From Chickens to Flying:

Lauretta M. Schimmoler and

the Aerial Nurse Corps of America

Thanks to Robert E. Skinner’s meticulous research from the 1980s, we know much about the life of civilian pilot Lauretta M. Schimmoler, founder of the Aerial Nurse Corps of America (ANCOA). His 1984 article “The Roots of Flight Nursing: Lauretta M. Schimmoler and The Aerial Nurse Corps of America” introduced a worldwide aeromedical audience to the accomplishments of this visionary pilot from Ohio who in the 1930s identified flight nurses as the key to a successful program of medical air evacuation in time of national emergency. 1 When writing Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II (Kent State University Press 2007), I was familiar with Skinner’s work, having met and corresponded with him many years before during my Air Force career. Since the book’s publication, I have had an opportunity to review some of the sources in Skinner’s own research files at the Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, AL that shed new light on my own research.

This blog elaborates on some points that I made in Chapter 1 Origin of Flight Nursing in Beyond the Call of Duty and in eight blogs about Lauretta Schimmoler that I posted on my website from 1 Oct 2018 through 16 Mar 2019.

Pilot Lauretta M. Schimmoler, circa 1932 [Bucyrus, OH Historical Society]

ANCOA and State Nurses Associations

The California State Nurses’ Association (CNSA) was one of the organizations that Lauretta Schimmoler, who lived in Los Angeles, approached around 1940 when seeking recognition of her Aerial Nurse Corps of America. In a salvo of correspondence begun in 1937 the American Red Cross (ARC) and the American Nurses Association (ANA) decried and dismissed any connection between CSNA and ANCOA, because Shimmoler had not sought permission to link her organization with the ARC First Reserve – and, perhaps even more egregious – because she was not a nurse, Schimmoler dismissed their objections, however, when In the first issue of the short-lived Nurses’ Aeronautical Digest she wrote:

It is with a warmth of gratitude that the NURSES’ AERONAUTICAL DIGEST acknowledges this month the stimulating cooperation given the Aerial Nurse Corps of America by the California State Nurses’ Association. To these good nurses WE DEDICATE THIS FIRST EDITION OF OUR NEW PUBLICATION. To them goes much credit, for they have helped us in promoting understanding among the nursing profession. They have tended by their very actions to make the Aerial Nurse Corps of America a cohesive whole, instead of a divided organization. Their patience and inspiration explain much of the recent progress displayed by the Corps. 2

NURSES’ AERONAUTICAL DIGEST was intended to replace the monthly mimeographed ANCOA Flashes that had shared the organization’s news with its members for three years. In the new format, Schimmoler reviewed the achievements of ANCOA over the past years:

1932 Dec Inception, Cleveland, OH

1936 Sep First official assembly for organization, Los Angeles, CA

1937 Jan Foundation of organization

1938 Jan Incorporation of organization

1938 Feb Copyrights

1938 Jul Recognition by National Aeronautical Association

1940 Jan Confirmation by resolution, National Aeronautic Association

During 1939, ANCOA was recognized through State Nursing Association Advisory Council appointments in California, Ohio, and Michigan; it is this activity with which the national leaders of the ARC and ANA took issue. 3

Continuing her progress report, Schimmoler noted establishment of fifteen active companies of ANCOA nurses, and members’ voluntary participation in first aid stations at air meets and air events treating over 3,000 persons.

Although begun as a civilian organization, Schimmoler clearly intended that her nurses eventually would form the military flight nurse cadre as ANCOA nurses:

We have a niche to fill, namely, ONE – in Aviation, TWO – MOBILE MEDICAL EVACUATION BY AIR AMBULANCE. THREE – the formation of adequate personnel to fill a vacancy and the creation of a new department established in such a manner as to dovetail into the existing service organizations so as to create for them a Department of Service, which they can immediately call upon to fill the needs in aviation. Aerial Nurses and their auxiliary departments are not encroaching upon assignments of any other persons, but filling a niche which will be invaluable in time of need.

An Aerial Nurse Corps company is so designed to be capable of carrying out the assignments of any of the National Emergency Service organizations, civil or military.

Standards for enlistment have been so established as to comply with the requirements of the organizations of which it would otherwise come under the direction. 4

ANCOA Pilots from Ninety-Nines, Inc.

Three years before the Women Airforce Service Pilots – WASP – organization was established in August 1943 to ferry planes for the US military, ANCOA founder Lauretta Schimmoler had proposed a corps of qualified women pilots to transport ANCOA flight nurses and their medical supplies to areas of need during time of emergency. In a letter to the Ninety-Nines, Inc. International Organization of Women Pilots of which she was a member, Schimmoler outlined her idea, which Mrs. Fanny Leonpacher, editor of the Ninety Nine News Letter, printed in that publication of May 1940. “President Schimmoler wishes to give the members of the Ninety-Nines an opportunity to become identified with this new Section” – the Air Corps Reserve Section of ANCOA – wrote Leonpacher, who included an excerpt from Schimmoler’s letter:

The work of this Section would, of course, be confined to those woman pilots who have the qualifications to pilot four place or larger aircraft under varying conditions. In the event of emergency and it is necessary for us to have medical supplies or personnel transferred from one point to another, we will have available the list of eligible who can get into equipment and conduct such an activity. 5

Leonpacher then asked interested readers to contact Shimmoler directly at 2620 N. Hollywood Way, Burbank, CA.

It is intriguing to consider the possibility that as a civilian Schimmoler had pictured women pilots’ contribution to the war effort a few years before military leaders acknowledged their usefulness in the Army Air Force’s ongoing campaign to control the skies. And in Schimmoler’s mind it could have been a logical next step for Ninety-Nine, Inc. pilots to move from ferrying flight nurses and medical supplies to transporting sick and wounded soldiers on air evacuation missions.

ANCOA Ground Activities

Serving as volunteers in first aid stations at air events and air shows gave ANCOA members an opportunity to participate in aviation activities on the ground when work as a nurse aboard aircraft was limited. A 31-page First Aid Duty manual that Schimmoler prepared and printed in 1939 outlined the nurses’ responsibilities in setting up and running First Aid stations. “Aviation needs nurses as do other industries,” Schimmoler wrote, “ and to be efficient in this specialized phase of the industry it is essential that every nurse be trained.” Schimmoler wanted to instill excitement in the “scientific work ahead in the field of Aviation” that a nurse’s affiliation with ANCOA would make possible. “In this Manual we wish to go on record as being the first in the United States to indicate sufficient interest in our men and women in aviation to want to give them the best care possible at all Air Events,” Schimmoler wrote. She purposely made no reference to nursing technique or knowledge, relying on each ANCOA nurse’s training to prepare her for required first-aid duties she might need to render.

Schimmoler concluded:

These pages have been intended to bring out thoughts for the purpose of inciting a new zeal in your hearts and a burning desire to want to do YOUR part in this new industry. A desire to shun the glamour and accept the seriousness of it all. …

It is my hope that your Motto will be as mine has been . . . . “Whether I know him or not if he flies, he is a friend of mine in Aviation and if anything should happen, The Best is none too good”. . . . Give him the best available, Do not be satisfied with anything, do not be too hasty in your actions. Be thorough but always keep in mind, The Best Is None Too Good”. 6

Schimmoler’s Belated Recognition

When Lauretta Schimmoler initially contacted General Hap Arnold, Chief of the Air Corps, about her flight nurse organization in hopes that he could see its military usefulness in time of war, Arnold expressed an interest that, on further intelligence from his staff, he chose not to pursue in favor of the military’s continued cooperation with the ARC to obtain nurses for military needs. Not everyone on Arnold’s staff discounted ANCOA’s possible role in national defense, however. Writing in 1966 to Matilda Grinevich, a prior ANCOA nurse and World War II flight nurse who made the Air Force a career and retired as a lieutenant colonel, Colonel J.L. Stromme, who had served in the Assistant Secretary of War office prior to transfer to Los Angeles where he met Schimmoler in 1938, recognized her great contribution to “Flying Nurses.” “Those of us who knew [her, knew] of her zeal to have the sick and wounded given speedy transportation to the Hospital best qualified to treat the case in hand, which, in many cases would be by air.” Stromme told Grinevich that he had spoken to Arnold many times, urging him to take advantage of Schimmoler’s work, “and give her recognition for the part she played in its development. He said he would, but he never did, not even a letter to her.”

Stromme, whose letter contains many typos, continued:

There is a poem which goes something like this:

If, with pleasure, you are viewiny [sic]

The work some on[e] is doing, Tell her now.

Don’t with[h]old your approbation

‘Till the Parson makes oration

And she lies with lilies on her brow,

For no matter how you shout it,

She won[‘]t care a thing about it

For she cannot read her tomb-stone when she’s dead.

Which is all too true, none of us is so familiar with the dead language that we will be able to read our epitaph.

Through your efforts you have made Life much brighter for Loretta [sic], she is so grateful. 7

Grinevich had known Schimmoler since the 1930s when organizing the New York Unit of ANCOA; soon one of the first Army Air Force flight nurses of World War II with follow-on participation as an Air Force nurse in the Korean and Vietnam Wars as well, Grinevich well knew how air evac saved the lives of combat casualties. For years she fought to have Schimmoler recognized as originator of the flight nurse concept – with no success until 1966.

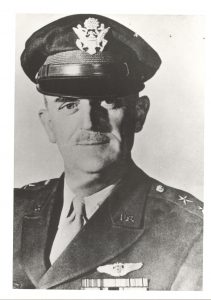

At the Flight Nurse Section’s third annual luncheon during the Aerospace Medical Association’s annual meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, USAF Surgeon General Lt General Richard Bohannon presented Lauretta Schimmoler, whom he introduced as “The Billy Mitchell of the Flight Nurses,” with a plaque, an Honorary US Air Force Flight Nurse Certificate, and a pair of flight nurse wings. 8 Lt Colonel Grinevich, who was in charge of the luncheon arrangements, was on hand to see her hard-fought battle on behalf of Schimmoler finally bear fruit.

Two years later in January 1968, Schimmoler, pictured below, was an honored guest at a banquet at Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio, TX celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of flight nursing that began in the Army Air Forces and continued in the US Air Force.

Captain Nancy Barran (L) and Lauretta Schimmoler (R) [USAF Photo]

Captain Nancy Barran (L) and Lauretta Schimmoler (R) [USAF Photo]

Schimmoler After ANCOA

As World War II continued, Schimmoler closed her ANCOA offices in Burbank, CA, and in 1944 enlisted in the Army as a WAC. After basic training in Iowa, Private Schimmoler returned to California for duty as a dispatcher in base operations on the flight line at Fairfield-Suisun Army Air Base – later renamed Travis Air Force Base. On duty when the first C-54 Skymaster air evacuation flight with its sick and wounded soldiers arrived from the Pacific theater of operations, Schimmoler saw her dream become a reality.

Following her military service, Schimmoler returned to civilian life as a detective with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department – with which she had been associated before the war – for sixteen years before retiring in 1964.

Grinevich thought that Schimmoler, whose eyesight had begun to fail even before her “recognition” in 1966, had had a premonition for a long time of her days being numbered before her death in 1980. Writing to Robert Skinner in 1982, Grinevich recalled that Schimmoler, who lived in Glendale, CA, had pulled out a new formal from her closet that she described to Grinevich as her shroud in which she wanted to be buried. Schimmoler had a transient ischemic attack in October 1980 followed in three days by a massive stroke that took her life three months later at age 80. 9 After funeral services in her hometown of Bucyrus, OH, Lauretta Schimmoler was buried at Holy Trinity Cemetery, less than a block from where she had raised chickens before taking to the skies.

Notes

1 Robert E. Skinner, “The Roots of Flight Nursing: Lauretta M. Schimmoler and The Aerial Nurse Corps of America,” Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine 55 (1) (Jan 1984): 72–77.

2 “Editorial,” Nurses’ Aeronautical Digest 1 (1) (Oct 1940): title page.

3 “Progress,” Nurses’ Aeronautical Digest 1 (1) (Oct 1940): 7.

4 Ibid.

5 “Nurses,” Ninety Nines News Letter (May 1940): 2.

6 Lauretta M. Schimmoler, Aviation First Aid Duty (Aerial Nurse Corps of America National Headquarters, Burbank, Los Angeles, CA, 1939): I, 12, 31.

7 J.L. Stromme, letter to “Lt. Col. M.D. Grenevich” [sic], 23 Apr 1966.

8 “Miss Schimmoler Awarded Honorary Flight Nurse Certificate and Wings,” Aerospace Medicine 37 (7) (July 1966): 757.

9 “Mickie” Grinevich, letter to Robert Skinner, 4 Feb 1982.