The Aerial Nurse Corps of America

Part 2

By the 1930s, the use of stewardesses on airlines, an idea launched by Boeing Air Transport, had caught on not only with air passengers but also with America’s nurses who applied by the thousands for the chance to take their nursing into the skies.

Pilot Lauretta Shimmoler, however, had a better idea conceived in reaction to two troubling events she had observed. When at the controls of her new plane en route from Akron to Lorain, Ohio in 1930, she had seen the devastation wrought by a tornado that had swept through that area about a year before, its damage yet to be repaired. What if nurses could have been flown to the scene after the storm to render immediate aid to its victims on the ground and to accompany them by air to medical treatment elsewhere, she wondered. Later when Schimmoler noted the inadequate emergency care provided to a fellow pilot following an accident at an air meet, her idea took more definite form. 1

By 1932 Schimmoler, who now was living in Cleveland where she was vice-president of Vi-Airways and in charge of its Women’s Division, had begun preparations for her civilian flight nurse organization. Here she gathered together a group of nurses interested in her idea and formed the Emergency Flight Corps whose initial task was to research and develop the aerial nurse concept further. After moving to Los Angeles in 1933, where she worked in the first of several aviation-related jobs, Schimmoler continued to pursue her plan for aerial nurses. For the National Air Races held in that city in 1936, Schimmoler provided ten registered nurses to staff two field hospitals under the direction of the Chief Medical Officer for that four-day event. The Emergency Flight Corps, renamed the Aerial Nurse Corps of America (ANCOA), was now operational, having aided 220 persons attending the races. 2 By 1940 ANCOA structure, objectives, routines, and course of study were spelled out in the sixty-three page Regulations Manual and other supporting organizational directives.

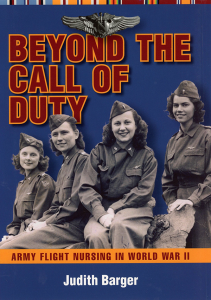

Lauretta Schimmoler (back row far left) and original ANCOA members,

National Air Races, Los Angeles, 1936 [USAF Photo]

In ANCOA literature the point is made that Schimmoler “was fully cognizant that no provisions were being made to provide nurses with the essential aeronautical education”. 3 Whether Schimmoler knew about an existing aerial organization recently formed in New York City in 1931 – the American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc. – is uncertain. Her research, detailed in statements and speeches, identified aerial nurses in France, Chile, and England, but not in her own country. With its purposes to foster and promote air-mindedness in its registered nurse and licensed physician members, to give courses and lectures in aeronautics and allied subjects to qualify members as attendants to patients in air ambulances, and to institute chapters throughout the country leading to a national aviation nursing service, the American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc.’s goals were similar in many respects to those Schimmoler developed for her own organization of aerial nurses. 4 The Journal of Aviation Medicine, a publication of the Aerospace Medical Association, endorsed the New York organization and welcomed news of its progress within its issues for 1931, 1932, and 1933, including in its pages the organization’s founding, constitution and by-laws, reports of meetings, and course of lectures. Only one lecture pertained to care of patients in flight. Other lectures covered the history of aviation and aviation medicine; physical requirements of pilots; the nervous system; the Schneider Test for circulatory efficiency; eyes and ears; effects of altitude, wind, cold, speed, and carbon monoxide; fatigue; airsickness; military and civilian aviation; types of injuries; duties of nurses as flight surgeon assistants, at airports, and as airline hostesses; operation of airlines, airplanes, and aircrews; flying rules and regulations; and demonstration of flight physicals. 5

In 1932 the American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc., suffered the tragic loss of the “American Nurse” airplane, its pilot and co-pilot, and the organization’s director-general Dr. Leon Pisculli in a research flight from New York to Rome in honor of the American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc. 6 Because Pisculli was its primary organizer and backer, the organization lapsed into inactivity after his death. Although the organization was reactivated the next year by decision of its council, news of the American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc. had faded from the pages of the Journal of Aviation Medicine by 1934, about the time that Schimmoler’s aerial organization was attracting media attention elsewhere. 7

From the time that she launched the ANCOA, Schimmoler worked steadily to have the organization endorsed and recognized as the flight nurse unit of various service organizations, both civilian and, ultimately, military. Believing that actions speak louder than words, ANCOA members offered their services at air meets, air shows, and other aviation activities, gaining some local and national exposure in the press. When the need and opportunity arose, the nurses accompanied patients on flights as well. Media coverage that followed had more impact than advertising in bringing the work of ANCOA to the attention of the public. National ANCOA officers then referred to these activities in their speeches to nursing and aviation organizations.

In the late 1930s the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Aero Squadron recognized ANCOA as a voluntary auxiliary unit for emergency and disaster work. 8 In 1938 the National Aeronautics Association endorsed ANCOA as its official nursing organization, and in April 1940 Gill Robb Wilson, the National Aeronautics Association president, wrote to Mary Beard, Director, American Red Cross (ARC) Nursing Service, asking that society to “take a constructive interest” in ANCOA, a “valued affiliate of the National Aeronautic Association”. 9 One must wonder whether Wilson’s letter was intended to reconcile differences between Schimmoler and Beard, since the interest the ARC had shown in ANCOA up to this point had been anything but constructive. Schimmoler recalled Beard telling her, “You have a wonderful idea, but you are ten years ahead of us. If you were only a nurse we could find a place for you.” 10

ANCOA’s association with Relief Wings, Inc., “A Civilian Program to Use AIRPLANES for Humanitarian Purposes in War or Peacetime Disasters at Home and Abroad”, first mobilized in 1940 and for which Schimmoler served on the Advisory Committee for Technical Aeronautical Problems, also was strained at best. 11 Relief Wings planned to establish and maintain as one of its four voluntary corps “Flight Nurses who will not be emotionally or physically disturbed by first air travel, and who therefore can give maximum efficiency under pressure of disaster or air ambulance conditions”. 12 But in 1941 Ruth Nichols, Executive Director of Relief Wings and a licensed pilot, wrote to Harriet Fleming, a member of the California State Nurses Association, ”Although I have felt that Miss Schimmoler has evolved a fine detailed piece of training program for aerial nurses, we have not found any basis upon which she was willing to co-operate with Relief Wings.” 13

Correspondence of Nichols to Schimmoler indicates that Nichols thought they had an agreement that Schimmoler was not honoring. In short, Nichols would help ANCOA obtain more members if those members would be available for disaster service under Relief Wings, but Schimmoler apparently was not encouraging this collaboration. At stake was each woman’s control over the limited number of nurses available for civilian aerial work during time of war and her claim to the uniqueness of that work. 14 Whether their differences ever were reconciled is not known, but Nichols’s letter to Fleming in 1942 suggests that Relief Wings did not know the present status of ANCOA; Nichols had heard, however, that it “had died a natural death”. 15

ANCOA had not died, but the ultimate association that Schimmoler sought for her organization – to form a unit of the United States military – was beyond her control. ANCOA had as one of its purposes

to provide technically trained and physically qualified personnel to fulfill the requirements of the Medical Department of the U. S. Army and Navy Nurse Corps, under their supervision, in national emergencies, for nursing duty in air transports, at airports and air bases of the Army, Navy and Marine Corps in time of national and civic emergencies. 16

Schimmoler, who founded her flight nurse organization independent of the other service organizations such as the United States Army and the ARC, nevertheless intended that ANCOA would become the air unit of the ARC, which in turn provided nurses for the military. Undaunted in the face of the skepticism she encountered when promoting her new organization to nursing officials, Schimmoler relentlessly pursued her goals. The formative years of flight nursing prior to the development of the program in the United States Army Air Forces were marked by the rivalry of these two organizations – ANCOA and ARC – that were in contention to provide the nurses for a flight nurse program in the United States military. This rivalry highlights an issue that has plagued nursing from its beginning: that nurses should control their own profession.

To be continued

Notes

1 Aerial Nurse Corps of America, Regulations Manual (Los Angeles, Burbank, CA: Schimmoler, 1940), n.p.; Leora B. Stroup, “A New Service in an Old Cause,” Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 105 (Sep 1940): 186.

2 Aerial Nurse Corps, Regulations Manual, n.p.; Douglas J. Bintliff, “Aerial Nurse Corps,” Air Trails, Nov 1940, 54; Emerson, “Most Recent Emergency Unit,” 10; Stroup, “New Service,” 186–87.

3 “The Aerial Nurse Corps of America” brochure, n.d.

4 “The American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc.,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 2 (1931): 262–63.

5 Ibid.; “The Nurse in Aviation,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 3 (1932): 5; “The Nurse in Aviation,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 3 (1932): 116–18.

6 “The American Nurses Aviation Service Inc.,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 3(3) (Sep 1932): 176.

7 “American Nurses Aviation Service, Inc.,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 4 (Mar 1933): 19.

8 Emerson, “Most Recent Emergency Unit,” 10; Leora B. Stroup, “What is the Aerial Nurse Corps of America?” n.d., 2; James Farrer, “Flying Nurses Do Without Glamor,” [Dayton] Sunday Mirror, 20 Apr 1941; “Nurses Mobilize for Duties in New Home Defense Service,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Mar 1941.

9 Gill Robb Wilson, letter to Mary Beard, 16 Apr 1940.

10 Lauretta M. Schimmoler, letter to H.A. Coleman, 22 Mar 1945; Lauretta M. Schimmoler, “The Story of How It All Began: “And They Said It Wouldn’t Be Done,” unpublished manuscript, n.d., 7.

11 “Relief Wings,” brochure, n.d.

12 “Relief Wings, Inc.,” Journal of Aviation Medicine 12 (Sep 1941): 260.

13 Ruth Nichols, letter to Harriet Fleming, 16 Feb 1942.

14 Ruth Nichols, letter to Lauretta Schimmoler, 5 Dec 1941.

15 Nichols, letter to Fleming, 16 Feb 1942.

16 Aerial Nurse Corps, Regulations Manual, 1.