies to musical correspondents. Music in The Girl’s Own Paper: An Annotated Catalogue, 1880 – 1910, lists the many musical references found in the magazine.

During TGOP’s first decade, ‘how to’ primers on playing musical instruments appeared, from singing a song in Volume 1 to playing the zither in Volume 10. Piano, violin, organ, harmonium, harp, guitar, concertina, mandolin, banjo and xylophone rounded out the list. Of all the primers, only those for singing, pianoforte and violin appeared more than once, suggesting that these were the preferred forms of music making to which TGOP readers should – and did – aspire. Unlike banjo playing, the focus of the previous blog, organ playing was encouraged because of its usefulness in houses of worship.

John Stainer, organist of Saint Paul’s Cathedral and organ professor at the National Training School for Music, set the tone for making music on that instrument when he told readers of TGOP in ‘How to Play the Organ’, simply to ‘do it’. [Volume 1, p. 328] * His technical approach to instruction may have been off-putting to some readers, however. After guiding them through the perils of reaching an organ in an imaginary church loft, he introduces them to ‘four rows of keys, one over the other, a row of foot-keys or pedals below them, sundry little iron levers, called composition pedals, and fifty stops, twenty-five on each side’. [pp. 328–29] He then explains the meaning behind the names and numbers on these stop-handles regarding compass, pitch and tone. Only after becoming acquainted with the stops and manuals is the imaginary organist permitted to take a seat on the bench and begin trying the organ.

Readers wanting a less complicated instrument to play may have been discouraged by King Hall’s ‘How to Play the Harmonium’, which followed in the same annual volume of the magazine. ‘I dare say you, my kind reader, will be able to recall without much difficulty the disappointment, and perhaps disgust, with which you have risen from the harmonium after attempting to perform some simple piece of music for the first time,’ the author writes. [Volume 1, p. 472] Hall admits that this reaction is normal, for the harmonium is not an easy instrument to learn and may initially seem refractory and arbitrary; even the organ, with its complicated construction, is more straightforward in its challenges, he contends. He then draws on organ construction to explain construction of the harmonium and its stops, pitches and tones. But the author ends with a reassuring ‘Do not be disheartened, dear reader, a little perseverance is all that is necessary to enable you to overcome the difficulties which perhaps at first appear almost insurmountable.’ [p. 473]

TGOP already had organists among its readers, some of whom played the harmonium, before Stainer’s and Hall’s primers appeared in the magazine. Poppy, A Village Organist and Mary all had inquired about the organ and received replies in the correspondence columns; replies to M.A.B., Marian and Sweet Seventeen followed in the magazine’s first year. [Volume 1]

Most correspondents apparently asked sensible questions to which the magazine’s editor responded in like manner. Correspondent Marigold, however, must have been an exception. The editor, who was known on occasion to have a bit of fun at the correspondent’s expense, wrote: ‘MARIGOLD wishes to know “if a boy of twenty can learn to play an American organ?” Why not? What is the matter with this somewhat “elderly” boy? Has he lost all his teeth, or his hair? What prevents his learning to perform on either the hurdy-gurdy or the French horn, unless the tips of his fingers were frost-bitten? Foolish Marigold, those chilblains of yours must have affected your head.’ [Volume 6, p. 655]

Correspondent Scotia’s request could not be granted. ‘We cannot give you lessons in playing the harmonium,’ the editor wrote; he referred her to Hall’s article in Volume 1. [Volume 8] Correspondents Judie, Norah and Birdie were referred to the London Organ School and International College of Music for lessons; A Quaver was given information about the Royal College of Organists. [Volumes 5, 15, 16, 22]

That TGOP expected to have organists among its readers is evident from the help the magazine offered them in choosing repertoire for the instrument. Beginning in Volume 9 through Volume 19, TGOP included what it considered suitable pieces for American organ or harmonium among its printed music scores, listed below.

Volume 9

Rêverie (J.W. Hinton) (harmonium or American organ)

Volume 12

Allegretto Giojoso (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

Andante Pastorale (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

Volume 13

Crusaders’ March (Myles B. Foster) (harmonium or American organ)

Elegy (Myles B. Foster) (harmonium or American organ)

Meditation (Myles B. Foster) (harmonium or American organ)

Volume 14

Supplication (Myles B. Foster) (harmonium or American organ)

Volume 17

Postlude (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

Volume 19

Adagio ma non Troppo (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

Allegro con Moto Agitato (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

Chorale (Myles B. Foster) (pianoforte or American organ)

The magazine’s Notices of New Music column, which appeared under slight title variations, included short reviews of organ music that its readers might try out; a young woman ‘At the Organ’, shown below, illustrates a Volume 9 column.

‘Notices of New Music’, The Girl’s Own Paper, Volume 9, page 177.

‘Notices of New Music’, The Girl’s Own Paper, Volume 9, page 177.

(Lutterworth Press)

Some of the magazine’s fictional heroines played the organ, beginning with May Goldworthy in Ann Beale’s ‘The Queen o’ the May’, serialized in 27 chapters in Volume 2. At age six, motherless Madeline (May) Goldworthy is sent from London to live with her great-grandparents in the coal-mining district of Wales. Musical from an early age, May later takes organ lessons, sings in a choral competition at the Crystal Palace and uses her musical talent to help support her family. In ‘May Goldworthy’, the four-chapter sequel to the story in Volume 3, the heroine, who has become a professional concert singer in London, returns to her Welsh village as new bride and wife of cousin Meredith and resumes her role among family and friends, which includes singing and playing harmonium for the benefit of others.

Correspondent Iresene’s gracious letter to the editor in Volume 2 likely inquiring about transferring her keyboard skills from harmonium to organ, introduced a misconception that was promulgated in music journals contemporary with TGOP – that organ playing could be injurious to a female player’s health. The editor warned: ‘We think that if you play the harmonium you would soon learn the organ stops; but the playing with the pedals requires a good deal of practice and is trying to the back. To many women it would be very injurious.’ [p. 160] Correspondents Cecil Burn and Mildred Daisy, Rob Roy and Lady Organist were given similar replies. The activity looked strenuous, but the magazine’s answer must not have satisfied its readers, who continued to ask the same question. In Volume 17 on a page of ‘Replies to Often-asked Questions’, the magazine’s answer to ‘Is Organ-playing bad for Girls?’ reflected a change for the better in its thinking on the matter: ‘Organ playing is not injurious to either sex, indeed it is a healthy though fatiguing occupation. It exercises the muscles of the hands and renders them delicate and precise. The movements of the legs in working the pedals are natural ones, being almost identical to those of walking.’ [p. 512]

TGOP worked organ playing into its articles on self-improvement. ‘Just Out’ printed in the magazine’s first year of publication encourages musical girls to practice piano diligently once they have left school, for some day they might ‘be required to play the organ in church, the harmonium at meetings, to accompany friends in part or solo singing, and at all times you will be able to give a great deal of pleasure to those around you who are fond of music’. [Volume 2, p. 775] J.P. Mears’ ‘How to Improve One’s Education’, which appeared about a year later, gives recommendations for practising on piano and on harmonium. [Volume 2]

In 1891, correspondent Annie Findburgh asked the editor of TGOP what was the ‘usual amount of salary for an organist’. She was told that salary, which could range from £20 upwards, was based not on the amount of work done, but rather on the wealth and generosity of a congregation or parish, and in answer to what must have been another question, was told, ‘We never heard of a home being supplied.’ The editor continued: ‘You have formed very grand ideas about the worth of such an appointment.’ [Volume 13, p. 16]

‘Pimpernel’, an organist from Plumstead, won third prize in ‘Our Competition for Professional Girls’ sponsored by TGOP in 1897. A graduate of the Royal Academy of Music, ‘Pimpernel’ trained as a singer but could not get enough engagements, so she teaches music and plays the organ for church instead. Her essay is found in Volume 18.

‘Pimpernel’ was paid for her services, but many of her sisters on the organ bench were not. In ‘The Amateur Church Organist’, The Hon. Victoria Grosvenor urges readers with musical talent and leisure to qualify themselves as amateur organists for churches in agricultural and suburban parishes unable to pay a professional organist. [Volume 8] Ruth Lamb’s fictional ‘Only a Girl-Wife’, serialized in 25 chapters in Volume 7, had remarked on this type of ministry. After-dinner music at the Crawford’s house contrasts two types of singers. Grace Steyne, the rector’s daughter, is far behind the ‘girl-wife’ hostess Ida in brilliancy and style but has a fine voice that she uses ‘with true musical taste’, not attempting anything beyond her ability. Grace’s music making is a labour of love – she plays the organ at church and trains the village choir, ‘not a very easy task when scarcely any of the members knew their notes so as to read the music’. [p. 366]

Correspondent Isa, who wrote to the editor in 1884, exemplified the selfless service that TGOP encouraged in its readers. He responded: ‘We thank you sincerely for the kind testimony you give to the spiritual usefulness of this paper, and your wishes for still further blessing on our work. May your own be prospered also – your acting as organist for your church as a free offering to God’s service, and your Sunday-school teaching.‘ [Volume 5, p. 240] Correspondent ‘Bride of Triermain’, a harmonium player, likely took on more than she could handle, judging from the editor’s reply to her letter in Volume 3: ‘We advise your consulting the rector on the subject of your inefficiency as his assistant in playing the harmonium. Tell him you are anxious to improve, and need some lessons; and let such a suggestion as that of your receiving them from his daughter emanate from him or her, not from you.’ [p. 286]

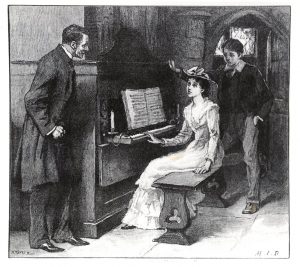

Fictional organists in TGOP served as role models for the magazine’s readers who were organists. Ivy Gardiner, in ‘The Organist’s Daughter’ in Volume 14, takes over her father’s organist duties when his health fails. Confident in the role, she also meets with the parents of his piano pupils to encourage continued lessons under her tutelage. In Ada M. Trotter’s ‘Marsh Marigolds’, serialized in 25 chapters in Volume 16, Ritchie Marphell, pictured below, takes over her father’s church organist duties when his vision fails. Only 16 years old, she has trouble maintaining order during rehearsals when cantankerous male choir members challenge her ability to direct them. Ritchie’s rector defends the young organist against the assaults of her enemies. ‘Oh, how good you are!” she tells him after a particularly trying evening. [p. 65] In Sarah Doudney’s ‘The Angel’s Gift’ in Volume 22, Avice Rayne, who accompanies on the organ a trio of young men with the ‘angel’s gift’ of song on the organ, reminds them gently ‘that a divine gift should be used only for divine ends’. [p. 146]

Ada M. Trotter, ‘Marsh Marigolds’, The Girl’s Own Paper, Volume 16, p. 65.

Ada M. Trotter, ‘Marsh Marigolds’, The Girl’s Own Paper, Volume 16, p. 65.

(Lutterworth Press)

In Eglanton Thorne’s ‘Midst Granite Hills: The Story of a Dartmoor Holiday’ in Volume 12, Grace Erith has given up her music governess position, to nurse her brother back to health following his time at university. An admirer offers a cottage in Dartmoor for his convalescence; in return, Grace serves as organist at the village church. Madeline Stuart in ‘Music Hath Charms’, by A. Mabel Culverwell in the same volume, has been taking lessons from the parish organist since age 13. She has to think about her livelihood, for the four Stuart siblings are orphans and must make their own ways in life. Providentially, the parish organist’s untimely arm injury puts Madeline on the organ bench as his substitute for the Christmas season, leading to a position as a music governess. [Volume 12]

Like Ivy, an organist’s daughter, Beatrice Vaughan in M.M. Pollard’s ‘The Organist’s Niece’ in the Snowdrifts extra Christmas number for Volume 6 takes over her uncle’s organist duties when he falls ill. In ‘Acquired Abroad’ by Louisa Emily Dobree in the same extra Christmas number, Ellice Creswell learns that honesty is the best policy. To qualify for a morning governess position to support her blind mother and herself, Ellice is tempted to claim that her French has been acquired abroad, when in fact she has only visited Paris. After seeking her mother’s counsel, Ellice declines the position, then takes solace on the organ bench of her village church. The rector, in need of an organist, hears Ellice playing and, after learning of her troubles, offers her the position.

For Nessie Cartwright and her friends in ‘Noël; or, Earned and Unearned’, a story in the Christmas Roses extra issue for Volume 3 by Grace Stebbing, the lesson is about charity. When a church offers an organist post to Nessie, who needs a paying job, her rich friend cannot understand why Nessie would choose work over her friend’s generosity. The story reinforces middle-class Victorian values: when in financial need, women should earn money by suitable work rather than accept charity, however well intended. In ‘Miss Mignonette’ by E.M. Hordle, a short story in the same extra Christmas issue, the eponymous heroine, who is alone in the world, teaches music and plays organ at Wychley Church.

In ’Miss Pringle’s Pearls’ by Mrs G. Linnaeus Banks in Volume 9, Aunt Phillis Penelope Pringle substitutes as organist at Shepperley Church, while in La Petite’s ‘A Disguised Blessing’ in Maidenhair, the extra summer number for Volume 13, Damaris Calendar, Hazelcopse’s new schoolmistress, takes on the organist duties on Sundays and forms a choir from her musical scholars and older parishioners.

Reginald Horton and Alec Hood both are in love with organists. Reginald, a farmer’s son in ‘A Love Out of Tune’ by J.F. Rowbotham, leaves home to pursue a career as a pianist. After a rocky start, his eventual success is a hollow victory when his father dies suddenly, greatly in debt. After promising to marry Reginald once he had made his name in music, Mildred Vane, the rector’s daughter and an organist, marries someone else. [Volume 17] Alec, in E. Tissington Tatlow’s ‘The Chapel by the Sea’, is more fortunate in love. Hearing ‘the sweet sound of an organ in a church close by’ makes Alec Hood feel sad, for he loves the organist, Laura Tressilian, and is afraid his past will make it impossible to win her. [Volume 28, p. 776] An act of bravery for which a medal is earned, as well as his recently deceased father’s estate, leads to Alec’s marriage to Laura in the Chapel by the Sea.

Most of the magazine’s organists were fictional; TGOP rarely mentioned living women organists. In ‘The Girl’s Outlook; or, What Is There to Talk About?’ by James and Nanette Mason, a self-improvement series in Volume 16, three friends in a remote village, all in their early twenties, meet at least monthly to discuss what they have read, confining their conversation to current topics and events, including musical ones. At one meeting they discuss the life of British organist Elizabeth Stirling (1819–1895) who had died recently. Stirling had made a name for herself as a publicized recitalist particularly of the works of Bach, as a church musician in a City of London church and as a composer of organ music. **

In a portrait of Her Majesty the Queen of Romania reprinted in Volume 26 of the magazine, the Queen is playing a large pipe organ. Only one article featured a living woman organist: Emily Lucas, a clergyman’s daughter who was blind since an early age, earned distinction as a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists. In her 1904 autobiographical account ‘A Blind Girl Organist’ in Volume 25, Lucas writes about the challenges and rewards of training a choir and playing for services at Saint Andrew Norwood when visually impaired.

Like the banjo, the organ disappeared from the pages of TGOP after the brief sketch of Lucas. An organist was featured in Volume 31, but the spotlight was on Sir Frederick Bridge, then organist of Westminster Abbey, as author. Women organists still were an item in Britain, but TGOP no longer featured them in fiction, and the magazine had ceased to print the Answers to Correspondents column with replies to the organists among its readers. More information about Britain’s women organists is found in Elizabeth Stirling and the Musical Life of Female Organists in Nineteenth-Century England, especially Chapter 2 ‘Ladies Not Eligible?’.

* Complete citations may be found in Judith Barger, Music in The Girl’s Own Paper: An Annotated Catalogue, 1880 – 1910 (Routledge, 2017).

** See Judith Barger, Elizabeth Stirling and the Musical Life of Female Organists in Nineteenth-Century England (Ashgate, 2007).