The Aerial Nurse Corps of America

Part 7

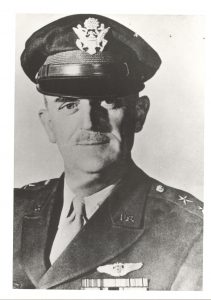

Undeterred by the American Nurses Association (ANA) rejection of the Aerial Nurse Corps of America (ANCOA), Schimmoler again set her sights on military support of the ANCOA. In July 1942, with approximately 400 of her ANCOA nurses on duty with the armed forces, Schimmoler corresponded with Brigadier General David N. W. Grant, Air Surgeon for the Army Air Forces, United States Army:

David N.W. Grant, Air Surgeon, Army Air Forces [USAF Photo]

David N.W. Grant, Air Surgeon, Army Air Forces [USAF Photo]

Frankly, General, I have almost begun to think that I am another Billy Mitchell. I have not, however, given up hope that some how some way that your department will embark upon the creation of a school for nurses for air ambulance duty and that we [ANCOA] might be accorded the consideration of doing our part in the operations of this school. I feel this department should be separate apart from the regular Army Nurse Corps and be attached as a special unit of the Air Forces. …

There isn’t a question in my mind, with the interest there exists in this field, that if we had the support and authority needed, that we could create an Air ambulance unit that you could well be proud of. 1

In his reply Grant informed Schimmoler that

The question of aerial evacuation with the armed forces is now in the formative stage. Nurses will be assigned from the Army Nurse Corps for this work. Many nurses who have had prior experience with the airlines are available for this purpose. Evacuation, as contemplated, is of the mass type during actual combat.

There are many vacancies in the Army Nurse Corps, which members of your association can join. Nurses are not being recruited specifically for aerial duty, but are being earmarked for this duty when the need arises. …

I hope this answers your question. 2

A month later, Grant and members of the Army Surgeon General’s Office accepted a plan for a workable air evacuation system designed by Colonel Wood S. Woolford, the first Air Transport Command (ATC) Surgeon. Grant submitted the plan to the Air Staff in July 1942 and received approval to begin its implementation. Because of a shortage of airplanes, the plan incorporated the evacuation of casualties into the duties of the Troop Carrier Command whose tactical mission was to fly men and equipment into combat areas and of the ATC responsible for strategic flights between overseas locations and the United States. These transport planes, when outfitted with litter installations, could be converted into air ambulances for the return trip once troops and cargo were offloaded, putting to humanitarian use planes that would have returned to their bases empty. An interesting feature of Woolford’s plan was the employment of 103 female flight nurses. 3 At the time, only females served as Army nurses. Although the Army had male nurses, they were not commissioned as officers but rather were classified as nurses at the induction centers and assigned in the Medical Department of the Army as enlisted medical technicians. 4 Like the Army nurses assigned to ground medical facilities, the flight nurses would hold the relative initial rank and wear the insignia of second lieutenant. Not until 10 July 1944 did a presidential Executive Order appoint nurses as commissioned officers of the United States Army with the corresponding rights, benefits, and privileges accorded male officers.

Over the next five months, events happened quickly in the development of the air evacuation system in which Army flight nurses would participate. In September 1942 the 38th Medical Air Ambulance Squadron, a “paperwork” organization initially numbering only one officer and a few enlisted men that had been activated at Fort Benning, Georgia the previous May, was transferred to Bowman Field in Louisville, Kentucky. Bowman Field was chosen because of its proximity to the First Troop Carrier Command headquarters in Indianapolis just over a hundred miles north and because it already had some facilities in place as the former site of the Medical Officer Training School. 5

Upon its arrival, the squadron, now counting two officers and 138 enlisted men among its personnel, was assigned to the First Troop Carrier Command, which had been delegated responsibility for organizing and training air evacuation groups, and was attached to the base hospital. The 38th Medical Air Ambulance Squadron, which became part of the Army Air Forces, was re-designated the 507th Air Evacuation Squadron, Heavy, three days later and served as the nucleus for the air evacuation system. Flight nurses were among the 507th personnel. The 349th Air Evacuation Group activated at Bowman Field on 7 October incorporated the 507th Air Evacuation Squadron, Heavy, and three new units – the 620th and 621st Air Evacuation Squadrons, Heavy, and the 622nd Air Evacuation Squadron, Light, all activated on 11 November. 6 “Heavy” squadrons were those that would fly multi-engine cargo transport planes; the “Light” squadrons were to have their own smaller single-engine airplanes capable of carrying no more than three patients. The “Light” squadron idea was abandoned eventually, because these planes were going to the Navy rather than to the Army Air Forces. 7 Table of Organization 8-447 issued in tentative form in November 1942 and finalized in February of the next year established the Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron with a headquarters section that included commanding flight nurse and chief nurse; and four evacuation flights of six flight nurses and six enlisted surgical technicians, each flight commanded by a flight surgeon. Flight teams consisting of one flight nurse and one surgical technician were to be placed aboard transport planes as needed, and when personnel were short or when casualty loads exceeded available teams, the flight nurse and the surgical technician could fly in separate planes. 8

The Army Surgeon General, who was always short of nurses, opposed the decision to use female flight nurses, but the Air Surgeon felt that flight nurses should be used in the air evacuation program, since they were the most highly trained medical personnel available for these missions. After the war, Colonel Erhling Bergquist, who had been Command Surgeon for the Ninth Troop Carrier Command and later for the First Troop Carrier Command in Europe during the war, defended the decision: “We felt that if in this country a group of healthy individuals could fly around in commercial airlines having a nurse attend them, our wounded certainly were entitled to the same consideration.” 9 He was referring to the airline policy before the war to hire only registered nurses as flight attendants. When the need for nurses to work in civilian hospitals and to serve in the armed forces became urgent during World War II, the airlines substituted college education for a nursing diploma as a prerequisite for work as a stewardess. 10

During the months when the air evacuation program was being organized, the Office of the Air Surgeon received letters from nurses inquiring about air evacuation duty. United Airline stewardesses from California, a nurse from New York who was working toward her private pilot’s license, nurses from Georgia, Louisiana, and Nebraska, and a congressman in Washington, DC – likely on behalf of some of his constituents – all wrote to the Air Surgeon to request applications for and particulars about this new field of nursing. Replies contained essentially the same information: All nurses for air evacuation units would be obtained from nurses of the Army Nurse Corps, and to be eligible for air evacuation duty, a nurse must enter the Army Nurse Corps through the usual channels. Nurses were not accepted exclusively for air ambulance work, but volunteers would be assigned to this duty at a later date when the need arose. War Department Memorandum No. W40-10-42 dated 21 December 1942 spelled out the qualifications for air evacuation nurses and the application procedure to be followed. Only those applicants who were members of the Army Nurse Corps would be favorably considered. Applicants had to be twenty-one to thirty-six years old with a weight between 105 and 135 pounds, had to be physically qualified for flying, and had to certify willingness “to be placed under orders requiring frequent and regular participation in aerial flights”. 11

Starting in October 1942, marriage did not make a nurse ineligible for military service. Single nurses who married while on active duty remained in the military at the discretion of the Surgeon General and, generally speaking, only physical disability and incompetence were grounds for dismissal. By the end of the year, married nurses who met all other requirements for military service could join the Army Nurse Corps. Every nurse agreed to serve for the duration of the war plus six months. By default, a married nurse retained her maiden name while in service unless she specifically requested a name change. 12

As the war continued, the need for an air evacuation system overseas became more urgent. At Bowman Field on 10 December 1942 the 507th, 620th, and 621st Aeromedical Evacuation Squadrons, Heavy, were re-designated the 801st, 802nd, and 803rd Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadrons [MAETS] as outlined in Table of Organization 8-447. 13 The 801st and 802nd squadrons, which included flight nurses among their members, were hastily trained in the essentials of air evacuation – an “admittedly meager and inadequate” preparation for the work ahead. 14 One 802 MAETS flight nurse recalled that at Bowman Field

The curriculum was nowhere near complete – except for Chemical Warfare – “GAS will be used in this war” was repeated time and again and with emphasis by Captain Gray – and we learned all there was about the recognition of the various gases, how to put on a gas mask and how to treat patients who were contaminated. That class, physical exercises, and marching rounded out our brief education. 15

On Christmas Day 1942 the first of these squadrons, the 802 MAETS, departed Bowman Field for North Africa to provide air evacuation support for the Tunisian Campaign. 16 Former stewardess Ellen Church, now recovered from an automobile accident and a lieutenant in the United States Army, was among the flight nurses in that organization. 17 Just over three weeks later the 801 MAETS left Bowman Field for the South Pacific where American troops were still engaged in the battle of Guadalcanal. 18 Flight nursing in the United States Army Air Forces had become a reality.

To be continued

Notes

1 Lauretta M. Schimmoler, letter to David N.W. Grant, 24 Jul 1942.

2 David N. W. Grant, letter to Lauretta M. Schimmoler, 3 Aug 1942.

3 Wood S. Woolford, letter to Victor A. Byrne, 17 Jul 1942. [AFHRA 280.93–5]; “History of the School of Air Evacuation,” 1 Aug 1943, 2-4. [AFHRA 280.93–3]; “History of the School of Air Evacuation,” n.d., in “School of Air Evacuation,” Army Air Base, Bowman Field, KY, 9 Dec 1940–Apr 1944; Jan 1944–Jun 1945, 1-3. [AFHRA 280.93–12 v.2]; Robert F. Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation in the USAF, 1909–1960. Historical Studies No. 23 (Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University; Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs/Aerospace Historian, 1960), 73–74.

4 “Men Nurses and the Armed Services,” American Journal of Nursing 43 (Dec 1943): 1066–69.

5 Mae M. Link and Hubert A. Coleman, Medical Support of the Army Air Forces in World War II (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1955), 367.

6 “Medical History, I Troop Carrier Command,” 30 Apr 1942–31 Dec 1944, 50–52. [AFHRA 250.740]

7 Ibid.; “History of the School of Air Evacuation,” 1 Aug 1943, 2–4. [AFHRA 280.93–3]; Futrell, Aeromedical Evacuation, 73–74.

8 Frederick R. Guilford and Burton J. Soboroff, “Air Evacuation: An Historical Review,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 18 (Dec 1947): 609; Futrell, Aeromedical Evacuation, 78–79; “Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron,” Table of Organization No. 447, War Department, Washington, DC, 15 Feb 1943.

9 Erling Berquist [Ehrling Bergquist], “Discussion,” in David N. W. Grant, “Air Evacuation Activities,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 18 (Feb–Dec 1947): 182–83.

10 “Fly Again!” RN (Dec 1945): 40; “Nurses Released From Airline Positions,” Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 108 (Mar 1942): 207–208; “Discontinued for the Duration,” Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 108 (Apr 1942): 268; “War-Time Needs Come First,” American Journal of Nursing 42 (Apr 1942): 449–50; “Airline Nurse Stewardesses Released,” American Journal of Nursing 42 (May 1942): 577–78.

11 “Nurses for Air Evacuation Service,” Memorandum No. W40-10–42, War Department, Adjutant General’s Office, 21 Dec 1942.

12 “Married Nurses Retained in the Army,” American Journal of Nursing 42 (Nov 1942): 1322; “Married Nurses for the Army Nurse Corps,” American Journal of Nursing 42 (Dec 1942): 1451; “Married Nurses in the Army,” American Journal of Nursing 43 (Apr 1943): 306.

13 “Post Diary,” Air Base Headquarters, Bowman Field, Louisville, KY, Dec 1940–Aug 1945, 49. [AFHRA 280.93–1]

14 Futrell, Aeromedical Evacuation, 80.

15 Clara Morrey Murphy, “First unabridged rough draft of Symposium speech, Nov 12, 1992, 50th Anniversary.” [AMEDD]

16 “Medical History, 802nd Medical Air Evacuation Squadron,” 10 Dec 1942–30 Jun 1944, [1]. [AFHRA MED-802-HI]

17 Church, who had been chief stewardess for Boeing Air Transport for eighteen months, was grounded following an automobile accident.

18 “Post Diary,” Air Base Headquarters, Bowman Field, Louisville, KY, Dec 1940–Aug 1945, 51. [AFHRA 280.93–1]