“Fate dealt us another unlucky blow”

Part 2

When CPT Grace Stakeman, Chief Nurse and Unit Historian for the 807 Medical Air Evacuation Squadron [MAES] in Catania, Sicily, penned these words for 30 January 1944, she was referring to a jeep accident that had injured three of her flight nurses early that morning, one of whom died in hospital hours later. The events of and following that accident are described in Part 1 of this Blog. The other unlucky blow had occurred in November 1943 when thirteen of her flight nurses and twelve enlisted technicians – half of the squadron’s flight teams – had found themselves in German-occupied Albania after the plane on which they were traveling to air evacuation stations in Italy got off course in poor weather and force-landed in German-occupied Albania. This Blog describes the Albanian “unlucky blow” from entries in war diaries and other 807 MAES documents written by squadron personnel who remained in Catania, Sicily, and from an interview with one of the nurses in Catania. The experiences of the personnel downed in Albania, all of whom survived, is told by Agnes Jensen Mangerich, one of the flight nurses, in Albanian Escape: The True Story of U.S. Army Nurses Behind Enemy Lines and in Chapter 6 of Judith Barger, Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II.

The 807 MAES arrived in Catania on 6 October 1943 to start their air evacuation duties. Part of the squadron was detached to Grottaglie, Italy on 19 October 1943 to organize air evacuation activities from that station; another part of the squadron was detached to Bari, Italy on 25 October 1943 for the same purpose. The squadron history for November notes that

On 8 November, 13 Nurses and 12 Enlisted Men were being flown from Catania, Sicily, to the stations at Bari and Grottaglia [Grottaglie], Italy. For several days preceding this date, weather had prevented getting any attendants forward, and both advanced stations had been without personnel for several days. For this reason, a large number were being sent to both of the advanced stations.

“It was thought that it was going to be just another trip where they would all be coming back with yarns about this city or that one and with souvenirs that they would sell for what they paid, just to give us fellows who had to stay behind something that we would never be able to get,” the history stated. Thus the 807 MAES personnel in Catania could not understand why the flight surgeons at the destination stops – Captain Philip Voigt at Bari and Captain Edward Phillips at Grottaglie – sent radiograms that same day asking for attendants, since the flight nurses and technicians should have arrived at each station by the time that the radiograms were sent. The squadron history continues:

Immediately the office sent out a reply stating that they had left at 8:30 that morning and should be there and for them to be on the lookout for their arrival. No word came and we thought the plane had arrived but when a message came back contrary to our thoughts we began to get worried.

The personnel on Catania knew only that Plane # 68809, a C-47 of the 61st Troop Carrier Squadron of the 314the Troop Carrier Group in which the squadron personnel were passengers, had “failed to reach either of its destinations.”

Major William P. MacKnight, the 807 MAES commander, spent the next two days “looking over the country side” with no success, and by the fourth night after the plane had left Catania, the squadron had still received no word about the safety of its passengers. When on 13 November word came that the plane might possibly have landed in Greece, the squadron still hoped for their safe return, and on 14 November Captain Simpson flew to Italy to continue the search but returned with a negative report on 16 November. While he was away, letters to the families of the missing personnel were typed, and signed by Major MacKnight on 15 November, and on 16 November request was made for replacements for the missing personnel.

Planes continued to look “high and low” over the Adriatic Sea and enemy territory, and pilots taking off from Catania who were acquainted with the missing flight nurses continued to search on every flight. Given this diligence in searching, squadron personnel held out hope that they would receive good news soon; when news arrived that the plane might have made a landing in Yugoslavia or Albania, hope was renewed for the safe return of all the plane’s occupants. By 19 November, “things begin to look doubtful, but all hope was not lost.” Two days later, “After a thorough search, the plane’s occupants were declared officially ‘missing’ and dropped from the roles of the 807 MAES.”

807 MAES Personnel Declared Missing in Action

| Nurses | Enlisted Technicians |

| 2LT Gertrude G. Dawson | T/3 Lawrence O. Abbott |

| 2LT Agnes A. Jensen | T/3 Charles J. Adams |

| 2LT Pauleen J. Kanable | T/3 Paul G. Allen |

| 2LT Ann E. Kopsco | T/3 Robert A. Cranson |

| 2LT Wilma D. Lytle | T/3 James P. Cruise |

| 2LT Ava A. Maness | T/3 Raymond E. Ebers |

| 2LT Ann Markowitz | T/3 William J. Eldridge |

| 2LT Frances Nelson | T/3 Harold L. Hayes |

| 2LT Helen Porter | T/3 Gordon M. Mackinon |

| 2LT Eugenie H. Rutkowski | T/3 Robert E. Owen |

| 2LT Elna Schwant | T/3 John P. Wolf |

| 2LT Lillian J. Tacina | T/3 Charles F. Zeiber |

| 2LT Lois E. Watson |

“Credit must be given to the remaining Nurses and attendants for their determination to carry on despite all odds,” the historian wrote. As the days stretched out, the flight teams in Catania were doing their best to fill the gap left by their missing colleagues, but the squadron was “operating on a skeleton basis now.” The 17 November entry stated that “patients are being evacuated just as fast as ever but the lost comrades are really needed. Nurses and technicians alike are going out as fast as they come in to get another load.”

In an interview in 1986, Dorothy White, one of the flight nurses who remained in Catania, recalled the months that her squadron colleagues were missing in action.

But those of us that were left behind – there was thirteen on that plane, so that left twelve of us back at the base – we did not know where they were. In fact, it was almost a week before we were actually told that they were missing. Then it was just a missing report, no idea where they were. And it was a month after they were gone before we were finally told where they were. And we did not give any hope for when they might come back.

When asked what it was like for the squadron members who were not among the thirteen in Albania but were the ones that were left in Catania in relative safety to carry on the air evacuation work, White replied:

It was a very lonely time. Every place you looked, you saw empty chairs, empty cots – the emptiness. Because with only twelve left, we were doing all the work. So if you did come home for a day, it was long enough to get your clothes cleaned, and you would take off again. But that meant the others were gone. So instead of having twenty-five around and half of them working at a time, you were down to twelve working, and might be two or three of us … So the worst thing for us to do was to go to the mess hall, because you had nothing but empty chairs. We would eat at one little – we had a couple of big, long tables. We’d all get over at this one little table in the corner and eat there, because you at least were close to somebody.

The first month – November – was the most difficult for the squadron personnel in Catania, because they “didn’t know anything.” By December the squadron knew that their missing colleagues were alive and were “on their way back to allied hands,” but “didn’t know when we would see them again.”

White continues:

So, we just looked – many times standing on the coast of the Adriatic Sea, and you’d look across, and you knew they were over there someplace. And it was like you were willing them to come home and making a bridge – a little air bridge sort of like a rainbow – so that they could climb over. But it was a very bad time for us, but we still worked so hard during that time. The work, of course, helped us to get through it. But in the back of your mind, you always knew – you just kind of had this tight feeling between your shoulder blades – that, Where are they? How are they? How are they surviving? Is everybody all right?

In early December the squadron learned that the missing personnel had crash-landed in Albania, and that they likely could escape the Germans if absolute secrecy was kept of their whereabouts. “This wonderful news brought the squadron morale from the depths to an absolute high. Everyone prayed for a grand reunion at Xmas which did not materialize.” The first of the replacements arrived on 31 December from Florida by plane with news that the others – who arrived on 3 January – were on their way, just weeks before the missing flight nurses and technicians returned to the 807 MAES.

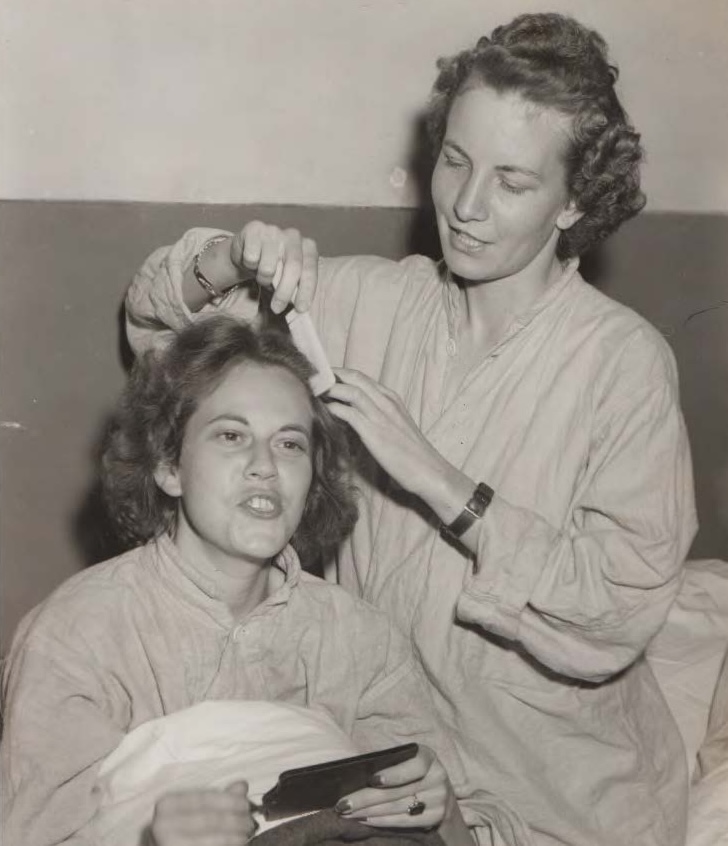

On 14 January eight of the flight nurses and all but two of the technicians arrived back in Catania after brief hospitalizations in Italy. “They all look a little thin,” the historian commented, “but it is hoped that this will soon be overcome by a little nourishment.” LT Jensen, who had developed a boil on leg, T/3 Cruise, who had pneumonia, and T/3 Zeiber, whose illness was not disclosed in the squadron history, required longer hospitalizations and remained behind in Italy. Zeiber returned to the squadron on 18 January, Cruise on 21 January, and Jensen on 24 January, On 15 November LT Lytle, LT Maness, and LT Porter had become separated from their colleagues in the confusion of an anticipated German attack in the village where the group was staying and were still declared missing.

Agnes Jensen (right) and flight nurse colleague at 26th General Hospital, Bari, Italy

after return from Albania [USAF Photo]

Flight nurse White exuberantly picks up the story of her colleagues who had returned:

It was fantastic that day. We were eating lunch, and Teach [CPT Stakeman], our chief nurse – the phone rang. Well, this was in Sicily, and she said in a loud voice – and I remember thinking it unusual at the time – she called the mess sergeant to the door, because we were eating lunch, and she called him, and she said, “Sergeant Brock,” she says, “we will have thirteen guests for lunch.” And everyone stopped. Forks were in mid-air. And then we finally stopped, and we looked at each other. That number thirteen gives me chills to this day. And then nobody could eat any more from then. We didn’t know what to do, we were all so eager and excited. Pretty soon we could hear some jeep horns honking, and here they came in, in the jeeps, and I remember just standing there looking at them. I couldn’t believe it. There was my roommate for a whole year and a half walking up, “Hi, Whitey. What’s for lunch?” Just like as nonchalant as could be.

Stakeman adds:

Our joy for those returning was only shadowed by the fact that three of our nurses were still in enemy territory – Lts. Lytle, Maness and Porter. Security was all important at this time. The escapees were impressed deeply with the need for closed lips so the next two weeks were joyous but slightly difficult. Those just returned from such an experience were bursting to tell their story and we who had waited so long, about to explode, holding questions back.

The squadron historian explained why the escapees couldn’t talk about their experiences – “serious trouble could have come of relating their story at this time” because of the three nurses still in enemy territory. Also, “since other planes are forced down in the same country,” loose lips could “give away valuable information to the enemy.”

From the little that the returnees could say, the squadron learned that “they had done considerable walking by the appearance of their shoes.” The aircraft had been burned to give the enemy the idea that all had perished in the crash. Water was plentiful and good, but food was scarce and poor, obtained mainly through thieving and bartering. Diarrhea, jaundice, and lice plagued them throughout the forty-nine days.

Flight nurses of 807 MAES on return from Albania, January 1944 [USAF Photo]

After two weeks, the returnees received orders to return to the States, and on 26 January nine flight nurses and eleven technicians boarded a plane for Algiers to begin their journey home. Lytle, Maness, and Porter were still missing, and others of the group were hospitalized and would return home at a later date. “There was a large gathering to witness the takeoff and bid them, the lucky ones, good-bye.”

The unlucky ones, LT Lytle, LT Maness, and LT Porter, finally returned to Catania from Italy on 27 March 1944 after having arrived in Allied territory on 22 March – over four months after what was to have been a routine day of flying. “Each one looks as though she were on a vacation,” the squadron historian remarked, “but it was felt that they are glad to be back in our midsts [sp] again.” Their ordeal had not required as much walking but was no less taxing for the difficulties encountered trying to arrange return to their squadron. Like the rest of the group downed in Albania, the three flight nurses departed Catania by plane, shortly after their arrival, homeward bound on 29 March 1944.

Audio recordings my interviews with Dorothy White Errair and with Agnes Jensen Mangerich are available at:

Dorothy Errair: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011347

Agnes Managerich: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011352

Notes

Facts and sequence of events surrounding the accidents are gleaned from the following sources:

Errair, Dorothy White. Interview with Judith Barger, Cocoa Beach, FL, 24 May 1986.

Mangerich, Agnes Jensen. Interview with Judith Barger, Cocoa Beach, FL, 25 May 1986.

Stakeman, Grace H. “807th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron Unit History.” (Inactivated 11 Dec 1945). In File MED–807 –HI, 1942–Dec 1945. [AFHRA]

“War Diary for November 1943,” 807 MAES. In File MED–807–HI. [AFHRA]

“War Diary for December 1943,” 807 MAES. In File MED–807–HI. [AFHRA]

“War Diary for January 1944,” 807 MAES. In File MED–807–HI. [AFHRA]

“War Diary for February 1944,” 4 Mar 1944, 807 MAES. In File MED–807–HI. [AFHRA]

“War Diary for March 1944,” 3 Apr 1944, 807 MAES. In File MED – 807 – HI, MAR 1944. [AFHRA]

For Further Reading

Barger, Judith. Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II. Kent State University Press, 2013.

Mangerich, Agnes Jensen. Albanian Escape: The True Story of U.S. Army Nurses Behind Enemy Lines. As told to Evelyn M. Monahan and Rosemary L. Neidel. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.