The Fourteenth in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

The 804 MAETS Down Under

Activated December 1942

Unlike their colleagues in the 803 MAETS, the flight nurses of the 804 MAETS did not start to work as soon as they reached their overseas assignment, but rather experienced their own version of the military’s “hurry up and wait”. Graduates of first 2 classes at the School of Air Evacuation, the 803 MAETS flight nurses left Bowman Field, KY with their squadron in May 1943 for the East Coast and boarded the SS Uruguay in New York harbor, passed through the Panama Canal, and disembarked in Brisbane Australia about a month later. Camp Doomben, a former race track, and now a staging area covered with tents, became the squadron’s home for 10 weeks; the flight nurses were detained in Brisbane over 3 months “chafing to go up where their services were needed”. 1 In August 1943 Flight D with 6 flight nurses and enlisted men left Brisbane for Townsville, Australia; the remaining nurses waited in Camp Holland (Brisbane) for the squadron’s arrival in Port Moresby, New Guinea. By October 1943, 12 flight nurses were at Townsville, and the chief nurse and 12 flight nurses had relocated to Port Moresby.

Dorothy Rice’s 2 February 1944 letter from New Guinea to Leora Stroup at the School of Air Evacuation gives a firsthand glimpse of the life of flight nurse in the 804 MAETS. “Air evacuation is still my pet,” she wrote. “Enjoy flying immensely – would fly every day if it were possible, but daily flying would soon wear one out. Still there is much work to be done while one is on the ground.” Rice continues with a description of the dispensary in which the flight nurses provide nursing care, sandwiches, and coffee to transiting air evacuation patients. “Dear goodness what appetites those fellows have. Does your heart good to see them gobbling away.” Among the numerous patients that passed through the dispensary – Australians, Natives, even a Japanese POW – was “a sick little dog. His name didn’t appear on the plane’s manifest so I suppose he would be called a stow-a-way.” 2

Flying time varied from 3 to 9 hours; by the end of the longer flight, “one is fatigued to the point of near exhaustion. Of course, there is always at least one redeeming factor in most every instance of the almost unbearable.” For Rice it was the policy of letting the flight nurse sleep late the next morning, a rare treat. “As 8:00 am rolls around a tray is brought to your room (if so desired and always is). Breakfast in bed! This day is yours”, after which “you are in the old groove again – up at 4:00 am, sometimes earlier than this”. 3

Chief nurse Mary Kerr’s “Nursing Care in Flight”, included in the squadron history and describing duties of the 804 MAETS flight nurses, typifies the standard nursing care provided by other squadrons as well. The flight nurse observed the pulse, respiration, and color of each patient, paying special attention to early post-operative cases. Patients with mental diagnoses also required the flight nurse’s attention; she checked that they were restrained properly and sedated adequately before take-off. Once airborne, the flight nurse administered oxygen to patients with respiratory distress and could insert a rectal tube to relieve distension in patients with abdominal injuries.

Patients with headaches and various minor malaise received aspirin or aspirin with codeine; neo-synephrine nose drops relieved patients with sinus discomfort. The flight nurse attempted to allay nervousness and fear of flying simply by chatting with the patients; a mild sedative might be given if the patient’s anxiety continued. The medical crew made certain that the plane had an adequate supply of blankets, since at high altitudes the patients were likely to feel cold.

Airsickness was a minor problem, Kerr reported, though without quick action on the part of the medical crew, it could become epidemic. The key was to take care of the situation before other patients noticed and reacted themselves. Over time the 804 MAETS evolved a successful treatment for airsickness by placing the individual on a litter or in a reclining position, then administering a sedative and a few breaths of oxygen. 4

Many of the patients that the 804 MAETS flight nurses evacuated had psychiatric diagnoses; care of these patients in flight was particularly important, because disturbances they might cause could affect the safety of other patients and crewmembers. Flight nurses of the 804 MAETS kept clinical data on over 600 patients with mental disorders who were evacuated from Port Moresby to Brisbane over a 4-month period as part of a study to evaluate the methods employed in handling those patients. 5 ATC, which flew these patients from the Pacific back to the US, limited the number of psychotic patients – “locked litters” – on a plane to 5, and the medical crew had to include an additional enlisted technician. 6

Like its neighboring 801 MAETS in the Pacific, the 804 MAETS initially was not under Air Force control, but in this case, under the US Army Services of Supply (USASOS). While the squadron was under the USASOS, its nurses could be based only at Port Moresby and Dobodura – both locations in Papua, New Guinea – which was a matter of no small concern to the squadron flight surgeons, since “This necessitated our substituting Surgical Technicians for Nurses in all evacuation within the combat zone. … For these reasons it was impossible to capitalize on the expert training of our flight nurses where they were most urgently needed.” 7 The 804 MAETS less its nurses finally was assigned to the Fifth Air Force in October 1943; 2 more months passed before the squadron’s flight nurses were placed under the Fifth Air Force as well. The 804 MAETS historian noted the long-awaited event:

December 24th was really a red letter day in addition to being Christmas [E]ve. We received a radiogram stating that our Flight Nurses had been assigned to the Air Force and to the 804th on Dec. 21st. After six months the Squadron was finally all together again and assigned to the Air Force as it had originally been intended to function. The celebration was loud and long. 8

At last under Air Force jurisdiction, the 804 MAETS flight nurses moved with their squadron to Nadzab, New Guinea in March 1944, “happy and excited, prepared to do the work they had wanted for so long. The Flight Nurses were constantly begging to be sent to our most forward installations,” wrote the 804 MAETS historian. 9 When Francis Armin and Josephine Wright flew from Nadzab to Los Negros and returned with plane loads of severely injured men, flight surgeon Leopold Snyder saw them “as they came trudging back to their quarters. Their steps were weary, but their grins were wide and personally I thought I had never seen them look more attractive.” 10

But flying remained dangerous. On 6 March 1944 Lieutenant Gerda Mulack and an enlisted technician were on a routine mission from Nadzab to Saidor in New Guinea to pick up patients for air evacuation. The plane stopped at Finschhafen to on-load cargo and then took off in formation with a number of airplanes. Bad weather intervened, and the pilot’s radio call with the flight leader granting permission to turn back was the last communication with the plane, which was not seen or heard from again. No patients were on board. The crew were declared Missing in Action. 11 A kind letter of condolence that Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Young of the Australian medical corps wrote to the commander of the 804 MAETS revealed the high regard that the Allied troops had for Mulack and her flight nurse colleagues:

It is not too much to say that every Australian soldier, who was carried in a plane manned by one of these nurses, will cherish a memory of their efficiency, and the kindness and careful attention which was characteristic of them. This admiration and respect is heightened by the knowledge of the risks which are accepted daily by these gallant women. 12

That same month flight nurses from the 820 MAETS arrived in Port Moresby from Milne Bay where they had staged since arriving in New Guinea from the US. A day later, unlike was the case for their 804 MAETS flight nurse colleagues, the new nurses started flying – ‘the work for which they had been trained”. With the arrival of the 820 MAETS, and the anticipated policy of returning flight nurses to the US after a year overseas, conversation among the 804 MAETS focused on “When are we going home?” 13

“If matters continue as they have, this history will have to include a special feature “the poetry corner,” flight surgeon Snyder wrote in May 1944. He enclosed 2 “ditties” that the squadron had found enjoyable. In “Christmas Greetings and Farewell”, Janet Foome, chief nurse of the 87th Station Hospital where the 804 MAETS flight nurses had been quartered at Dobodura, wrote that the nurses at her hospital would be sorry to see the flight nurses leave for their next flying duties, but realized that:

The little gold wings you wear o’er your heart

Signify to us that you have a hard part

To do in this job of winning the war

So here’s to you Nurses of the Army Air Corps. 14

“The Troop Carrier Song – New Guinea” by a pilot who had flown with 804 MAETS flight nurses on air evacuation missions speaks for itself:

I’d rather fly a fighter than a transport any day

I’d rather fly a fortress than a biscuit-bomb at Lae

But when I see the Nurses you can bet I’ll always say

I’ll fly the Nurses home.

Chorus

Glory, Glory that’s the way I want to fight

Glory, Glory, that’s the way I want to fight

Glory, Glory that’s the way I want to fight

Just flying the Nurses home. 15

Home remained overseas for the 804 MAES flight nurses who island-hopped with their squadron first to Biak in the Netherlands East Indies off the northern coast of Papua, New Guinea, where the nurses from the 801 MAES, the 804 MAES, and the 820 MAES worked in conjunction, then to Peleliu in the Palau Group southeast of the Philippine Islands, and finally to Leyte in the central Philippines as US troops moved closer to Japan. The original 804 MAES flight nurses returned to the US between January and February 1945 as the squadron awaited their replacements. The new flight nurses moved with the officers and enlisted men to Mindoro in February 1945; here on 12 March the squadron lost 2 personnel – Beatrice Memler and John Hudson – in an aircraft incident when the C–46 with 28 patients on board disappeared in a probable crash due to bad weather. 16 The next day Mary Wiggins and 4 enlisted men flew a patient with acute poliomyelitis from Mindoro to Leyte, where the only known respirator was located, and administered artificial respiration and oxygen throughout the 2–hour flight. The patient arrived at the hospital in good condition. 17

By the end of March, the 804 MAES had moved to Fort Stotsenburg near Clark Field in the Philippines and used those aircraft for its inter-Luzon evacuation. Unit Historian Snyder shared the squadron’s hope that they soon would be headed further north. On its 2–year anniversary overseas, he wrote:

The squadron has come a long way in its two years. It has closely followed every action from Port Moresby to Luzon. It has given nursing care to 75,000 cases, saving a few lives and making thousands of hurt boys more comfortable as they were flown to more adequate hospitalization and needed definitive treatment. All officers, nurses, and enlisted men have a deep sense of accomplishment and a realization that next year will more than ever call for our services. 18

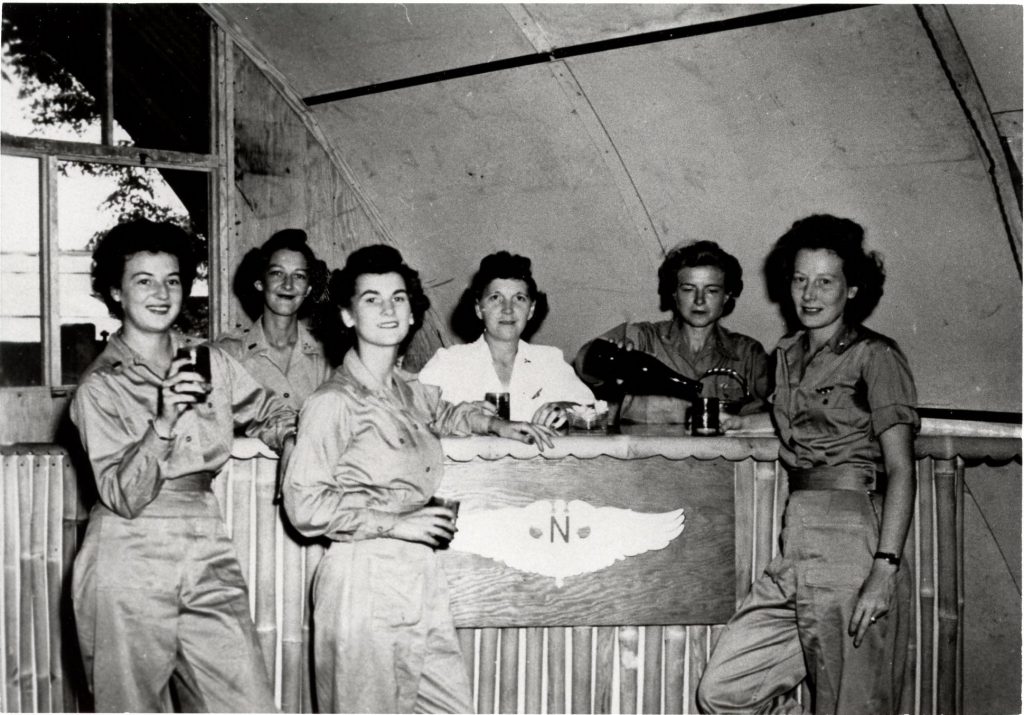

Flight nurses (left to right) Gert Ihrig, Alice Jones, Gwen Matchett (all 804 MAES), Mary Wiggins (801 MAES), Alice Yeagle (804 MAES), and Marion Stemen, Clark Field, 1945 (Author’s Collection)

“We’re off! No we’re not., yes we are!” After many false alerts, word arrived that the 804 MAES was to be operational on Motobu Peninsula, Okinawa by the end of the month; the 820 MAES was already in that location. After the 804 MAES had arrived at their campsite, the Japanese expressed a desire for peace, planes were grounded, and air evacuation was put on hold. The squadron anticipated evacuating American POWs and RAMPs (Recovered Allied Military Personnel) from Japan: “This will be a task we have all worked for and waited for, for the past twenty seven months”. 19

The 804 MAES remained at Motobu evacuating POWs and RAMPs until mid September, when at last they made it to Japan. But after arrival at Tachikawa Airfield, a typhoon suspended all air evacuation flights from Japan to Okinawa, during which time most of the repatriated men were evacuated by hospital ship. 20

For more about the 804 MAES see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, Chapters 2 and 10. To read the entire text of “Christmas Greeting and Farewell” and “The Troop Carrier Song – New Guinea”, see the next Blog in this series.

Notes

- Leopold J. Snyder, “History of the 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron for March 1944”, 12 May 1944. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Dorothy Rice, letter to Lenore Stroop [Leora Stroup], 2 Feb 1944. [AMEDD]

- Ibid.

- Mary L. Kerr, “Nursing Care In Flight”, 804 MAETS, 15 Feb 1944. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- “Air Evacuation of Psychotics in the South West Pacific”, 804 MAES. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Robert F. Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation in the USAF, 1909–1960, Historical Studies No. 23 (Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University; Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs / Aerospace Historian, 1960), 415.

- “History of the 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron through January 1944”, 14. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Ibid., 24.

- Ibid., 27.

- Snyder, “History of the 804th … for March 1944”, 12 May 1944.

- Ibid.

- Gordon Young, letter to 804 MAETS Commander, 24 Jun 1944, enclosure No. 9 in Leopold J. Snyder, “History of 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron for June, 1944”, 12 Jun 1944. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Snyder, “History of the 804th … for March 1944”, 12 May 1944, 5, 8.

- Janet Foome, “Christmas Greetings and Farewell”, enclosure No. 17 in Snyder, “History of the 804th”, 27 May 1944, 44. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- “Troop Carrier Song – New Guinea”, enclosure No. 18 in Leopold J. Snyder, “History of the 804th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadron for April, 1944”, 27 May 1944, 45. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Geoffrey P. Wiedeman, “Casualty Report”, 14 Mar 1945. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Leopold J. Snyder, “March History, 804th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron, APO 74”, 7 Apr 1945, 4. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Leopold J. Snyder, “May History, 804th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron, APO 74”, 2 Jun 1945, 1. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Geoffrey P. WIideman, “August History, 804 Medical Air Evacuation Squadron, APO 337”, 5 Sep 1945, 4. [AFHRA MED–804–HI]

- Futrell, Aeromedical Evacuation, 255.

My mother Kathryn L Beal Feehan was a member of the 804 Air Evacuation Squadron.

She joined the Army Air-Force in November 1941.

She was issued Gilder Pilot’s wings, which she wore throughout her service.

Thank you, Gavin, for visiting my website. I’m always pleased to hear from family members of World War II flight nurses. I was privileged to interview 25 of these remarkable women many years ago, but your mother was not among them, nor did I have the opportunity to interview a flight nurse from the 804th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron. All best, Judy Barger.

Today I was at San Fernando Mission Cemetery San Fernanda, CA and I put a flag for a woman with this name. I looked up her name to find out if I would be able to find anything on her. I’m a USAF Veteran. After I put a flag on her graveside, I saluted and thanked her for her service. I’m thankful.