A series of blogs identifying five general categories of the nurse character’s role in operas from the mid-seventeenth through the early twenty-first century. The categories are fluid and overlap, so that the nurse character can and usually does appear in more than one category within an opera. Taken from a careful study of librettos and available performances of a hundred-plus operas with at least one nurse character.

Comic Nurses: Arnalta and Nutrice

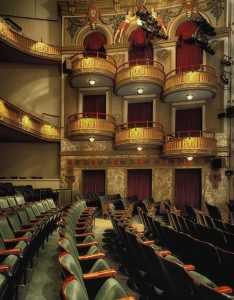

The Coronation of Poppea by Claudio Monteverdi, Libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello

Premiered in Venice, 1643

PART 1

Poppea Sabina has set her sights on Emperor Nero. Having divorced her first husband, she now is married to Marcus Salvius Otho, a close friend of the Emperor. Otho’s talk about his beautiful wife has caught Nero’s attention, and soon Poppaea and Nero are involved in a passionate, adulterous affair. Poppea’s nurse Arnalta tries to warn her mistress about the consequences of her amorous actions, but Poppaea takes no heed, choosing instead to focus on becoming Nero’s wife and Empress. That Nero currently is married to Octavia is no barrier for the scheming Emperor who simply decides to divorce her. In her counsel to the soon-to-be jilted Empress, Octavia’s nurse Nutrice advises revenge by taking a lover. Like Poppea, Octavia rejects her nurse’s advice, however, in this instance in favor of a virtuous if loveless life.

As historical figures, Octavia, Poppea, and Nero are familiar to audiences. The two nurses in the opera, however, are ahistorical, although Poppea and Octavia likely would have had nurses throughout their lives. Arnalta and Nutrice may have had their source in the nameless nurse in the Roman historical drama Octavia, for in the drama and in L’incoronazione di Poppea, a nurse advises both Octavia and Poppea in matters of the heart and shows her pragmatic nature. 1

But the operatic nurses also have roots in the commedia dell’arte – an improvisatory theatrical form that flourished in Europe from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries – whose troupes did not limit themselves to comic scenarios, but also performed tragic, pastoral, and royal scenarios. 2 Thus precedent was set for Arnalta and Nutrice to show a more serious side of their role as well as the stereotypical comic role. That serious side is reflected in the advice that the nurses give. Eric Chafe notes that although the two nurses represent the same comic stock character, the juxtaposition of their musical interactions in Act 1 scenes 4 (Arnalta and Poppea) and 5 (Nutrice and Octavia) in which each nurse gives contrary advice to her mistress, highlights the two women’s contrasting states of mind. 3 Because Arnalta and Nutrice are the nurses for the two respective leading ladies, I consider them separately, beginning with Arnalta, Nurse to Poppea, Act 1.

Much is made of Arnalta’s age and appearance in opera productions. Richard Taruskin describes her as “a ghastly crone.” 4 Thus from cast lists and operatic writings, the impression formed of Arnalta is someone of advanced age. But old is a relative term. Jeffrey Henderson notes that in fifth-century A.D. Attic Greek comedy, a woman was considered old once she had passed the age of childbearing and overt sexuality. 5 Traditionally wet nurses were between twenty and thirty years old when they began association with their nurslings; as companions and chaperones to their grown nurslings, Arnalta and her colleagues likely were middle aged – still relatively young by current standards, but past their prime of life in the seventeenth century. They were, however, old enough to wax nostalgic about their earlier years when men found them attractive and they had their share of lovers. Rodolfo Celletti writes of Arnalta, for instance, “now an old hag but at one time, as she confesses, a vivacious and hot-blooded woman.” 6

Arnalta sings in eight scenes, making her first appearance in Act 1 scene 4 when listening to Poppea thank Hope for the pleasures she is sure to enjoy as Nero’s lover and eventual wife. Although success in her mission is not guaranteed, Poppea is confident. “I fear not, no, no, no, … I fear no harm, no harm that may betide me,” she sings in a fast-paced repetition of her optimism. Monteverdi’s use of stile concitato signifies “the noise and excitement of battle, and by extension the emotional upheaval of love.” 7 Poppea’s harmonic rhythm slows to a march-like pace as her mantra changes to the assertion, “Love is my champion and fights my foe.” If Hope cannot guard her, Poppea says, she will prevail “with Fortune, Fortune on guard beside me.”

The eleven-measure sinfonia that follows introduces Arnalta, who fears the outcome of the young woman’s schemes. “Ah, daughter, daughter, pray to heaven / That all these sweet embraces turn not to danger and to your fatal downfall!” the nurse pleads. Poppea’s reaction is to interrupt her nurse with a repetition of her impetuous bravura of fearing not, now enhanced musically with a melismatic emphasis on the word “not”. Arnalta tries a different tack. Because Empress Octavia knows about Nero’s affair, the nurse worries for Poppea’s safety. Poppea counters with a repeat of her march-like determination that Love and Fortune are on her side. “Who meddles with a monarch espouses danger,” Arnalta tells her young charge, with a slow, dramatic step-wise descent on “espouses danger” to emphasize the seriousness of the situation.

Poppea’s music interrupts Arnalta five times, creating the effect that Poppea refuses to listen. A short ritornello lets Arnalta catch her breath before her next attempt to discourage Poppea from her dangerous liaison with Nero. Nero’s love is merely a diversion – a game – that he can end at will. But Poppea is still deaf to her nurse’s reasoning. Nero will drop you, Arnalta states more directly, “And leave you shame and scandal in compensation.” Throughout the two women’s exchange thus far, Arnalta’s tessitura contrasts with Poppea’s vocal range an octave higher. Only when Poppea sings in her “marching” mode does her voice enter her lower register.

After the next ritornello, Arnalta is losing her patience. If you proclaim that the Emperor loves you, she says to Poppea, it is not only “shameful” but “useless,” since nothing will come of it. “Give me for pref’rence those sins which make a profit,” the nurse concludes. Another ritornello, and Arnalta is like a dog with a bone. Marriage to Nero will be your undoing, she tells Poppea. Not surprisingly, Poppea still is not listening to her nurse’s advice. “No, no, … I fear no harm that may betide me,” she again sings.

With her preference for profitable sins, Arnalta is beginning to show her true colors, her “emerging immoral core,” according to Ringer. By now, he suggests, on the nurse’s sixth try to convince Poppea to change her ways, the audience realizes that Arnalta’s “admonitions mask a character nearly as unscrupulous as the mistress she reprimands.” 8 The nurse, it seems, is relying on the age-old maxim, Do as I say, not as I do, and holding her mistress to a higher standard. After overhearing Ottone bemoan his alienation from Poppea in Act 1 scene 11, for example, in scene 12 Arnalta expresses sympathy for his plight and reveals how she handled similar situations in her own past: “When I was young / I didn’t leave my lovers / to drown in tears: / being tenderhearted, I pleased all of them.” 9

On her seventh try, Arnalta takes on a more maternal tone when she warns, “Careful, careful, Poppaea!” The nurse offers the analogy of a snake lurking in the pleasantest meadow or greenest grass – a clear reference to the Garden of Eden and Adam and Eve’s fall from grace, and the calm before the storm. Tears are certain to follow Poppea’s present laughter, Arnalta fears. After her musical circling about the snake in the grass, Arnalta’s harmonic rhythm gradually increases when singing of the approaching storm, stressing her increasing concern for Poppea.

But Poppea is adamant: “Arnalta,” she addresses her nurse using her name for the first time, “I fear not, I fear no harm that may betide me.” She still is willing to put her trust in Fortune to guard her in this affair. Although the tessitura of Poppea’s persistent refusal to listen to her nurse’s advice has not changed, the young woman emphasizes her fearlessness in a string of high notes not yet heard in her argument.

At last, Arnalta gives up. “Oh, you’re crazy, yes, you’re crazy!” she tells stubborn Poppea. Anyone who would be so stupid as to put her trust in “bald old Lady Luck and blinded Cupid” is indeed crazy, the nurse declares as she exits the stage, perhaps tossing her hands up in despair – but with true concern for the sorrow that her nursling will endure in the end. each dyad and sets the stage for the events that follow.

A comprehensive list of the hundred-plus operas that include a nurse character is found on my website under BOOKS > The Nurse in History and Opera > Book Extras.

To learn more about how the nurse is portrayed on the opera stage, see Judith Barger, The Nurse in History and Opera: From Servant to Sister (Lexington Books, 2024).

Notes

- The cast list for Octavia found in Frank Miller’s edition of the work lists only one nurse, for Octavia, but Ferri identifies two nurse characters in his edition of the drama. See Rolando Ferri, ed., Octavia: A Play Attributed to Seneca (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Richard Andrews, Scripts and Scenarios: The Performance of Comedy in Renaissance Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 171. See also Flaminio Scala, Scenarios of the Commedia dell’Arte: Flaminio Scala’s Il Teatro delle favole rappresentative, trans. Henry F. Salerno (New York: New York University Press, and London: University of London Press, 1967).

- Eric T. Chafe, Monteverdi’s Tonal Language (New York: Schirmer, 1992), 318.

- Richard Taruskin, Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 2, Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 27

- Jeffrey Henderson, “Women in Attic Old Comedy,” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1987) 108.

- Rodolfo Celletti, A History of Bel Canto, Frederick Fuller (Oxford: Clarendon and New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 35.

- Unless otherwise indicated, lyrics are from Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea (The Coronation of Poppaea) [vocal score], ed. Alan Curtis (London: Novello, 1989); Robert C. Ketterer, Ancient Rome in Early Opera (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 29.

- Mark Ringer, Opera’s First Master: The Musical Dramas of Claudio Monteverdi (Plumpton Plains, NJ: Amadeus, 2006), 235.

- Claudio Monteverdi, L’incoronazione di Poppea, The English Baroque Soloists, cond. John Elliott Gardiner (Archiv Production CD libretto), 121.