Personal Reflections on Coping with War

Part 3 When Away from Family

For the 25 flight nurses interviewed for Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, wartime service was beset with potentially difficult circumstances that could exact a toll on even the most hardy of nurses. To cope with these professional and personal challenges, these women drew on many sources of support, tangible and intangible, physical and mental. Social support, one’s physical condition, and abilities and skills fostered in nurses’ training all helped the flight nurses cope behaviorally with the multiple demands of the war. Reasonable expectations, devotion to duty, an optimistic outlook, and faith in one’s God, one’s colleagues, and one’s self all helped them cope emotionally with the war.

Social support from squadron and family members was a key element in dealing with the demands of war. Almost two-thirds of the flight nurses interviewed mentioned the importance of esprit de corps and camaraderie in helping them through the war. To four flight nurses it was like a family relationship. What Jenny Boyle, stationed in Europe with the 816 Medical Air Evacuation Squadron (MAES), found helpful was that the people she was with were “like a family.” The other flight nurses often were viewed as sisters. To Randy Rast assigned to the Chine-Burma-India (CBI) Theatre with the 803 MAES, the flight nurses in her squadron “seemed more like sisters to me than my own sisters.” Clara Morrey, initially stationed in North Africa with the 802 MAES, turned down a chance to accompany a patient back to the United States, because she might not have been assigned to her own squadron on her return from the temporary duty.

815 MAES “Sisters” Denny Nagle, Betty Taylor,

815 MAES “Sisters” Denny Nagle, Betty Taylor,

and Ethel Carlson [Author’s Private Collection]

The esprit de corps extended to other members of one’s squadron and to one’s colleagues in flight. Flight nurses praised the work of the medical technicians and emphasized the importance of teamwork in providing patient care. “The rapport between the corpsmen and our flight nurses was magnificent,” said chief nurse Elizabeth Pukas, whose 812 MAES was stationed in Hawaii. “Oh, it’s a team – it was definitely a team,” she added.

The flight crew earned the flight nurses’ respect as part of the air evacuation team. Said Helena Ilic, assigned with the 801 MAES in the Pacific, “The crew chief was invaluable to us. … He helped all of us. It was great.” “Crew chiefs … played a big role in patient care,” remarked Adele Edmonds, also assigned to the 801 MAES, who once was saved from the neck grip of a psychiatric patient by the timely entrance of the crew chief into the cabin of the plane. Frances Sandstrom of the 816 MAES recalled the role of the pilots in Europe: “They were so proud to be doing what they were doing. … were so tickled to be able to do this, that they were so glad to help.”

Good leadership contributed to esprit de corps and fostered teamwork. Rast spoke of an exceptional commanding officer who saw to unit morale. Grace Dunnam, chief nurse of the 806 MAES in Europe, spoke of physicians and commanders who were “right in there with you.” A flight nurse in the Pacific stated, “I think our chief nurse was good for us. She didn’t nag, she didn’t pump, she joined us with our laughter, she joined us with our fun, she didn’t pick. I think that she had something to do with our being content.” Louise Anthony, who flew with the 816 MAES, credited her good assignment in the war at least in part to the quality and fair-mindedness of her chief nurse who the flight nurses knew would always “go to bat right away” for her nurses.

Several flight nurses mentioned the support and pride of family members, who could be relied on to send necessities such as casual clothes and underwear and to provide news from home in the form of letters and newspapers. Even the patients whom the flight nurse evacuated by air were a source of support. Dorothy Vancil, who flew with the 805 MAES in Central Africa, noticed how grateful the patients were for “everything you did for them”; for Morrey, “how appreciative these boys were as bad as they were … for every little thing that you did for them” helped her cope with the war.

You never knew a stranger in the war, Rast remarked. Many flight nurses found that the war had its compensation in the people that they met during their military service. Five of the women interviewed met their husbands during the war. Other flight nurses befriended the natives in an overseas location, saw colleagues from their days of nurses’ training, and met up with relatives.

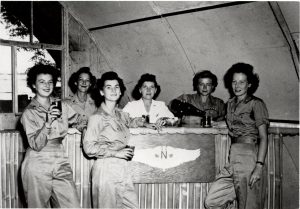

For most of the nurses interviewed, an active social life helped see them through the war. “We worked hard,” remarked Blanche Solomon, who flew with the 822 MAES and later the 830 MAES on the North Atlantic run, “but I think most of us played hard, too, in our free time.” Hosting and attending parties, seeing sights in a foreign country, playing cards in the mess hall, and joining in a songfest – all in the company of friends – provided outlets to help take one’s mind off the war.

Quonset Hut Bar, Clark Air Base, Philippines, 1945

Quonset Hut Bar, Clark Air Base, Philippines, 1945

[USAF Photo]