The Twenty–second in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

Interlude: Living Conditions

The gorgeous mansion with formal gardens on an acre of land that the 815 MAETS flight nurses called home on their arrival in England, with its great entrance hall, spiral staircase, and marble fireplace, was the exception, not the rule for the assigned quarters that most of the MAETS flight nurses encountered overseas. The house was near the quaint village of Boxford with its thatched roofs, a church outside the gate, and a post office and pub nearby. On their arrival at RAF Greenham Common, the 816 MAETS flight nurses were surprised to find “a real house” waiting for them “with white sheets on the beds, dressers, and hot water for baths” – “and a flush commode’!”. 1 Accommodations at other RAF bases where the flight nurses were quartered, however, were more spartan. And quarters were no better in France.

Flight nurse Winna Jean Foley Tierney of the 806 MAETS recalled that after 3 months the squadron moved to Nottingham and Langar, an RAF base, “where we again established residence in the local [N]issen huts. These lovely domiciles were noted for their lack of insulation, lack of heat, lack of comfort, and plenty of air conditioning. Also, when it rained and the wind blew from a certain direction, they had a tendency to become flooded.” At Orly Field, the “lovely” building that the nurses “fell heir to! … had everything – except heat, hot water and window panes. (The warmest place was outside in the snow.)” 2

Boxford House, England (Author’s Collection)

Alice Krieble, who flew with the 818 MAETS, recalled that at the squadron’s first assignment in Spanhoe, England the 25 flight nurses lived in a Nissen hut, which was a wing of the hospital. “It was quite a life,” Krieble remembered. Alice and a friend found some boxes and made night tables to augment the cots and footlockers provided. The squadron stayed at Spanhoe for 2 months then moved to Cottesmore; the squadron history attributed the transfer to inadequate quarters for the nurses at their first station. 3

Because mess halls often were located some distance from their quarters, flight nurses in England were issued bicycles for transportation and for recreation. According to Grace Dunnam Wichtendahl, some girls in the 806 MAETS wouldn’t ride their bicycles, because they didn’t want to overdevelop those muscles, so for them it was a lengthy walk. But she had fun riding her bicycle, and that is how she got to chow. Carlson and her colleagues in the 815 MAETS rode around the countryside a lot and explored the little villages nearby. The bicycles were new to the flight nurses with their thin tires and hand breaks. Krieble decided, “I’d ride it or kill myself. I rode it – it was our only outlet.” 4

806 MAETS Geraldine Dishroon (center) and colleagues in England, 1943 (USAF Photo)

Prestwick, Scotland, where the flight nurses accompanied patients on flights back to the US, came with its own housing challenges. As June Sanders, historian for the 819 MAES, grumbled:

Ah – Westfield House by the Sea – A Menagerie of women, our keeper for the most of the month being an overbearing Sgt., who sadistically enjoyed making life as miserable as possible for everyone with whom he came in contact. He – accompanied by over-crowded rooms, oversized rats, over-drafty ventilation, over-active fleas, too few bathrooms, – combined to completely disillusion us in regards [to] old Scottish Castles. 5

Blanche Solomon Creesy, who flew with the 822 MAETS on the North Atlantic route, had her own tale of the flight nurses’ bathroom woes in Newfoundland when

they had us in the same hallway as all the men, and we had to go out front in the Officers Club to bathe and do anything else we had to do. And they finally got rid of most of the men, but they still kept the big bathroom down the hallway. So that was when some of the kids – and I don’t think it was accidental, though it might have been, because we had 25 of us using one toilet, and it was really overused. And so when it kept flowing out into the Officers Club, they gave us a big bathroom. They finally moved the rest of the men out to another hallway. 6

Flight nurses in the 802 MAETS experienced a variety of quarters as they moved from North Africa to Italy as the drive toward Germany progressed. From Mud Hill near Oran, where they bivouacked on arrival overseas, they too progressed – to 2 small French villas with “atrocious plumbing” in Tunis, to a 3–story lighthouse keeper’s house on the bay in Licata, and on to an apartment building in Palermo, where the squadron’s mess hall was across the street from the opera house. Here the flight nurses went to Sunday matinees and returned to the mess hall for dinner during the intermission. In Naples the flight nurses were housed in a baroness’s villa on the bay, and on to Lido di Roma – a resort village that Mussolini had built. “Not much of a resort any more,” Clara Morrey Murphy wisecracked. 7 The flight nurses’ accommodations looked beautiful from a distance, but on closer inspection the retreating Germans had damaged the electrical system and plumbing, shattered the window glass, and had planted mines in the ground surrounding the building. Water brought in for bathing and laundry, and candles for light made the quarters livable until repairs could be made and a generator obtained. 8 Their last move was to the quaint walled city of Siena, a university town.

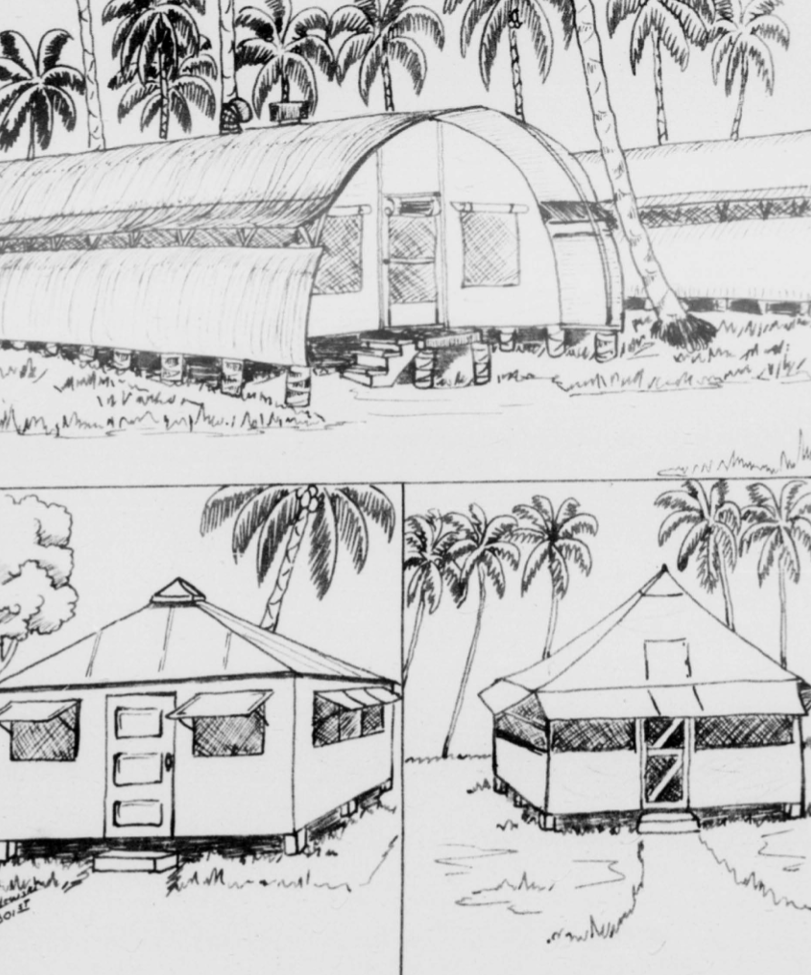

For many flight nurses, especially in the Pacific, prefabricated buildings offered a satisfactory living space after having resided “under canvas” – that is, in tents – initially. When in New Caledonia, the 801 MAETS flight nurses lived in tents for which they eventually obtained floors. Lee Holtz recalled the time that she returned from a flight to discover that “the tent or something had leaked, and all my clothes were wet. And I didn’t even have anything dry to put on. But we hung them all out. And we laughed about it. You couldn’t get upset about things. You just couldn’t. You couldn’t survive that kind of life. You really needed a sense of humor.” 9

In Espirito Santo the squadron campsite boasted 15 Dallas Huts, 4 Quonset huts, 2 New Zealand buildings, a large screened mess hall, 3 shower and wash rooms, and 3 screened latrines. 10 Usually the flight nurses were housed in a little compound with latrines in the middle, Holtz recalled, but on Biak they all lived in one big Quonset hut and had an outdoor latrine. Because stray Japanese soldiers still existed in the area, if a flight nurse needed to use the facilities late at night, she would go to the door and call for the guard who would walk her to the latrine. “I bet he loved his duty during the war,” Holtz quipped. 11

According to some flight nurses, Biak was the worst location for them in the Pacific because of the snakes – hanging from trees, in the bushes, in the shower room, even occasionally in their quarters; 3 flight nurses mentioned the snakes in interviews with the author. “Oh, I was so frightened of snakes and bugs and stuff,” Holtz said. “But we lived with them. There wasn’t anything else we could do.” Helena Ilic Tynan recalled that Burlap Flats was just one long building with the cubicles. “Every once in a while, you’d hear screaming” – a snake perhaps had gone over a flight nurse’s legs. “I absolutely hated Biak,” she declared. Adele Edmonds Daly remembered that Biak was “just like living on a reef, a coral reef. No plant life or anything around, really … it was just lying off this on the barren ground with the sun just beating on you all the time, it seemed. But there were snakes”. 12

It could have been worse, it seems. An unnamed flight surgeon of the 804 MAETS wrote of the tedious process of transforming “farmers, cowboys, carpenters, truck drivers and factory workers” who had been drafted into the military into medical technicians to whom the flight surgeons could entrust the nursing care of battle casualties. 13 But squadron commanders were often thankful for the diverse backgrounds of their enlisted men when setting up new campsites on Pacific islands. As Leopold Snyder, who headed a detachment of the 804 MAETS sent to Biak, reported, the men could do anything, based on their skills in civilian life. “Carpentering, construction, plumbing, blasting, wiring for electricity, running cement mixers all found someone able to handle the job. … I can excuse these men of many past and future sins after working thru this period with them.”14 The flight nurses, too, had enlisted men to thank for the “midnight requisitions” that brought them comforts of home.

801 MAETS Housing in the Pacific (AHFHRA)

The names that the flight nurses gave to their quarters in the Southwest Pacific – Burlap Flats (801 MAETS), Bickering Heights (804 MAETS) – suggest a good-humored acceptance of their primitive living conditions. Added domestic luxuries such as curtains, bedspreads, and rugs that could be secured “by methods sometimes orthodox and often more devious” added to the contentment of the nurses, and word apparently spread of their desire for more luxurious accommodations. 15 Flight nurses of the 801 MAETS were pleased to discover that “This lust for better homes has been picked up by our well–wishers everywhere and on nearly every island there is now tucked obscurely away, an overnight lodge for flight nurses, invariably bedecked, bedeviled and beguarded.” 16 The arrival of a washing machine was a welcome amenity long overdue for personnel of the 804 MAETS in New Guinea in January 1944. Flight nurse Dorothy Rice wrote Leora Stroup that the small kitchen in their quarters was the busiest spot in New Guinea “except perhaps our brand new washing machine”. 17

“Burlap Flats” flight nurse quarters on Biak (Author’s Collection)

The living situation was quite different at Hickam Field, Oahu. Although the flight nurse accommodations were less primitive than those of flight nurses on other islands, they were not up to the standards of 812 MAETS chief nurse Elizabeth Pukas. When she learned that she and her 24 flight nurses were to be housed in 2 3–bedroom houses, she went to the commanding flight surgeon and requested another house to make their accommodations more livable. When told that the housing was temporary, since her nurses would be out on flights much of the time, Pukas replied, “Yes, but there will be a number of us having to stay home in between flights to recuperate, to refurbish, to repack. … And I’m very sure you would not ask a male counterpart to live in such close quarters.” The nurses eventually were given more adequate housing, but not before their chief nurse had taken the situation through the chain of command to headquarters level. “I’m not too forward,” Pukas explained, “but I am a chief nurse. … My flight nurses are extremely important to me.” The amenities of home were also important to Pukas. Having obtained the third house eventually, she decorated the houses with paintings on loan from a local art museum and stocked the kitchens with good foods obtained from the nearby Navy commissary. Pukas was, she said, the flight nurses’ “surrogate mother”. 18

The 803 MAETS squadron spent their first few weeks in India setting up their living space with as many comforts of home as they could buy, build, or rig. Electricity, laundry facilities, and a shower all appeared thanks to the tireless work of men from the 803 MAETS and other friendly squadrons. Once living quarters were in satisfactory condition, the 803 MAETS turned its attention to recreational facilities. Badminton, volleyball, ping pong, and a tennis court were soon eclipsed by Kaplan’s plan to build a swimming pool in March 1944. In 30 days the pool, completed with the generous help of engineers with bulldozer and cement mixer, was the first of its kind in India and the pride of the 803 MAETS. 19

The comforts of home were important to flight nurses assigned to the 830 MAES in the US as well. Although not primitive, quarters on bases where they remained overnight on cross–country flights left much to be desired. In Denver the quarters assigned to the flight nurses in a barracks on the flight line were “pretty terrible”, Dorothy Vancil Morgan recalled – dirty, old paint. So the flight nurses painted the walls, washed the venetian blinds, put up drapes, and talked the Officers Club into giving them some surplus leather chairs that the nurses cleaned up. The result was “beautiful”, she said. The base commander who walked through on an inspection, commented, “I didn’t know we had such a nice-looking building down here!” – and relegated the flight nurses to the nurses’ quarters so that he could use their renovated quarters as VIP quarters. “We felt like throwing mud,” Vancil Morgan said. 20

For more about living conditions of MAES flight nurses, see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II. For more about flight nurses mentioned in this Blog, see Blogs posted for

Ethel Carlson Cerasale 10 Jan 2016 and 16 May 2020

Blanche Solomon Creesy 24 Apr 2016 and 22 Aug 2020

Adele Edmonds Daly 16 Oct 2016 and 20 Feb 2021

Ivalee (Lee) Holtz 30 Aug 2015 and 12 Jan 2020

Alice Krieble 20 Jul 2015 and 1 Dec 2019

Clara Morrey Murphy 10 Oct 2015 and 22 Feb 2020.

Elizabeth Pukas 20 Sep 2015 and 2 Feb 2020

Helena Ilic Tynan 1 Nov 2015 and 14 Mar 2020

Grace Dunnam Wichtendahl for 26 Jun 2015 and 10 Nov 2019.

Audio recordings of my interviews with these flight nurses are available at:

Ethel Cerasale https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011345

Blanche Creesy https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011341

Adele Daley https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011342

Ivalee Holtz https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011350

Clara Murphy https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011353

Elizabeth Pukas https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011355

Helena Tynan https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011359

Notes

- “Initial Installment of Unit History for 816th Medical Air Evauation Transport Squadron”, [30 Nov 1943 – 1 Apr 1944], 4; “816th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron Historical Report June 1945”, 25. [AFHRA MED–816–HI]

- [Winna Foley Tierney], “History of the 806th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron (on the Occasion of Our 25th Anniversary)”, San Antonio, TX, Sep 1968, 2, 4.

- Alice Krieble, interview with author, 3 Apr 1986; Robert R. Smith, “Historical Records 818th Med Air Evac Transport Sq. Cottesmore, Rutland, England Report For Period 1 June 1944 to 30 June 1944”, 2. [AFHRA MED–818–HI]

- Grace Dunnam Wichtendahl, interview with author, 29 Mar 1986; Ethel Carlson Cersale, interview with author, 7 May 1986; Krieble, interview with author.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 September 1944 Squadron History”. [AFHRA MED–819–HI]

- Blanche Solomon Creesy, interview with author, 23 May 1986.

- Clara Morrey Murphy, interview with author, 19 Apr 1986; Clara Morrey Murphy, “Air Evacuation – World War II – African–Europian [sic] Theater”, unpublished speech, 3, 4. [AMEDD].

- Grace H. Stakeman, “807th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron Unit History”, 1943–1944, 24. [AFHRA MED–807–HI]

- Ivalee Holtz, interview with author, 4 Apr 1986.

- Wilbur A. Smith, “Annual Report; January 1, 1943 to December 31, 1943”, 801 MAETS, 31 Dec 1943, 3; Wilbur Anderson Smith, “Historical Narrative of the 801st Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron, Date: May 25, 1942 to June 1, 1944”, 10. [AFHRA MED–801–HI]

- Holtz, interview with author.

- Holtz, interview with author; Helena Ilic Tynan, interview with author, 26 Apr 1986; Adele Edmonds Daly, interview with author, 20 Jun 1986.

- “History of the 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron through January 1944”, 3. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Leopold J. Snyder, “History of 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron for September, 1944”, 31 Oct 1944, 4–5. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Nancy L. Preston and Ada M.S. Endres, “The Feminine Side,” 801 MAES, Aug 1944, 2. [AFHRA MED–801–HI]

- Ibid.

- Dorothy Rice, letter to Lenore Stroop [Leora Stroup], 8 Feb 1944. [AMEDD]

- Elizabeth Pukas, interview with author, 9 Apr 1986.

- “803rd Activities of March 1944”; “803rd Activities for the Month of April 1944”. [AFHRA MED–803–HI]

- Dorothy Vancil Morgan, interview with author, 15 May 1986.