The Eighteenth in a series of Blogs about the 31 Medical Air Evacuation

Transport Squadrons activated during WW2

to provide inflight nursing care to sick and wounded soldiers,

tended by Army flight nurses and enlisted technicians.

The focus is on the flight nurses.

From Sicily to Italy with the 807 MAETS

Activated May 1943

Beginning with the 807 MAETS, newly activated squadrons were sent to areas overseas where intensification of the war required additional air evacuation activity to transport wounded soldiers out of the combat zones. In August 1943 the 807 MAETS departed Bowman Field, KY for the Mediterranean, where the 802 MAETS had been assigned since February of that year.

807 MAETS Bobbie Ruminski and Jean Rutkowski in bivouac photo op,

Bowman Field, KY, 1943 (USAF Photo)

In September the 807 MAETS arrived in Tunisia where they worked with the veteran 802 MAETS for a few weeks before departing for their first home base at Catania, Sicily. Allied soldiers had begun fighting in the Italian campaign that same month when the British military invaded the toe of Italy, after which the Italian government surrendered to the Allies, and American soldiers landed at Salerno. Naples was liberated after 4 weeks of fighting. By November 1943, flight nurses and enlisted technicians of the 807 MAETS were going out as fast as they came in to get another load of patients for air evacuation. 1

In early November 1943, about half of the 807 MAETS flight nurses and enlisted technicians – one of the latter from the 802 MAETS – were on their way from Catania on Detached Service to newly opened air evacuation stations at Bari and Grottaglia, Italy, but after the air crew encountered bad weather, radio issues, enemy action, and low fuel, the pilot was forced to crash land in an unknown location that turned out to be enemy–occupied Albania. The plane’s occupants were met by friendly partisans but told that Germans were in the surrounding areas, so the air and medical crews, only one of whom was injured on impact, had to make their way stealthily – mostly on foot – with the help of Albanian partisans, British Special Operations officers, and an American intelligence officer, to reach an Allied base on the coast. Their journey took 2 months for most and 4 months for the 3 flight nurses who were separated from the larger group along the way. The missing personnel eventually made it back to Italy for hospitalization and debriefing in Bari before rejoining their squadron in Catania.

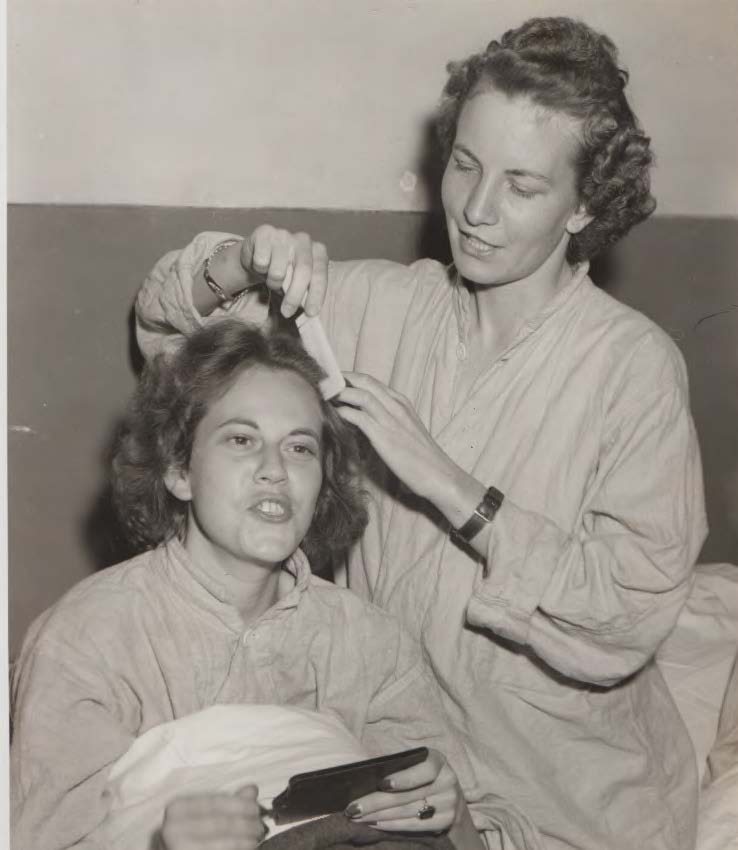

807 MAETS Agnes Jensen (right) and colleague at 26th General Hospital, Bari, Italy

after return from Albania (USAF Photo)

While the missing flight nurses and enlisted technicians were making their way out of Albania, the squadron members in Sicily were operating with only half of their allotted number until replacements arrived just 10 days before the missing personnel returned.

Dorothy White was among the flight nurses left behind in relative safety in Catania. She remembered it as a very busy time, since 12 flight nurses were doing the work of 25 and a “very lonely time. Every place you looked you saw empty chairs, empty cots, the emptiness.” The worst place was the mess hall, where no one would eat at the long tables. “We’d all get over at this one little table in the corner and eat there, because at least you were close to somebody.” 2

Dorothy White (right) in bivouac photo op,

Bowman Field, KY, 1943 (USAF Photo)

White Errair recalled the “fantastic” moment the squadron’s missing colleagues returned. When at lunch in their mess hall, the phone rang, and chief nurse Grace Stakeman answered it. “Sergeant Brock,” she called to the mess sergeant in a loud voice, “We will have 13 guests for lunch.” White continues the story:

And everyone stopped. Forks were in midair, and then we finally stopped, and we looked at each other. That number thirteen gives me chills to this day. And then nobody could eat anymore from then. We didn’t know what to do, we were all so eager and excited. Pretty soon we could hear some jeep horns honking, and here they came in, in the jeeps, and I remember just standing there looking at them. I couldn’t believe it! There was my roommate for a whole year and a half, walking up, “Hi, Whitey, what’s for lunch?” Just like as nonchalant as could be. 3

807 MAETS flight nurses after return from Albania

(USAF Photo)

Allied forces landing near Anzio in January 1944 found their way to Rome blocked by German forces that encircled the beachhead. Unable to make any headway against the enemy, Allied troops “were locked in a bloody stalemate” lasting 5 months. 4 They finally broke out and fought their way north to Rome, which they liberated 2 days before the D-Day invasion of Normandy. Grace Stakeman, the 807 MAETS chief nurse, recalled air evacuation trips that her flight nurses made while the squadron was stationed in Catania as a time when they had the satisfaction of doing the work for which they had been trained. 5

For 1 flight nurse of the 807 MAES, a trip from Anzio – 1 of her first with American patients – made a lasting impression. All her patients had been wounded within the previous 24 hours, and 3 of them, all amputees, were straight from the operating room.

Two boys that had been through the Sicilian and Italian invasions together. They had stepped on mines and both had lost both feet. These two were directly opposite each other on the plane and were very cheerful – at least they were together still. One boy was shot through the neck and had a tracheotomy tube inserted, along with fractured legs, arms, and many shrapnel wounds.

The trip was, in the flight nurse’s words, a nightmare – and these were only a small number of almost 1,000 patients evacuated that day. “Our boys can really take it,” the flight nurse concluded. “Not one complaint of pain or remorse on the trip.” 6

The 807 MAES, which had evacuated patients to Naples but had not relocated there because of the rapid progression of Allied fighting, moved instead further north that November to Lido di Roma, which the 802 MAES had once called home. 7 During the Italian campaign they operated on the eastern side of Italy evacuating primarily British patients, while their sister 802 MAETS transported Fifth Army American soldiers from the western Italian coast. 8

Misfortune struck the 807 MAETS again at the end of January 1944 when a jeep in which flight nurses Mildred Wallace, Mary Allen, and Dorothy Booth were riding overturned. Wallace suffered a skull fracture and died shortly after the accident; Allen dislocated her shoulder. Booth, who suffered facial and head lacerations and fractured teeth and vertebrae, required air evacuation to a hospital in Algiers, but the plane on which she was traveling on 24 February 1944 crashed near Caltagirone, Sicily, killing all on board, including Elizabeth Howren, the flight nurse for the mission. 9

During the summer of 1944 the 807 MAETS was at its busiest, and additional detachments opened to meet air evacuation needs as the army moved forward. The squadron flew the patients to Naples, a trip of about an hour, and the air evacuation teams often made 5 trips in 1 day, transporting as many as 100 patients. Since so many of the soldiers were encased in plaster, “sometimes almost from head to foot,” the plane passageway at times resembled “a hopscotch court.” 10 The 819 MAES from England arrived in July 1944 to help the 802 MAES and 807 MAES during Operation Dragoon – the Allied invasion of Provence in southern France to secure vital Mediterranean ports – which later was cancelled. 11

In July alone, the 807 MAES evacuated over 13,000 patients – a record for them – bringing the squadron total to over 37,000 patients. 12 Flight nurse Edith Baldwin was struck by the positive spirit of the wounded patients, exemplified by one particular soldier she evacuated during the Italian campaign: “He was the ‘smilingest’ boy of the 18 litter patients on the airplane as I climbed aboard, and he was apparently eager for this, his first plane ride. Having heard stories of things that go on at the places where these boys have been wounded, I wondered how it was possible for any of them to have anything that even resembled a cheerful look.” The grinning patient, who spoke broken English, offered to help Baldwin as she tried to decipher diagnoses from medical tags written in French. Her smiling patient, she learned, had lost a leg in battle. “It was not easy to turn and face him with a smile that could match his own. How do they do it? I wonder.” 13

The need for air evacuation in the Mediterranean decreased considerably in 1945, and after V–E. Day in May 1945, personnel in the 807 MAES and 802 MAES started switching places. Those with high points in the 807 MAES giving them priority for shipment home were transferred to the 802 MAETS, while those with low points in the 802 MAES were transferred to the 807 MAES anticipating shipment of that squadron to the Pacific. 14 V–J Day caused a welcome change in plans, and 2 years after their arrival overseas, the entire squadron was now homeward bound.

For more about the 807 MAES and about the personnel’s time behind enemy lines in Albania, see Beyond the Call of Duty: Army Flight Nursing in World War II, Chapters 5 and 6. Agnes Jensen Mangerich, one of the flight nurses on board the plane, has written her own account of the journey in Albanian Escape: The True Story of U.S. Army Nurses Behind Enemy Lines (University Press of Kentucky, 1999). For more about flight nurses in the 807 MAES, see Blogs posted for

Dorothy White Errair 4 Jul 2016 and 24 Oct 2020

Agnes Jensen Mangerich 24 Jul 2016 and 14 Nov 2020

Audio recordings of these my interviews with these flight nurses are available at:

Dorothy Errair: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011347

Agnes Managerich: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80011352

Notes

- “Report of Air Evacuation Activities for Period of Sept 4 to Dec 1 [1943]”, 807 MAES. [AFHRA MED–807–HI]

- Dorothy White Errair, interview with author, 24 May 1986.

- Ibid.

- Evelyn Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee, And If I Perish: Frontline U.S. Army Nurses in World War II (New York: Knopf, 2003), 277.

- “Report of Air Evacuation Activities for Period of Sept 4 to Dec 1 [1943]”, 807 MAES.

- “Stories We think Worth Mentioning, 807th Med Air Evac Transportation, Year 1944, The Italian Campaign”, 2. [AFHRA MED–807–HI]

- Grace H. Stakeman, “807th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron Unit History”, 1943–1944, 24. [AFHRA MED–807–HI]

- Robert F. Futrell, Development of Aeromedical Evacuation in the USAF, 1909–1960, Historical Studies No. 23 (Maxwell AFB, AL: USAF Historical Division, Research Studies Institute, Air University; Manhattan, KS: Military Affairs / Aerospace Historian, 1960), 188.

- Stakeman, “807th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron History”, 18–19.

- Ibid., 23.

- Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 25–26.

- Edith Balden, “Spirit of the Wounded”, in “Stories We Think Worth Mentioning”, 807 MAES, 1.

- Stakeman, “807th (US) Medical Air Evacuation Squadron History”, 42–43.