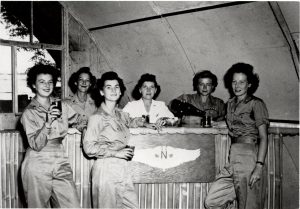

Meet the former US Army flight nurses whom I interviewed for

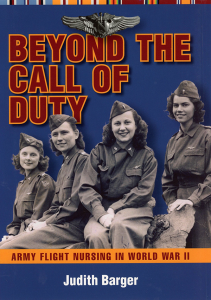

Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II.

In 1986 as part of my research about flight nurse history and coping with war, I was privileged to interview 25 former US Army nurses about events of their flight nurse duty in World War II. Most of them are now deceased, but their stories live on in Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II.

The journal I kept of my time with each of them in 1986 when writing my dissertation offers a brief personal glimpse of these remarkable women. I am sharing edited versions of these journals, in the order in which the interviews took place. The actual interviews are in separate documents.

21st Interview

Jocie Huston

811 MAES Europe

18 June 1986

I met with Jocie in her apartment in San Antonio, Texas this afternoon. She is a tiny woman and small-boned. She had called me two nights before, because she was concerned that she could not find her flight records and therefore wouldn’t know the number of hours she flew, the number of patients she airlifted, and the specific towns and bases into which she flew. She thought perhaps I might not want to interview her after all. On the phone I reassured her that those specific details were not important, and that if she was willing, I would still like to interview her.

Jocie had placed some materials she still had from her flight nurse assignment on a table. But unlike most other women I’ve interviewed, she was not interested or eager for me to look at her photographs. So I did not get the opportunity to see her photo album, other than a few pictures that she pointed out to me.

Jocie’s memory was not too good for many details of her assignment as a flight nurse in World War II. I had realized from our two phone calls that it might not be, so I was prepared. It wasn’t that she was unwilling to share information, but simply that she couldn’t remember the information to share. What she did share was very helpful to the study, and my questions often helped her to remember other areas of her flight nurse experiences. Jocie did remember dates, places, and names, but she didn’t have too much to offer in the way of specific flights or patients.

As a member of the 811 MAES, Jocie was flying patients out of Prestwick, Scotland, usually to Newfoundland, but sometimes all the way to New York, when she heard about D-day. She was eager to get back to southern England from where she would fly across the English Channel to France, but her squadron still had a couple of weeks of duty in Scotland. Jocie did make it over to France not long afterward. She was in the air again on V-J day, on a cargo plane over Germany. Her first stop had no patients to on-load, but the plane diverted to pick up some American and British POWs at a nearby camp for return to England. It was a long day of flying, she said.

My interview with Jocie lasted under an hour. I didn’t want to tax her or make her feel uncomfortable by asking questions for which she might not have an answer. But in the time we did talk, Jocie contributed much important data on coping with war, so it was an afternoon well spent. While not gregarious, Jocie was very friendly and seemed to enjoy my visit to her home.

One of Jocie’s stories: Prior to one of her flights, the flight surgeon told Jocie, “Well, now, this boy’s jaw is wired together, and the weather is going to be bad going back. If he gets sick, you’re going to have to clip these wires.” Her stomach began to churn, because she’d never clipped wires before, and she didn’t know what might happen to the patient’s mouth. She remembered that as a flight nurse she was allowed to give morphine without a doctor’s orders if she thought it was needed. “So I thought, Well, I’ll just give you an eighth of a grain of morphine. I did, and the blessed little fellow slept all the way over, and everybody else on that plane got sick.” Jocie laughed as she recalled the incident.

Jocie died in 1995.