The Twenty–fourth in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

MAETS and the Focus on Europe

Part 3

817 MAETS Activated November 1943

818 MAETS Activated November 1943

819 MAETS Activated November 1943

After arriving at Station #483 Barkston Heath in March 1944, their first assignment in the European Theater of Operations (ETO), the 817 MAETS made its first air evacuation flights, transporting patients from England to Scotland. In June 1944 the squadron participated in only 1 mission into France after D Day to pick up patients for return to England; the flight nurses and enlisted technicians had flown over in 25 planes, but had patients for only 18 of them, for the rest of the patients had been evacuated by hospital ship. The squadron’s 3 other air evac missions of the month were within the United Kingdom.

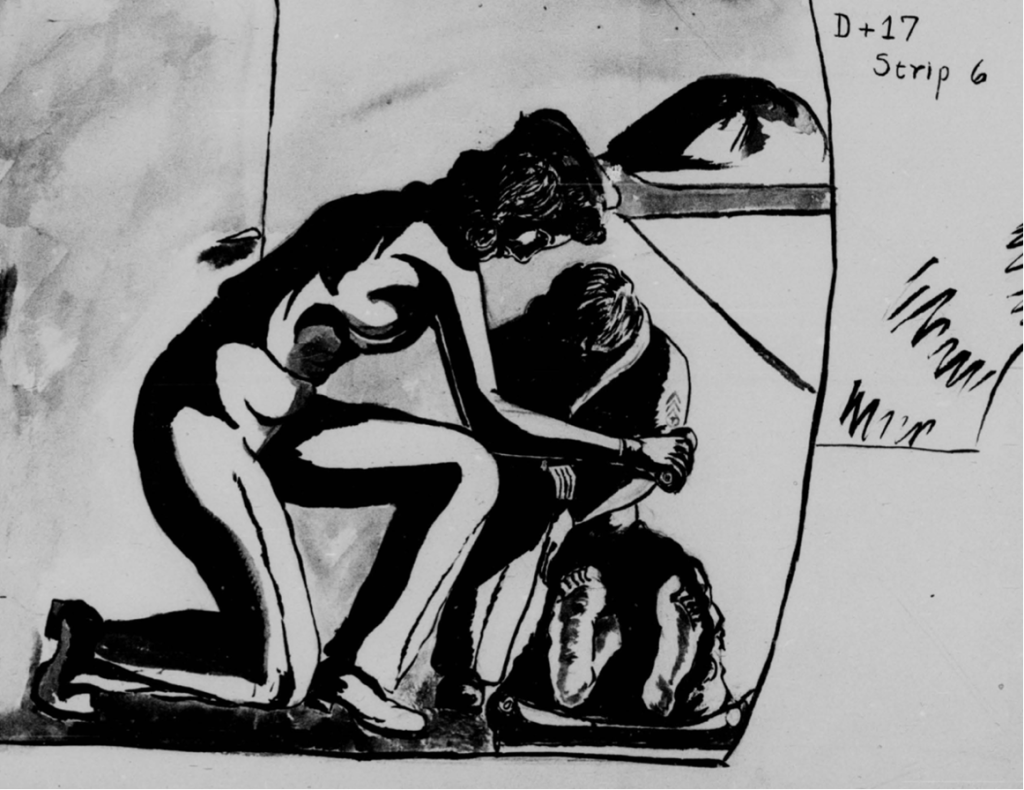

817 MAETS flight into Normandy on 23 June 1944

by T/3 RM Sacks (AFHRA)

In July, 15 of the flight nurse / enlisted technician air evacuation teams were on Temporary Duty with the 816 MAES in Prestwick, Scotland flying with patients on missions to the US; the remaining personnel flew patients from France to England and from England to Scotland. On 27 July flight nurse Catherine Price, who was on detached service with the 816 MAES, was lost along with her enlisted technician and 18 litter patients when the aircraft in which they were traveling was reported missing en route to Newfoundland off the southern tip of Greenland. Alice Fraser, a close friend, wrote “The Lost Mercy Plane” in Price’s memory; 2 of the poem’s 6 stanzas illustrate the tone of the tribute:

One of the stars in our service flag

Has turned from blue to gold;

A nurse’s cap has been laid aside

God has given her a crown to hold.

………………..

And the boys on board that mercy plane,

Had faith in her gentle hand.

But why it had to be Catherine

We may never understand. 1

Air evacuation numbers for July eclipsed those for June. The squadron entered a period of “comparative inactivity” until movement in October 1944 to A–35 Le Mans, France, where the 817 MAES encountered its busiest month since arrival in the ETO. 2 The 817 MAES and 818 MAES worked together at Le Mans until November, when the 817 MAES was transferred to A–41 Dreux. Here on Christmas Day the flight nurses hosted a party for 50 French orphans with food, gifts, and a visit from Pére Noël. 3

The 817 MAES had reason to be proud of one of its own, flight nurse Ann Krueger, for her heroic action on a flight with 27 patients from France to England on 30 December 1944. As was the case with the 807 MAES forced landing in Albania in November 1943, bad weather, radio failure, low fuel, and poor visibility necessitated a crash landing. When informed of the situation, Krueger calmly prepared her anxious patients for the impending impact. After checking their safety belts carefully, she led the men in song. Immediately after the plane crashed, it caught on fire; Krueger quickly evacuated all the patients from the plane, checked them for physical injury and mental stress, and made contact with the nearest hospital where they could be taken. Krueger’s actions earned her the Soldier’s Medal. 4

With the new year of 1945, the 817 MAES personnel were “champing at the bit to be of service to the war effort”, brought on by the German offensive in the Battle of the Bulge. They had their chance when they began evacuating patients from Germany – many of them German POWs in March after the crossing of the Rhine. 5 The squadron participated in air evacuation 24 of the 30 days in April, evacuating almost 15,000 patients, but that record was marred on 13 April when Christine Gasvoda, a flight nurse of the 817 MAES on her way to Germany to pick up patients, was killed in a plane crash in Germany. The sole surviving crew member sought help from a nearby village, but Gasvoda and the plane’s other crew were pronounced dead. 6

After 6 months in Dreux, the 817 MAES moved in May 1945 to Station A–47 Orly where they remained for only 9 weeks. With V–E Day the squadron’s air evacuation missions decreased by about a third, but many patients still needed air transport out of Germany. From Orly the squadron began preparing for their next assignment; news of Japan’s surrender in August changed their plans from redeployment to the Pacific to returning home to the US and eventual deactivation of the 817 MAES. The squadron’s mission had been accomplished in its 2 years of existence, the unit historian noted, but, he added, “Parting is really such sweet sorrow” and their time overseas “had been a lifetime of experiences for all its members”. 7

The 818 MAETS flying personnel were introduced to war in the ETO when after their arrival at Station #493 Spanhoe in April 1944 they, like their colleagues from other squadrons, were sent to bomber bases to observe air operations and treat casualties resulting from missions to the Continent. In May the squadron was placed in charge of air evacuation missions from Northern Ireland to the United Kingdom and transported patients from England to Scotland as well. In June the unit transferred from Spanhoe to Station #489 Cottesmore where better quarters were available for the flight nurses who had been housed in the wing of a hospital at their previous location. The squadron was placed on alert the evening of 5 June in anticipation of D Day, and its personnel made their first trip to France as part of 40 planes flying over on a supply mission on 22 June in which only 12 of the aircraft returned with patients. 8 “Our missions to France have finally gotten us into the swing of real Air Evacuation and our hope is that we will continue to be sent on such missions,” wrote the squadron historian. 9

In the War Diary for June 1944, squadron historian Robert Smith wrote that the flight nurses “felt that had really contributed something by being on the alert crews for the missions on D–Day and D–Day plus one”. Although there was very little to do, they “were doing more than just sitting on the sidelines”. Additionally, those on Detached Service to bomber bases “felt that they learned a great deal about the true hardships those fellows go through”. Again, there was very little work for the flight nurses to do, “but they certainly learned first hand that this war is no child’s play”. 10

July 1944 was fast paced for the squadron with its entire complement of flying personnel sent out on various missions. On 28 August flight nurse Vivianna Cronin was killed shortly after when the plane on which she was traveling as a passenger to Prestwick after a transatlantic air evacuation mission to the US crashed. Bad weather at night caused the pilot to strike a radio tower near Prestwick, the plane burst into flames, and all aboard were killed instantly. 11

Flight nurse Alice Krieble offered a retrospective firsthand account of her squadron’s activities. “We were dumb,” she said of the period preceding D Day. The 818 MAETS had only 1 flight in all this time – to pick up patients in Northern Ireland – and Krieble was on it. Just prior to D Day the flight nurses were farmed out to military hospitals or dispensaries throughout England in what they thought was just procedure – “hurry up and wait”, as Krieble put it. On D Day the nurses were sent back to their squadron’s home base. Krieble remembered her first flight to Omaha Beach after D Day – the planes were allowed only 30 minutes on the ground, because the Germans were still strafing. “They slammed them [patients] at you,” Krieble recalled. 12

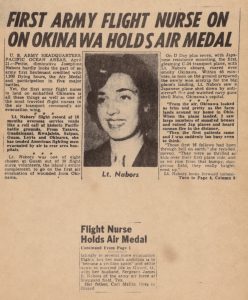

818 MAETS Alice Krieble (2nd from left on 2nd row) and flight nurses,

Bowman Field, KY, March 1944 (USAF Photo)

November 21 and 22, 1944

proved to be the busiest activity yet accomplished by the 818th since arriving in the ETO. Every available nurse and tech was sent out separately on various missions including eight medical techs from the local [Cottesmore] station sick quarters. For a while it looked as though even cooks, baker, clerks, etc., were to become temporary techs, but the aforementioned medical techs took their places. 13

The nurses flew most days, Krieble said, and never more than once a day. After the Battle of the Bulge they flew planeloads of troops into Belgium and brought out patients. At the time of the Battle of the Bulge they put technicians alone on the planes as the only medical attendant flying patients out of Belgium. Krieble remembered that sometimes they would take anyone such as a cook as the medical attendant. The day after Christmas 1944 Alice, along with about 4 other nurses from her squadron, was transferred to Orly Field to fly air evacuation missions from Orly Field to the US on ATC planes. The first leg was from Orly Field to the Azores; the second leg, from the Azores to Newfoundland; and the third leg, from Newfoundland to the US, usually New York, with Presque Isle, Maine as an alternate field. 14

In 1945 the 818 MAES relocated from Cottesmore to Station #385 Le Bourget in France, to A–42 Villacoublay, to Y–34 Metz, and then to A–50 Orleans. February 1945 was the busiest month for the 818 MAES since its arrival in ETO, peaking on Valentine’s Day when 20 flights left their station of Villacoublay, France on air evacuation missions.

The month of February kept all departments ‘on the beem’ [sic], transportation, hauling nurses, surgical technicians to and from the line, clerks, typing out the various reports needed when each extensive evacuation is done. All in all, if repitition [sic] is permitted, the month of February was the busiest for all concerned, and the month of March, with its 31 days, is being looked forward to eagerly in anticipation of succeeding the 7200 total established this month. 15

March did not disappoint, as squadron historian Robert Lee noted:

During the month of March this organization evacuated 14,582 patients. This figure is believed to be the largest ever handled by a single Medical Air Evacuation Squadron in one month. Ten nurses and medical technicians were placed on Detached Service to this unit by the 816th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron to assist in this work. 16

With air evacuation flights declining, 818 MAES personnel were sent on Detached Service or Temporary Duty to other squadrons where their services were needed more. The 818 MAES personnel flew until V–J Day. By August, while still at Orleans, all air evacuation operations had ceased, and the squadron was preparing to return to the US. Krieble remembered that at the end of the war the flight nurses were stationed at Camp Carlisle near Mourmelon in France, a holding point, while awaiting redeployment. This was the time the song “Don’t Fence Me In” came out, which Krieble thought appropriate because of a big fence surrounded the camp. “We thought we were going to Japan,” she said. Instead, when the 818 MAES left Marseille for shipment, its personnel learned that they instead were going to the US. 17

“We of the 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron are well aware of our good fortune in being assigned to what we consider to be the best Air Evac Squadron to leave Bowman Field in the past, present, and future,” wrote squadron historian and flight nurse June Sanders in April 1944. 18 When they reached their first duty assignment overseas at Station #819 Aldermaston in March, the flight nurses and enlisted technicians traveled to bomber bases for 3 weeks of Temporary Duty. Their duties were simple, Sanders reported – be on the flight line for mission departures and returns, attend briefings, treat and accompany casualties to a hospital or dispensary depending on the extent of their injuries. “We learned there is a war going on!” 19

Sanders captured the scene at Aldermaston the month before D Day:

Military momentum is reaching its peak. We can feel it and sense it as new outfits – anti-aircraft, field artillery, airborne infantry – move in. Tents and sealed areas are everywhere. Restrictions have been off again, on again, at a fairly dizzying speed. Something must be cooking soon! 20

In her next report, she shared the scene once D Day had occurred. The squadron personnel watched history being made with the beginning of the invasion and waited for the announcement that air evacuation had begun. “However we did not appreciate the way it came to us – a glamorous picture of girls from a neighboring field [816 MAETS] with their arms filled with poppies – smiling benignly from the front page of the Stars and Stripes [newspaper].” The 819 MAETS finally made its first flight into France on 14 June, and returned to Aldermaston filled with high hopes of at last doing our part in our country’s great enterprise. Fortunately we didn’t then know that we would prove to be – to all appearances – an excess squadron who specialized almost the entire month in being alerted and unalerted. We set new world records in dressing and undressing. … Our month ended with an air of disappointed discontent prevailing [throughout] our squadron, and only a faint hope left with us that we would someday be enabled to at least partake in our primary mission – Air Evacuation. 20

‘It was with no eager anticipation that we of the 819th welcomed the coming of July,” Sanders continued.

Bored, restless, slightly (?) irritable; we settled down to attempt achieving the one apparent attainment left open for us – champion Goldbrickers of the ETO. … But just as we were reconciling ourselves to sleeping till noon, tending to personal matters in the afternoon and keeping up the 434th’s morale of an evening[,] the unexpected occurred. We started working – and we loved it! 21

In July flying personnel of the 817 MAES were sent on Temporary Duty to Lido di Roma, Italy where they worked with the 802 MAES and 807 MAES during Operation Dragoon – the Allied invasion of Provence in southern France to secure vital Mediterranean ports – which later was cancelled. 22

In August 1944, squadron personnel left Lido di Roma and returned to Aldermaston after which flight nurses and enlisted technicians were sent on Temporary Duty with 816 MAETS at Prestwick. They were 1 of 3 MAES assigned at Prestwick to evacuate patients to the US, and consequently their flights on air evacuation missions were about a third of what they had with only 1 squadron assigned. Historian Sanders grumbled,

Our chief responsibility at the present time seems to be proving the practicality of Occupational Therapy as applied to the physically sound. At times this seems to be difficult because social life at this base is not like that at Troop Carrier Stations. Ours for September was comprised principally with a “Knit two, Perl two” circle every evening with both experienced and inexperienced knitters knee deep in yarn. 23

The squadron hoped soon to join the 806 MAES, which preceded them to France. When that had not happened by the end of November, Sanders wrote: “Thirty days has November’ … and THAT was ENOUGH! Our three months sentence with ATC is finally completed – or should be. So far, with the exception of the fact we’re still here with our fingers crossed, we can say our squadron has been lucky.” 24

“Our mail situation continued to stink,” Sanders groused, detailing additional gripes specific to the flight nurses. But when rumors of the nurses’ discontent reached the right person, “All at once we were given a piano, a ping-pong table, drapes, a cocktail party. … Colonel Montague is living up to the wonderful reputation he built up with the nurses at Goosebay [Newfoundland].” She concluded: ‘We have no ouige [Ouija] board to consult, so we know not what lies ahead. Anyone[‘]s guess is good. But please – may we move soon – and together!’ 25

The situation had not improved by December. Sanders waxed poetic when the Christmas holidays arrived and the 819 flying personnel still were at Prestwick:

’Twas the night before Christmas’ in the ETO

Our bedding rolls were packed all ready to go.

We went to church and said prayers sincere

In hopes that our orders soon would be here. J.S. 26

“And so the New Year should find us on the move again,’ a determined Sanders concluded. When that did not happen, chief nurse Phoebe La Munyan wrote:

Christmas is over. – The New Year draws near. –

And from all appearances we still will be here,

We’ve spouted and pouted and fumed and we’ve roared,

The 819th’’s transfer has been well ignored,

Our Mail cannot find us; We’re parked upon shelves,

We surely fell [feel] sorry for – namely – ourselves.

The times in the offing at the close of the year

for New resolutions soon to appear.

We’re firmly convinced we should make a stand,

Size ourselves up and take us in hand:

We will do our best no matter where stuck.

We’ll try not to send our tempers amuck.

We’ll settle us down and all cease to gripe:

But who – inblueblazes – would believe all this tripe: P.H.L. 27

Finally, in February 1945, the 819 MAES was sent to Station #486 Greenham Common in anticipation of a move to the Continent; the flight nurses were scattered from Scotland to the US and points in between at the time of the squadron’s move, which occurred in April when they relocated to A–80 Mourmelon le Grand in France for their busiest month since activation, transporting over 12,000 patients back to England. Squadron morale was high, for “they felt they had done something very concrete toward the war effort”. 28 But by June, with air evacuation activities markedly curtailed, the 819 MAES personnel, like those of other MAES, had turned their thoughts toward home as they began the multi–phased process of returning to the US. Their ship finally arrived in August, and while at sea the 819 MAES learned of the atomic bomb, Japan’s surrender, and the end of the war. 29

For more about flight nurses in the 817 MAES through the 819 MAES see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II. For more about Alice Krieble of the 818 MAES, see Blogs posted for 20 Jul 2015 and 1 Dec 2019. The full text of “The Lost Mercy Plane” is found in the next Blog in this series.

Notes

- Alice Fraser, “The Lost Mercy Plane”, 817 MAES. [AFHRA MED–817–HI]

- Clinton H. McKay, “Unit History June 1944”, 817 MAES, 3 Jul 1944, 3; Clinton H. McKay, “Unit History July 1944”, 817 MAES, 1 Aug 1944, 2; Oscar A. Miron, “Unit History October 1944”, 817 MAES. [AFHRA MED–817–HI]

- “Unit History December 1944”, 817 MAES, 6 Jan 1945, 2.

- Oscar A. Miron, “Award of Soldier’s Medal”, 817 MAES, 9 Jan 1945. [AFHRA MED–817–HI]

- “Unit History January 1945”, 817 MAES, 5 Feb 1945; “Historical Data 817th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron April 1945”, 9 May 1945, 2.

- “Historical Data 817th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron April 1945, 2–3; Joseph L. Boucher, “Statement”, 100th Troop Carrier Squadron, 441st Troop Carrier Group, Office of the Intelligence Officer, Station A–41, 17 Apr 1945. [AFHRA MED–817–HI]

- “Historical Data 817th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron, September 1 – October 13, 1945”.

- “Historical Records 817th Med Air Evac Transport Sq”, 1–30 Jun 1944, 3.

- Robert R. Smith, “Historical Records 818th Med Air Evac Trans Sq.”, 1–30 Jun 1944, 4. [AFHRA MED–818–HI]

- Ibid., 3.

- “Historical Records: Resume,” 818 MAES, 1–30 September 1944, 2.

- Alice Krieble, interview with author, 3 Apr 1986.

- Robert R. Smith, “Historical Records 818th Med Air Evac Transport Sq.”, 1–30 Nov 44, 3.

- Krieble, interview with author.

- John W. Petry, “Historical Records 818 Med Air Evac Sq.”, 1–28 Feb 1945, 8.

- Robert J. Lee, “Historical Records 818 Med Air Evac Sq.”, 1–31 Mar 1945.

- Alice Krieble, interview with author.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 April 1944 Squadron History Initial Issue”. [AFHRA MED–819–HI]

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 May 1944 Squadron History”.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 June 1944 Squadron History”.

- Phoebe H. La Munyan, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 31 July 1944 Squadron History”. [AFHRA MED–819–HI]

- Phoebe La Munyan, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 31 August 1944 Squadron History”.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 September 1944 Squadron History”; Phoebe La Munyan, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 31 October 1944 Squadron History”.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 30 November 1944 Squadron History”.

- Ibid.

- June Sanders, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron 31 December 1944 Squadron History”.

- Ibid.

- Emerson Kunde, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron 30 April 1945 Squadron History”.

- Paul E. Haynes, “Headquarters 819th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron July 1945 – October 1945”.