The Nineteenth in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

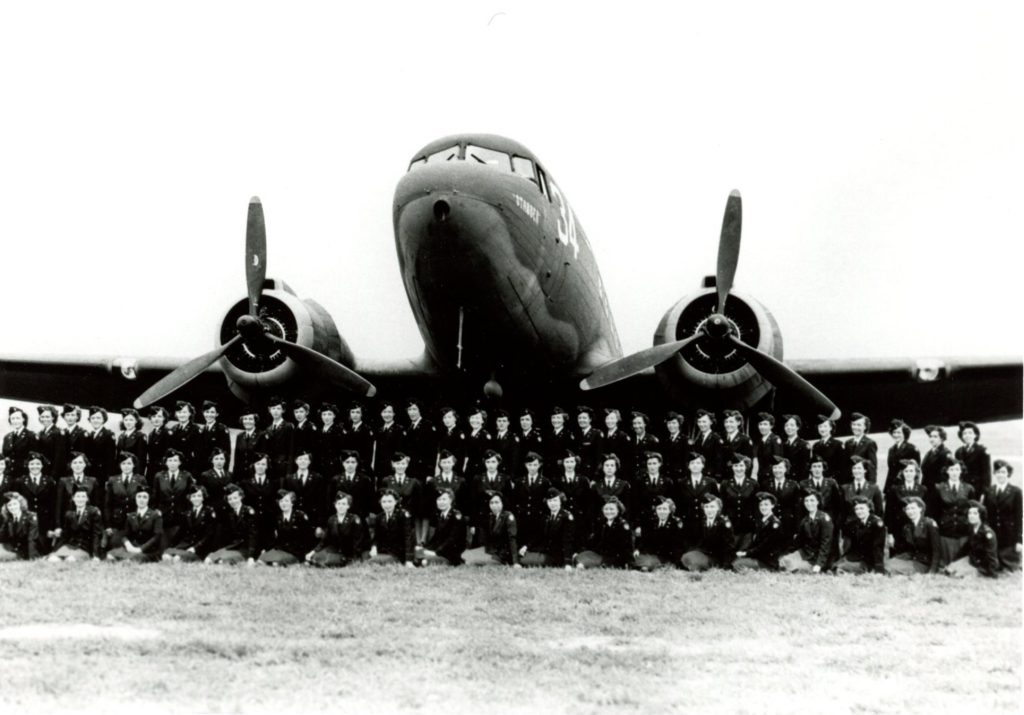

The 808 MAETS and ATC

Activated June 1943

The 808 MAETS was the first air evacuation squadron officially assigned to the ATC, though as was the case with other squadrons, it had flown patients on ATC planes. The Troop Carrier Command provided the planes, mostly C–47s and C–46s, for the bulk of air evacuation in the theaters of operations. The Troop Carrier Command brought patients back from the active fronts to hospitals in the rear areas overseas. The ATC then transported patients to hospitals on the east and west coasts of the US as soon as they could be moved. From there the Ferrying Division distributed patients to convalescent centers throughout the US. 1 For the most part, patients needing evacuation from overseas locations were transported on hospital ships, not by air, early in the war.

808 MAETS flight nurse graduation class, July 1943

(USAF Photo)

In June 1942, AAF General Arnold, who recognized the need for unified military control of air transport, gave the duties of the Ferrying Command to a newly created Air Transport Command. Before the war, as part of the Lend-Lease program, the Ferrying Command employed US airline pilots to transport American-manufactured airplanes – primarily bombers – to the United Kingdom via Canada. As a neutral nation, the US could not fly the planes all the way to the United Kingdom, so Canadian pilots took over and flew them to Scotland. Arnold renamed the Ferrying Command the First Troop Carrier Command to reflect its new mission of training crews and providing combat transport of parachutists and airborne infantry.

In September 1942 Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall directed all theater commanders to call on ATC for the evacuation of seriously wounded soldiers to the US. Although the Army Surgeon General agreed that air evacuation from remote locations such as Alaska would be useful, he did not foresee the need for air evacuation on a massive scale and expected its use, left to the discretion of theater commanders, kept to a minimum. At the time the fledgling ATC had limited global transport capability because of scarcity of aircraft. 2

Before the restructuring, the Ferrying Command already had routes established in the North Atlantic between the US and the United Kingdom, South Atlantic linking the US with West Africa, and South Pacific linking the US with Australia and other islands. The ATC took control of those routes and of the civilian air carriers which were flying military routes overseas. The leadership and pilots of the ATC initially came from airline executives who were recalled to active military service and civilian air crews. New wings were created in October 1942 – the Alaskan Wing, the India-China Wing, and the European Wing in January 1943. The South Pacific Wing became the West Coast Wing, and a new Pacific Wing was formed with headquarters at Hickam Field, Oahu.

By June 1943, ATC was airlifting patients. Although not the primary mission of ATC, air evacuation “was a task at which no one could help but work with enthusiasm”, showing the compassionate side of combat while also serving as an example of military practicality, writes Oliver La Farge, chief historian for ATC during the war. 3 It flew C–47s initially, then added C–87s – the civilian version of the B–24 bomber – and C–46s, and eventually the C–54, a military version of the DC–4, which became the backbone of the ATC fleet. While service was slow getting underway in the European and Pacific Wings, the South Atlantic Wing was “taking off”, and the AAF accordingly assigned the 808 MAETS to the ATC, effective July 1943; Flights A and B had been stationed at Natal, Brazil, and Flights C and D in the Africa-Middle East Wing with station at Accra (now Ghana) since August of that year, but they were not under ATC control. Their duty stations did not change. 4 The teams from Accra accompanied patients from North Africa or Karachi, India to Accra; teams from Natal accompanied patients from Accra to the US. In December 1943, Flight C was transferred to the North African Sector; in June 1944 Flight A joined Flight C in Africa. 5

During 1943 the circuitous route through and from Africa to Florida was necessary because of a lack of Mediterranean bases, shortages of four–engine planes, and the threat of Nazi U-boat action,” writes Robert Futrell. 6 By 1944, additional bases in North Africa and more 4–engine aircraft permitted a more direct route for air evacuation flights. The assignment of the 808 MAETS marked the beginning of organized air evacuation over the South Atlantic route. 7

The South Atlantic route had historical significance as the one taken when Elsie Ott was nurse on the first major test of the evacuation of 5 patients from an overseas location to the US on ATC aircraft in January 1943. On that momentous trip, Ott and her patients had flown from Karachi with stops at

Salala, Arabia (now Oman)

Aden, Arabia (now Yemen) – overnight

Gura, Ethiopia

Khartoum, Sudan

El Fasher, Sudan – overnight

Accra, Ghana

Natal, Brazil – overnight

Belem, Brazil

Borinquen, Puerto Rico

Morrison Field, West Palm Beach, Florida – overnight

Washington DC

Their final destination was Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington, DC.

“Fortunately, or unfortunately depending on how you look at it, I had no nursing to do outside of giving the sum total of four A.P.Cs. [aspirin, phenacetin, caffeine],” wrote Bernice Stick, a flight nurse with the 808 MAETS, to chief nurse Mary Leontine at the School of Air Evacuation, Bowman Field, KY about her ATC flight with 10 ambulatory patients from Natal to Miami in October 1943. “It was a pleasure, however to watch the joy displayed by the boys returning home,” she continued. Stick had thought airsickness would be a problem out of Puerto Rico, the first stop in over 16 hours of flying that offered fresh milk, malts, and Cokes, but the patients were fine. “All in all, I was not much more than a stewardess without the agony of serving meals but it is a beginning. … I’m sure as the trips become more frequent, there will be more to report that will be of more interest,” the flight nurse concluded. 8

The pace of Stick’s work might have picked up when across the world casualties were mounting in the Italian Campaign. Flights A and D of the 808 MAETS relocated to Italy to fly patients from Naples to Casablanca with an intermediate stop in Oran. And in July 1944 the 825 MAES was assigned to the North African Wing to handle the increasing load of patients from Italy and to prepare for increased air evacuation from India. 9 But with the reduction of casualties from Italy, need for air evacuation declined in November, and the Flights of the 808 MAES were reinstated as Flights of the 830 MAES with no change of their current duty locations. 10

For more about Elsie Ott’s historic air evacuation flight from Karachi to the US, see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, Chapter 2.

Notes

- Bob E. Nowland, “Operations of the Ferrying Division of the ATC”, an AAFSAT Air Room Interview by Brigadier General Bob E. Nowland, [1945], 1–2. [AFHRA 248.532–5]

- Robert F. Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation in the USAF, 1909–1960, Historical Studies No. 23 (Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University; Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs / Aerospace Historian, 1960), 167–68.

- Oliver La Farge, The Eagle in the Egg (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949), 229.

- Richard L. Meiling, “Assignment, Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron”, 24 Aug 1943; George E. Leone, “Air Evacuation – South Pacific Wing”, 25 Jan 1944. [AFHRA 141.28T]

- Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation, 366, 368.

- Ibid., 365.

- Ibid.

- J. Bernice Stick, letter to Mary R. Leontine, 18 Oct 1943. [AFHRA 141.28T]

- “History of Flight ‘C’ 825th Med Air Evac Squadron”, 24 Sep 1945. [AFHRA MED–825–HI]

- Futrell, Aeromedical Evacuation, 394–95.